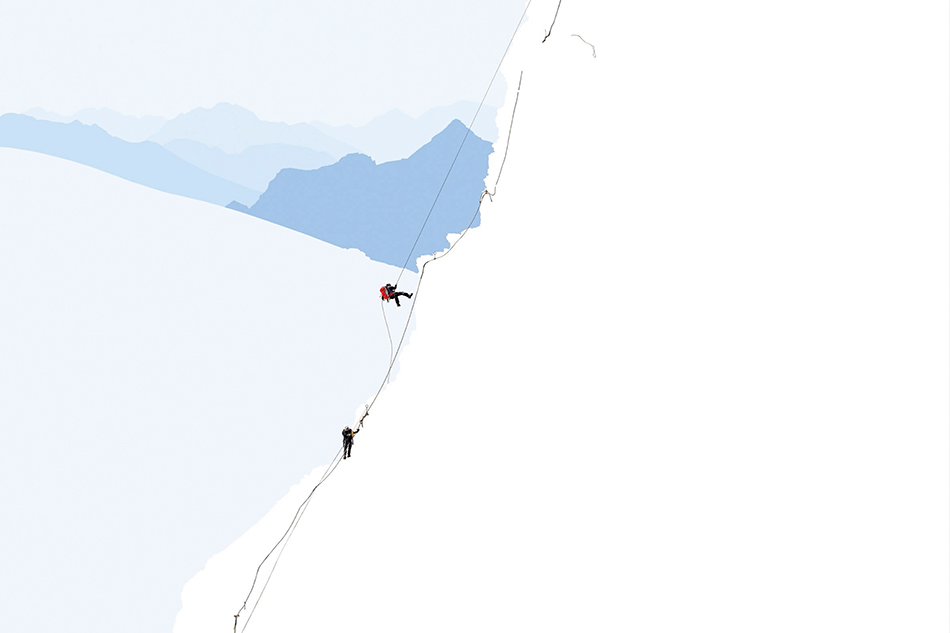

September 25, 2013Alps, Geographies and People 11, 2012, is one of the new works by the photographer Olivo Barbieri currently on view in New York. Top: Alps, Geographies and People 2, 2012

For his latest show of new work at Yancey Richardson Gallery in New York’s Chelsea, the Italian artist Olivo Barbieri, famed for his massive aerial photographs of metropolises from Shanghai to Chicago, stayed relatively close to home, turning his ever-seeking lens on the Alps. While the storied mountains appear as majestic as you might expect, the images are not just pretty landscapes of snowy slopes and rocky outcroppings. Instead, Barbieri trained his camera on the humans intent on climbing these massive peaks. The results are a stunning — if vertigo-inducing — consideration of man’s role in nature.

A continuation of his “PARKS” series, which has featured some of the world’s most spectacular waterfalls as well as the Dolomite mountain range and the blue waters and rocky landscapes of Capri, “Alps — Geographies and People” (on view through November 2) emphasizes the climbers, whom Barbieri described in a recent interview as “reckless and contemptuous of danger.” In a nifty paradox, the tinier the climbers appear in the vastness of the terrain, the more conceptually central they become to the work.

“Alps” makes for an intriguing companion to “Site Specific,” Barbieri’s decade-long study of the modern world’s ever-changing cities. (The title comes, Barbieri says, from his view of the world as a “temporary installation in transition.”) The theme of the built environment is the thread that connects this latest work through to some of his earliest, from the 1970s — nevermind that the Alps were built over a period of hundreds of millions of years whereas Las Vegas took about 70. As Barbieri told curator Christopher Phillips for an essay accompanying the artist’s new book, Site Specific (Aperture): “We’ve created a new kind of urban sublime that combines the elements of awe and fear, just as the 19th-century sublime regarded the great mountains of the Alps.”

“We’ve created a new kind of urban sublime that combines the elements of awe and fear, just as the 19th-century sublime regarded the great mountains of the alps.”

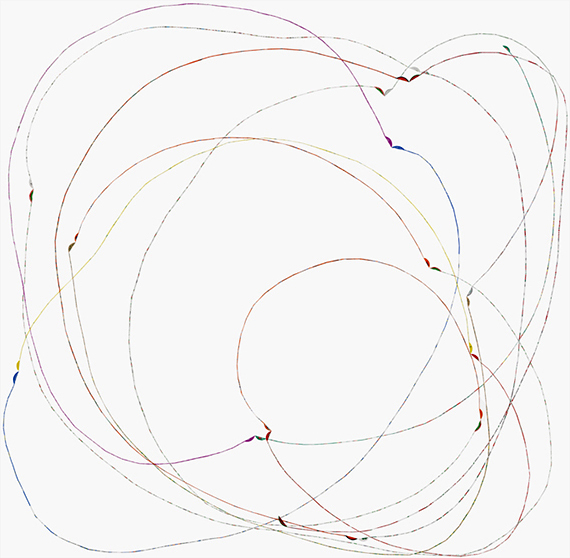

Barbieri, who now lives in Modena, Italy, took his first aerial photo as a child, while flying above his hometown of Carpi, where he was born in 1954. His interest in the artistic possibilities of the technology grew, he says, when he spotted works by Man Ray and Andy Warhol in a museum. He studied photography at the University of Bologna, and, since then, as Phillips notes, the artist’s practice has revolved around his unending urge to innovate. From selective focus, which blurs some elements of a composition while sharpening others, to his breakthrough technique of using a tilt-shift lens from above to alter scale and perspective, making skyscrapers, cars and people appear like child’s toys, Barbieri has pushed the boundaries of photography.

Roughly midway through the “Site Specific” series, around 2007, Barbieri finally abandoned film for digital and embraced the computer’s seemingly boundless opportunities for alteration, leaving the tilt-shift lens behind for his many imitators. In the digital images that followed, his painterly touch comes to the forefront. Skyscrapers in Baldessari-like primary colors look like Minimalist totems, while you could swear reverse black-and-white images were actually drawings. In his hands, a New Orleans junkyard looks like an intricate abstraction, and a close-up of a mother and child captured from a great distance like a watercolor.

Going digital offered Barbieri another practical solution: Constantly changing rolls of film while aloft was a challenge; just holding a camera steady in a hovering helicopter was itself something of a feat. Initially Barbieri says he would take 4,000 to 6,000 frames to get a dozen that were useable. “You must learn,” he says, “like riding a bicycle.”

Whether this ever-inventive photographer is globetrotting, playing with scale, experimenting with technology or pushing the confines of his visual vocabulary, Barbieri’s motivation remains the same: “I like to be lost in geography,” he says, “to try new paths.”