April 27, 2015Now approaching 78, architect Renzo Piano continues to take on a constant stream of commissions — but he privileges projects that contribute to “civic life,” from museums to airport terminals and courthouses (Photo by Stefano Goldberg). Top: Piano’s new Whitney Museum engages with its urban surroundings in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District (Photo by Nic Lehoux). All photos courtesy of Renzo Piano Building Workshop

Starchitects may shape the landscape indelibly with their buildings, but they aren’t immortal. Renzo Piano turns 78 this September, and even though he’s at the absolute pinnacle of his profession — having designed hundreds of significant buildings over the decades and winning, among many other accolades, the 1998 Pritzker Prize — he has his eyes set on still more.

“At my age, the pressure is not what you’ve done,” says the affable, bearded and endlessly gregarious Italian architect. “It’s what you have yet to do.” He was recently named “Senator for Life,” a uniquely Italian honorific that dates back to Roman days and seems perfectly suited to him — even if it does remind him of his age. “That’s how you know you’re an old man,” he says, laughing.

All joking aside, however, the breadth of Piano’s current work is stunning. (He confirms what many architects and close watchers of the profession suspect: He turns down many, many offers to design significant cultural buildings, an embarrassment of riches.) The website of his firm, Renzo Piano Building Workshop, lists 18 major projects that are underway, including the first phase of a multi-building northward expansion of Columbia University’s campus, which has been in progress in Harlem for more than a decade and will finally debut in 2016. And Piano’s design for the new Whitney Museum of American Art, which has moved from New York’s Upper East Side back downtown, opens this Friday in the Meatpacking District to much fanfare.

The Genoa-born Piano has become best known for his museum work, having built what is surely a record 24. These include the project that rocketed him to fame as a young man, 1977’s Centre Pompidou in Paris, designed with fellow Italian Gianfranco Franchini and Brit Richard Rogers, as well as the quintessential small museum, Houston’s Menil Collection, and additions to Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Art Institute of Chicago. But he relishes the chance to do any building that “contributes to civic life,” he says, such as his Kansai Airport terminal in Japan’s Osaka prefecture and an upcoming Paris courthouse.

The structure Piano co-designed for Paris’s Centre Pompidou — which famously featured escalators on the building’s exterior— was the subject of huge controversy throughout the 1970s but is now considered one of the 20th century’s most emblematic buildings. Photo by Richard Einzig © Arcaid

RPBW has offices in Genoa, Paris and New York, with Piano splitting his time among the three locations. “First, I have a great office — I have thirteen partners,” Piano says, explaining how he gets it all done. “Some of them have been working with me for forty years. I have something like one-hundred-and-fifty people all together. But I have a rule: I never do more than I can do.”

When we first met last fall, he proudly explained that he had spent the morning not on some managerial task, but thinking about the shape of joints to be used in the new Whitney, which features huge column-free galleries with views of the Hudson, as well as smartly conceived terraces that face the residential side, jutting to within a few feet of the neighborhood-transforming High Line park.

As he greets the international press corps just days before the Whitney’s public May 1 opening, Piano calls the structure a “building that flies above town.” What he means, as will shortly be made clear to visitors, is that transparency and openness create a kind of buoyancy for the museum — which boasts 50,000 square feet of exhibition space inside and 18,000 square feet outside. The galleries have blond wood floors and feel roomy compared to the old Marcel Breuer structure, for all its Brutalist charms. The museum dramatically cantilevers over the entrance lobby, which is glass-walled and welcoming, and you can see right through the space to the river. The structure is grounded by a strong connection to the city, as many galleries are framed by large windows, and specifically to Greenwich Village, where Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney originally founded the institution. (It opened on West 8th Street in 1931.)

The exterior, meanwhile, is asymmetrical and industrial in character, with a blueish cast to its cladding; in some lights it resembles a Precisionist painting by the great American artist Charles Sheeler, who is represented in the Whitney’s collection. As Piano’s buildings are known to do, it appears to reference a variety of civic structures from the outside (New York‘s art critic Jerry Saltz compared its exterior to a hospital — not entirely unkindly, commending its emphasis on function over flourish).

Indeed, the “Building” in RPBW’s name reveals the pride Piano takes in basic engineering. “My father was a builder,” he says. “So I enjoyed that. I was spending a lot of time on sites, just watching.” The bustling port city of Genoa gave Piano an appreciation of the sea, as well, especially the comings and goings of ships — “always moving, nothing stays, everything floats” — which he now connects to his architecture. Not only does a porthole motif appear occasionally in his buildings, but there is a sense of movement in his work.

Rows of well-articulated vertical mullions are one of Piano’s recurring tropes, evoking the colonnades and arcades of classical architecture. “I think it’s because I like vibration, and I love volume,” he says, noting his use of the motif for his freestanding addition to Louis Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. Piano’s simple pavilion with overhanging glass eaves, which has a similar scale to Kahn’s building, opened in late 2013. “This is what gives a sense of the infinite; this is what gives a sense of depth.”

Even when large, Piano’s buildings don’t seem unwieldy; he is a master of approachable scale. The Whitney’s director, Adam Weinberg, says that even though Piano is a thoroughly modern architect, “He’s still something of a classicist and a humanist. He tends toward a simplicity of form. And he can take his liberties on the details.”

“At my age, the pressure is not what you’ve done. It’s what you have yet to do.”

