June 12, 2017A new exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art celebrates the 150th birthday of Frank Lloyd Wright and the institution’s acquisition of the great 20th-century architect’s archive, including this 1956 drawing of Chicago’s never-realized mile-high Illinois skyscraper. The show is just one of the myriad ways the world is marking Wright’s sesquicentennial. Top: The designer at work (Photographer unknown). Artwork courtesy of The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives, unless otherwise noted

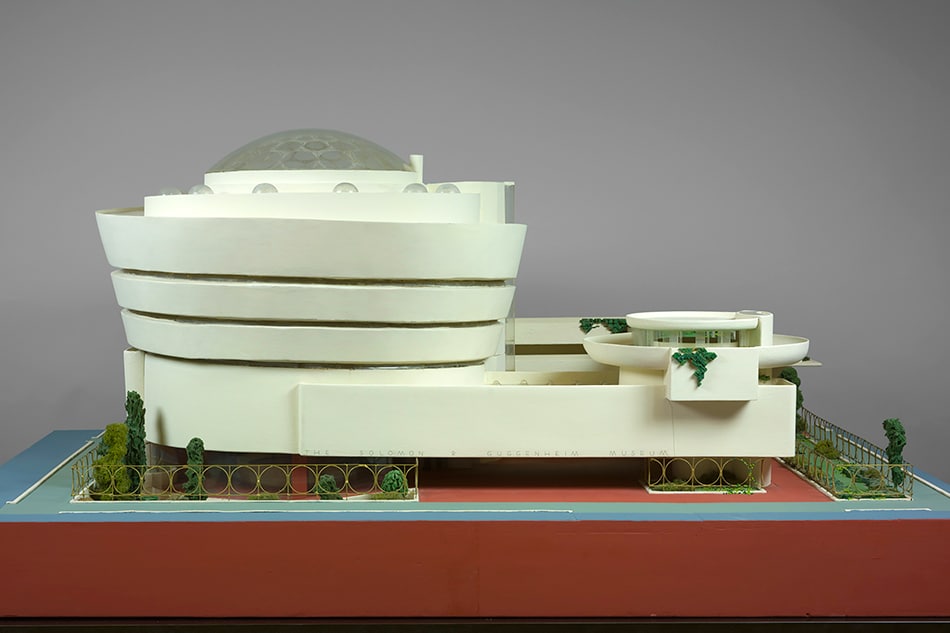

Frank Lloyd Wright liked nothing more than to be relevant. The man Philip Johnson once dismissively called “the greatest architect of the 19th century” was likely the greatest architect of the 20th. Named Time’s “Man of the Year” in 1938, Wright worked feverishly until his death, in 1959. He was 91, and one of his most influential buildings, the spiral-shaped Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, was just about to open.

Now, Wright is exerting his influence in the 21st century. Born in 1867, just after the Civil War, he would have been 150 on June 8. Institutions like New York’s Museum of Modern Art and companies like Schumacher are marking the sesquicentennial, in both cases with the help of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, which owns and operates Wright’s two studios: Taliesin, in Spring Green, Wisconsin, and Taliesin West, in Scottsdale, Arizona. In 2012, the foundation sold the vast Wright archives — consisting of 23,000 architectural drawings and 44,000 photographs, plus models, manuscripts, and other documents — to a pair of New York institutions: MoMA and Columbia University’s Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library.

