November 13, 2022You’ve probably never heard of French architect Hervé Baley. Neither had the New York–based dealer Hugues Magen — until 2019, when he was contacted by Clément Cividino, who runs a design gallery in Perpignan, in the south of France.

“He told me he had something to show me,” says Magen. It turned out to be a handful of furniture pieces designed by Baley between the 1960s and early ’90s. “I was like, ‘What is this?’ ” recalls Magen. “They were all fantastic on their own and even more so as a whole. And I didn’t know about this guy!”

Magen has since made up for lost time. He has acquired more than a hundred Baley pieces, some 40 of which are being presented in a new show at his Magen H Gallery, on East 11th Street in Manhattan, that runs until December 23. To coincide with the exhibition, he is publishing the first monograph ever devoted to the architect’s furniture creations, titled simply Hervé Baley.

Baley’s creations are at once simple and complex. Partly because of financial constraints, he favored humble materials like pine and plywood. Aesthetically, he adopted sharp, angular forms that were cleverly juxtaposed and interlocked in an origami-like fashion. There are stools whose diagonal legs slot neatly together, a sofa with a high back that could almost have been made for a church and a wall-mounted writing desk that looks as if it had been fitted with wooden wings.

With amusement, Magen recounts how he disassembled a small side table made from half a dozen triangular and trapezoidal pieces of wood to pack it flat for transportation. “My crew took hours to put it back together,” he says. “They almost went nuts.” It was part of a small selection of Baley pieces that he presented in June at Art Basel, where the reception was wildly enthusiastic. “People went crazy,” says Magen. “People who love Prouvé and Perriand find a resonance with Baley’s forms. Items have already made it into some big collections.”

Even in France, interest in Baley (who died in 2010) is extremely recent. “He was totally marginal, a sort of anomaly in the history of French architecture,” says Anne-Laure Sol, a curator at Paris’s Musée Carnavalet who, in her former role as heritage conservator for the Greater Paris region, edited a 2018 book devoted to Baley’s buildings as well as those of his peer Dominique Zimbacca.

Baley’s father worked for a shipping company, and the future architect spent much of his childhood abroad. He was born in Gabon in 1933 and later moved to Brazil and Morocco. From 1951 to 1954, he studied at the School of Fine Arts in Paris, most notably under Georges-Henri Pingusson, who is best known for some exquisite Art Deco residential buildings, as well as the Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation, near Notre-Dame in Paris.

The architect who had the greatest impact on Baley, however, was the American Frank Lloyd Wright, whose work he discovered through an exhibition in the French capital in April 1952. Eleven years later, he embarked on a two-month study trip to the States during which he visited dozens of Wright buildings, including Taliesin East. “For him, Wright was a Bach, a Mozart, a Vivaldi, a Beethoven of architecture,” notes Jean-Pierre Campredon, a friend and student of Baley’s. “Hervé was drawn to his quest for oneness.”

Baley was vehemently opposed to the modernist movement, accusing Le Corbusier’s famous Cités Radieuses (a series of utopian postwar apartment blocks) of being “indifferent to the environment, inhuman.” Instead, he advocated that architecture should be “organic,” founded on creating a symbiosis between a building’s inhabitants and their surroundings.

Although Baley designed a gas station, a clinic and shopping mall restaurants, his output was largely limited to housing in and around Paris, often for clients with limited means. His private homes were generally centered on monumental fireplaces and featured free-flowing floor plans, large windows, overhanging rooflines and facades with block patterns. Whenever possible, he conceived custom furniture to fit snugly within the intricate architecture. The pieces eschewed rectilinear orthodoxy for a sometimes dizzying array of diagonal and angular forms. Bizarrely, while the furniture is almost spellbindingly proportioned, the buildings themselves could be contrived and clunky.

Baley’s success was limited, and a lack of commissions in France led him to decamp to Morocco in the ’90s. It didn’t, however, lead him to make many concessions. “He didn’t compromise with his conception of architecture,” notes Sol. “He had a very personal vision, which he championed right to the end.”

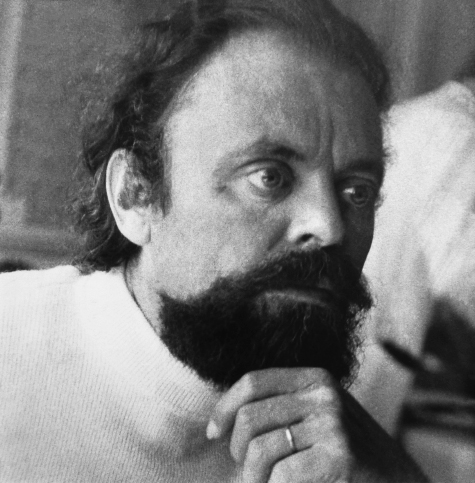

He also transmitted it to a number of disciples. Over 22 years, Baley trained some 115 architects of several nationalities as a teacher at Paris’s École Spéciale d’Architecture (his classes included physical exercises and automatic writing). He was short in stature but powerful in personality and had an almost prophet-like persona. “He could be warm and friendly but didn’t allow real complicity,” says Campredon. “There was something more priestlike about him.”

The furniture that Magen has so far managed to acquire was mainly designed for two projects: Baley’s own apartment-cum-atelier in Paris’s 5th arrondissement, which he decorated in the 1960s, and a series of buildings on a Normandy farm that he renovated for a repeat client in the early ’90s. The pieces for the latter were originally stained black. In the new monograph devoted to Baley, French academic Ambre Tissot highlights affinities between his creations and those of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian period. “The two artists shared a preference for wood planks assembled in a simple, geometric structure that was instantly legible with no superfluous ornamentation,” she writes.

Yet, if anything, Baley’s designs feel more cutting-edge and their forms more dynamic. “They have this radicality but also a very unique French sense of proportion and aesthetic,” says Magen. He feels they can hold their own in any company. “If you put a piece by Baley next to something by Eileen Gray or Mallet-Stevens, it will have the same weight,” he adds. “His work has such refinement.”