Piano is often cited for his masterful use of natural light: His design for the Menil Collection, in Houston, incorporates an external canopy of louvers that shade the sloping, glass roof, below which a fabric ceiling diffuses the light from outside. Photo by Paul Hester

Piano’s facility for harnessing light is certainly the most commented-on facet of his museum work. “I love playing with light,” he says, “but you have to control it.” He demonstrated his mastery of this game early on, creating an inner layer to the roof structure of the Menil in a curved shape that helps filter the light. Sophisticated louvering is also part of his light-controlling bag of tricks, and one sees echoes of Piano’s influential work on lighting and roofs in projects like David Chipperfield’s Museu Jumex, in Mexico City, and Thomas Phifer’s North Carolina Museum of Art, in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Last year’s most high-profile Piano debut brought together under one new glass roof the galleries of Harvard’s art museums: the Fogg, the Busch-Reisinger and the Arthur M. Sackler. The consolidation includes the old Fogg building plus an addition wrapped in a cladding of glass and cedar, both of which happen to nestle very close to Le Corbusier’s only North American building, the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts. (Referring to the way a ramp from the Carpenter comes within a few feet of the addition, Piano says, “The Corbusier embraces us.”)

All of Piano’s strengths were brought to bear on this project. “The first thing he said was, ‘I can give you more light,’ ” recalls Tom Lentz, the head of the Harvard Art Museums. To that end, Piano focused on the dark, inaccessible and dilapidated Calderwood Courtyard at the center of the Fogg.

The Fogg’s four original floors have arcades looking out into the courtyard — which was, until recently, covered under a light-omitting roof — with galleries beyond. Piano “really reimagined it,” says Lentz. “He extended the courtyard vertically, and the top is now a glass lantern. We can let in whatever amount of light we want, but the light never penetrates past the arcade.”

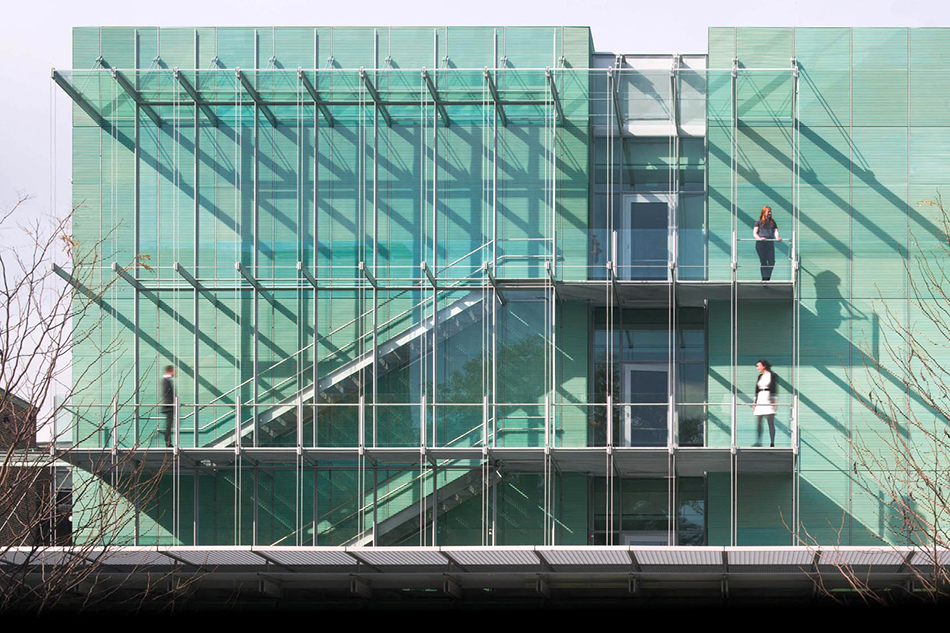

While floor-to-ceiling windows in the new Whitney Museum’s west-facing galleries offer sweeping views of the Hudson River, a number of terraces on its east side allow visitors to feel immersed in the bustling city all around them. Photo by Nic Lehoux

Piano also found a way to emphasize the educational aspect of the three teaching museums (with an astounding combined collection of some 250,000 objects) by including a “lightbox gallery” at the top of the building, providing oblique views into conservation labs. The collections are intermingled in some areas of the museum that are arranged by period, but one floor provides separate galleries for each of the three legacy institutions so that their identities are not lost.

The Harvard project allowed Piano to once again declaim the importance of civic space and openness, something he’s demonstrated with projects like his addition, unveiled in 2006, to the Morgan Library & Museum, whose glass-enclosed courtyard brings together separate buildings of different eras. He calls the revamped courtyard at Harvard a “piazza,” one that can now be accessed by an additional entrance. People can walk through the ground floor of the building without having to pay and enter the galleries.

Approachability, permeability and the importance of exposing the general public to culture have been programmatic themes for Piano ever since he created clear tubes for the escalators of the Pompidou and placed them on the outside of the building. He says that instead of a museum architect, he feels more like an “urban architect,” committed to “letting the city in.” That’s true in Cambridge and in New York, at both the Whitney and his new uptown Columbia campus, which is a 180-degree turn away from the old Ivory Tower idea of the cloistered university.

“Architecture is about making good, solid structures for human beings,” proclaims Piano. That credo has served him well from his days as a young renegade in Paris in the 1970s to the present, where he serves as an éminence grise and the go-to designer for the world’s most prestigious projects. “It’s not just a technical job, but also a spiritual job.”