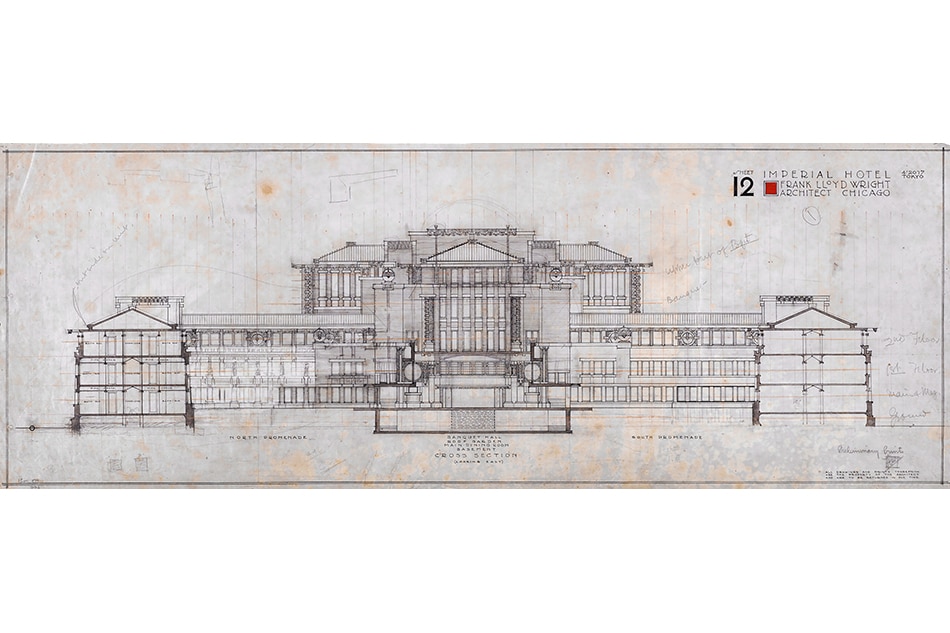

Barry Bergdoll, a renowned architectural historian with longstanding connections to both instituti0ns, and a dozen guest curators spent five years combing through the trove, choosing 450 works, many of them never before exhibited. “The archive is filled with surprises,” says Bergdoll, citing Wright’s designs for a model school for African-American children and a rare Japanese photo book of the Imperial Hotel, Wright’s Tokyo masterwork, with the architect’s own sketches in the margins.

The result is MoMA’s exhibition “Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive,” which opens today and runs through October 1. It explores the gestation of such projects as Unity Temple, the Unitarian Universalist church built in Oak Park, Illinois, between 1905 and 1908; the Robie House, in Chicago, constructed from 1908 to 1910; Fallingwater, completed in 1937 in southwestern Pennsylvania; and the Johnson Wax Administration Building, erected from 1936 to 1939, in Racine, Wisconsin. Off the “spine” of the exhibition, 12 satellite galleries examine themes running through Wright’s career, such as his engagement with Native American imagery in his quest to create a truly American architecture.

