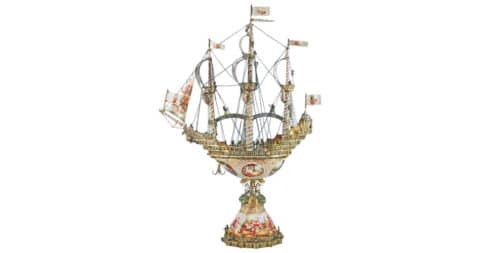

April 3, 2017London antiques gallery A. Pash & Sons specializes in 19th-century silver from sought-after makers in England and France. Top: A detail, right of the 1860 trophy made by Elkington & Co. that Queen Victoria presented to the racers of the Royal Mersey Yacht Club.

London’s South Audley Street in Mayfair has long enjoyed a reputation as a premier destination for fine antiques. Despite recent incursions by fashion boutiques, the street is still home to an impressive roster of top dealers, and when it comes to silver, none shines quite as brightly as A. Pash & Sons.

The company was established in less salubrious surroundings, in London’s West End, in the 1920s by Wolf Pash. The current, third-generation proprietor, Robert Pash — Wolf’s grandson — learned about silver at an early age from his father, Arnold, whose initial still holds pride of place above the door. Early on in his tenure, Robert recognized that there was an opportunity to narrow the gallery’s focus to the top echelon of 19th-century silver production. And under his leadership, A. Pash & Sons has become the preeminent dealer in antique silver and objets d’art.

Integral to the running of the business is gallery manager James Raymond, whose remit encompasses such diverse responsibilities as managing the firm’s website, conducting detailed academic research and cataloguing. He came to Pash as a 16-year-old in need of a summer job. Robert challenged him to clean every silver item in the shop, and although his summer break ended before he got through the entire inventory, the task instilled in him a lifelong love of silver. Raymond returned to the business following his graduation from college, some 20 years ago, and has since handled pieces ranging from Elizabethan to Art Deco, with particular expertise in the 19th century.

Today, the Audley Street premises are filled with the best examples from that high point of opulent design and craftsmanship. Raymond recently led Introspective through a glittering array of table centerpieces, candelabra, flatware and equestrian and sporting trophies, all the while explaining their history and contemporary appeal.

An 1877 Victorian sterling silver set in Richard Martin and Ebenezer Hall‘s Venetian pattern includes settings for 12, plus tea service, all in a wooden canteen-style box.

What aspect of nineteenth-century silver does A. Pash & Sons focus on?

We tend to go for the top five percent of the nineteenth-century canon. That, generally speaking, is English and French, and there were some half dozen really top makers: Garrard, Barnard, Elkington & Co. and Hunt & Roskell, in London and Birmingham; and in Paris, Odiot and Christofle, among several others. Today the pieces that are most sought after remain those that are incomparable. Centerpieces with important provenance, whose makers originally created them to impress, have the same effect on buyers today.

How does nineteenth-century silver differ from that of earlier periods?

The nineteenth century is all about modern manufacturing techniques and the industrialization of the silversmith’s craft. In the eighteenth century, silver was mostly made in small workshops, but the subsequent century saw the age of the industrial artisan. Many craftsmen in great workshops made more ambitious works for a fast-paced market.

It is impossible to define the aesthetic of nineteenth-century silver. It is simply too broad. In England, for example, pieces from 1800 or 1810 are much the same as those from forty or so years before: reserved in design, utilitarian in nature. What followed from 1810 to about 1830 helped to shape the whole Victorian period, with the “neo-” styles becoming prevalent: Neoclassicism, neo-Rococo, neo-Baroque and neo-Romanticism all had their moment in the following decades. Chinoiserie and the arabesque also come to the fore, as well-traveled Victorians wanted their homes to reflect their international experiences.

Originally opened in West London, the gallery now occupies a window-fronted space on South Audley Street, in the city’s Mayfair district. Gallery manager James Raymond, seen here, first came to work for the dealer when he was just 16, at which time he primarily served as the silver polisher.

Raymond describes the Birth of Aphrodite, ca. 1900, as “a masterpiece in silver and enamel by Alexander Fisher.”

Who were these ornate pieces of silver made for?

Silver makers in the nineteenth century had fantastic patrons, with the Prince Regent, later King George IV, setting the fashion. There was a love affair between the aristocracy and silver, and the Illustrated London News from 1840 to about 1880 would regularly show pieces commissioned by aristocrats or royalty — the celebrities of the day.

It made silver hugely aspirational, and as the nineteenth century drew to a close, silver makers targeted the middle-class market. The pinnacle was from the Regency to 1910, and we handle the best examples from that period.

How does this ornate silver work in a more contemporary interior?

We have clients from around the world: Russia, China, Ukraine and the Middle East, but also Europe, particularly Britain, France and Belgium. It is a wide demographic, but generally speaking it comprises people who appreciate great things and have large residences that can accommodate pieces such as ours.

There are so many nineteenth-century silver styles, and we encourage our clients to have an eclectic mix. Buy what you like, not something you think you should have. We’ve always been willing to bring pieces to clients’ homes — in the shop sometimes you can’t see the forest for the trees, and you may find you love a piece when you see it in more familiar surroundings. Generally, buyers want to enrich their interiors, and when they put an amazingly decorative object in a relatively plain space, it sings.

Do people still use this kind of silver?

Absolutely. It’s what these items were made for. We’ve got pieces that have been used extensively for the past two hundred years but show few signs of wear. They are fantastic works of art and functional objects.

François Joubert, the lead designer for top French silver maker Odiot, made this candelabra and centerpiece garniture for the 1878 International Exhibition in Paris.

Does silver require a great deal of looking after?

It’s best to keep on top of it — the longer you leave an object untouched the more you need to clean it. With the more elaborate pieces, some clients have them professionally treated, so then you don’t have to polish them at all. It is completely reversible and does not harm the silver.

How significant are hallmarks to assuring silver is authentic?

Collectors of vintage silver, and particularly English silver, are protected because of the hallmarking system. To forge a hallmark is a criminal offense, like forging a bank note. There are handbooks for identifying hallmarks, which show who made a piece and where and, of course, that a piece is solid silver. Electroplating [bonding a thin layer of silver or gold to another metal, usually nickel in English silver and bronze in French] was patented in England in the 1840s and, as it results in pieces that are not solid silver, these bear a maker’s mark, not a hallmark.

Is collecting silver only for the very wealthy?

For a few hundred pounds, you can buy a piece by an excellent maker from the Victorian period whose greatest works will cost six or seven figures. A fantastic way in is to pick a master such as Garrard or Barnard. You will find that even their salt cellars or cruet sets will be better quality than pieces by their lesser competitors.

TALKING POINTS

James Raymond shares his thoughts on a few choice pieces from A. Pash & Sons.