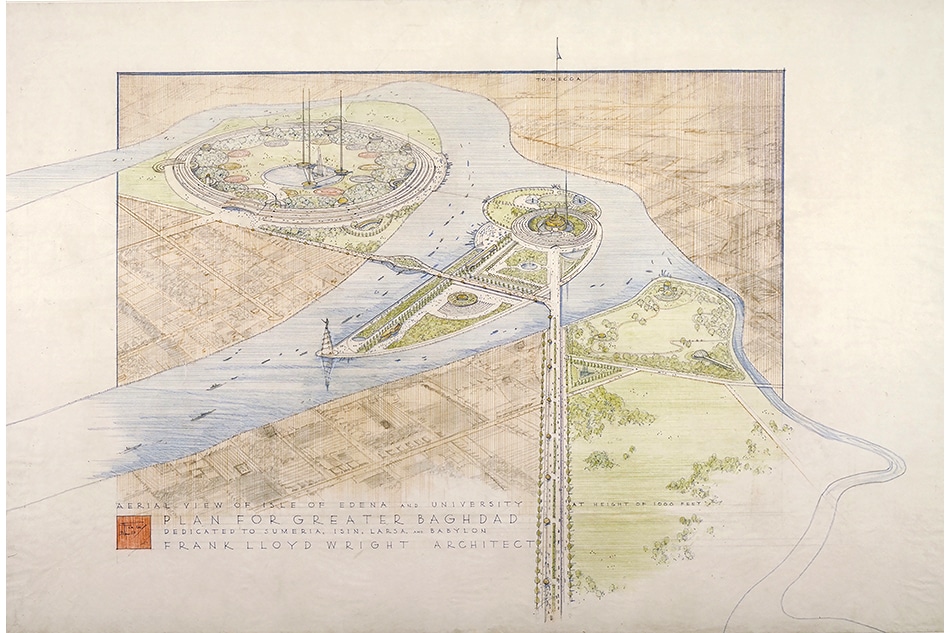

The show includes “spectacular things that will stun,” says Bergdoll, giving as examples Wright’s very large-scale drawings for a mile-high skyscraper and for a new district of Baghdad. There are also films of the guest curators unpacking the archive. “It’s a little bit like Antiques Roadshow,” jokes Bergdoll, adding, “You are watching active historical interpretation.

Ken Oshima, an architectural historian at the University of Washington, was one of the guest curators. “Wright,” he says, “was certainly one of the first global architects, with an equally expansive imagination, so I believe he would take pride in being considered current today.”

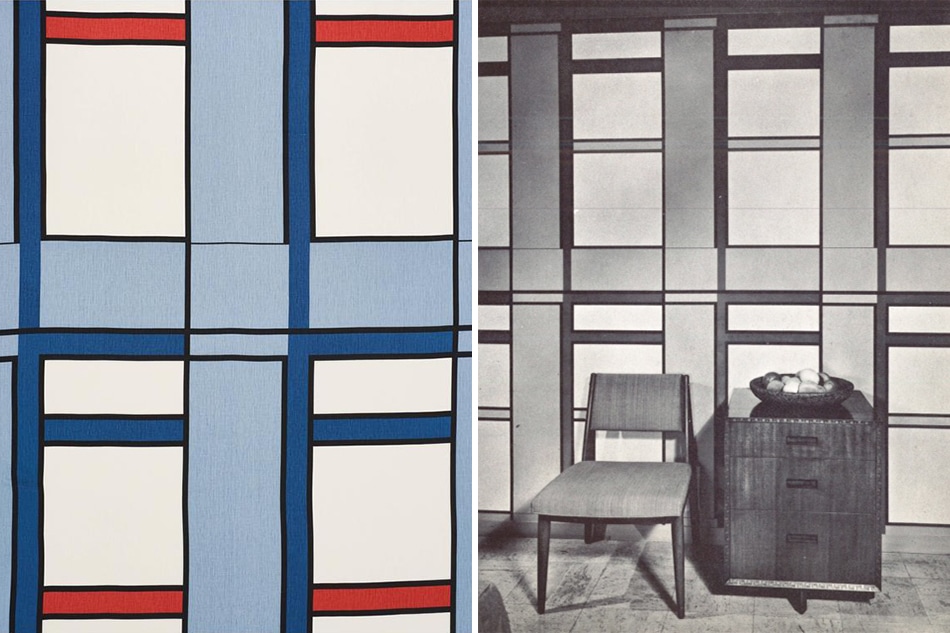

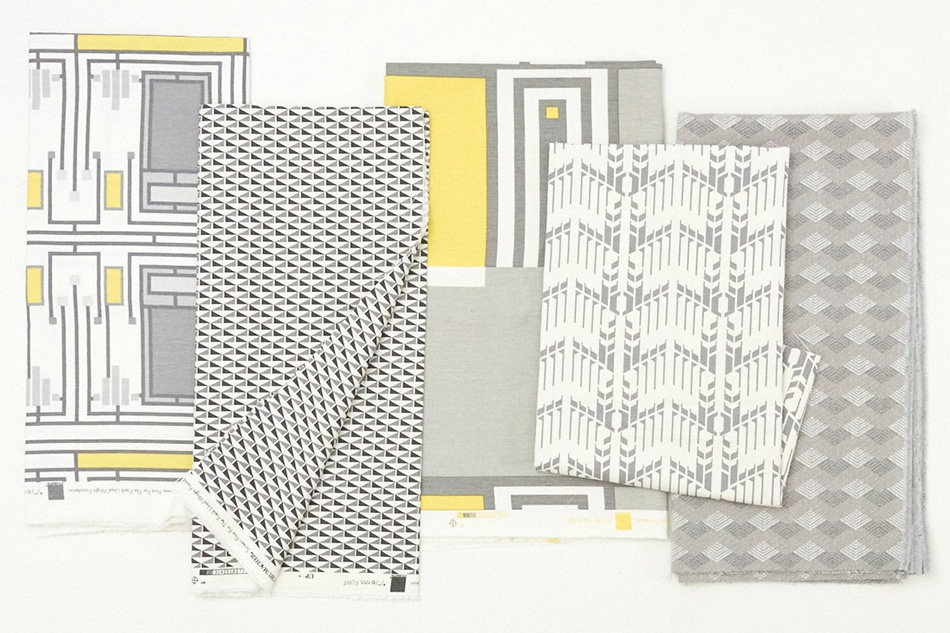

Private enterprise is also using the birthday as a peg. Even after it sold the archive to MoMA and Columbia, the foundation retained the copyrights for Wright’s designs. It has licensed some of them to Schumacher, the family-owned fabric company founded in 1889. In 1955, the firm launched a collection of Wright fabrics, officially called “Schumacher’s Taliesin Line of Decorative Fabrics and Wallpapers Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.” Now it is releasing a new line of 12 prints, some designed by Wright, including six that were included in the 1955 collection, and others derived from his sketches and drawings. They include the Francis Little Sheer, based on a drawing for the Francis Little House, which was built beside Lake Minnetonka in Wayzata, Minnesota, between 1913 and 1920 and torn down by the Little family in the 1970s (its living room was re-created at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art). The Schumacher collection also contains the St. Mark’s Print, based on a sketch by the architect of the never-built St. Mark’s-in-the-Bouwerie residential tower, in New York City’s Greenwich Village. (A painstakingly reconstructed model of the tower is included in the MoMA show.) Other patterns are derived from designs for the Imperial Hotel, which was demolished in 1968.

For his 150th birthday, Schumacher has released a dozen Wright and Wright-inspired designs, including six that are reissues from a collection of fabrics and wallpapers the architect created for the company in 1955. Schumacher is currently offering pillows in several of these prints on 1stdibs. Photo courtesy of Schumacher

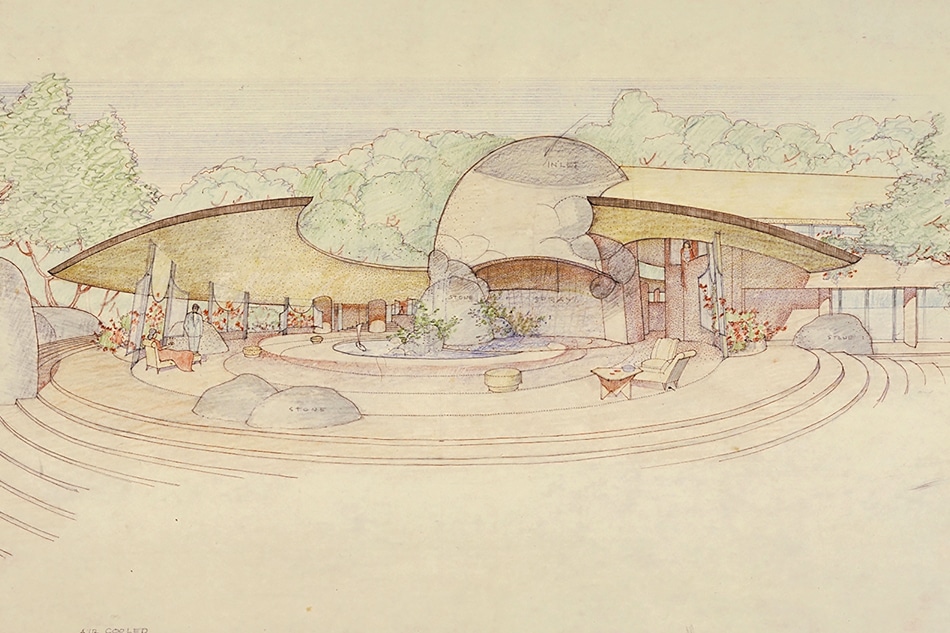

For those who can’t ever get enough of Wright, half a dozen of his houses are currently for sale. They start at $365,000 for the Jackson House (1956), built from prefabricated parts in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin, and $510,000 for the Weisblat House (1948), in Galesburg, Michigan. At the high end, at $8 million, is Tirranna (also known as the Rayward-Shepherd House, 1955), a sprawling horseshoe-shaped spread in pricey New Canaan, Connecticut, with floors in Wright’s favored Cherokee Red and a rotating observatory above the master bedroom.

More typical of the Wright buildings for sale is the 2,600-square-foot Olfelt House (1958), in Minneapolis. Owned by Paul and Helen Olfelt, who commissioned it from Wright as newlyweds, it is one of just five of the architect’s houses still in original hands — at least for now. Priced at $1,395,000, it comes with Wright-designed furniture and lighting and a rare-for-Wright finished basement.

Historians frown on separating Wright’s pieces from the residences for which they were designed. Indeed, the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy was founded back in the 1980s, when some Wright tables and chairs were worth more than the houses that contained them, leading to some houses being stripped. The conservancy has worked to match sellers with buyers who are interested in keeping the houses intact — and it has had remarkable success. It also helps when sellers, like the Olfelts, are patient. Selling a Wright house sometimes takes years.

Of the items that have made it to market, a number are on 1stdibs, including a pair of outdoor light fixtures, offered by Architectural Artifacts, originally from the Francis Little House, and a secretary’s chair from Wright’s Price Tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma — now an arts center and hotel — acquired by Mod50s Modern directly from a member of the Price family. Also among 1stdibs finds are pieces designed by Wright for mass production, like his Taliesin dresser, offered by dealers Flavor and Mix, from his 1950s collaboration with the North Carolina–based furniture company Henredon.

The man Philip Johnson once dismissively called “the greatest architect of the 19th century” was likely the greatest architect of the 20th.

Thanks to his prolific contributions to the built environment — from Prairie style houses to New York’s landmark Guggenheim Museum — Frank Lloyd Wright is as iconic as the American landscape itself. He’s seen here in an undated photograph taken in the Arizona desert. Photographer Unknown

The sesquicentennial is being celebrated as far away as Tokyo, where the current iteration of the Imperial Hotel — which opened in 1970 and was not created by Wright — has unveiled a lounge designed around artifacts from the older building, including Wright-designed furniture and tableware. Taliesin is showcasing photographs of the architect and his buildings by Pedro Guerrero, a Wright intimate who died in 2012. And the architect’s native state of Wisconsin is unveiling a 200-mile-long Frank Lloyd Wright Trail, with Wright-inspired signage pointing to nine sites. Another organization, the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust, is sponsoring such events as an online exhibition of his photos from his 1905 visit to Japan. And if you’d like to stay over in a Wright building, the Emil Bach House (1915), in Chicago, can be rented for short-term stays, with a $150 per night discount in honor of the anniversary.

Frank Lloyd Wright left another kind of legacy: seven children, dozens of grandchildren and innumerable great-grandchildren. Among the great-grandchildren is Catherine Ingraham, an architectural historian who teaches at Harvard. Of her great-grandfather, Ingraham says, “It would be presumptuous to comment on how he might feel about his contemporary relevance. However, my guess is that he would not be surprised.”