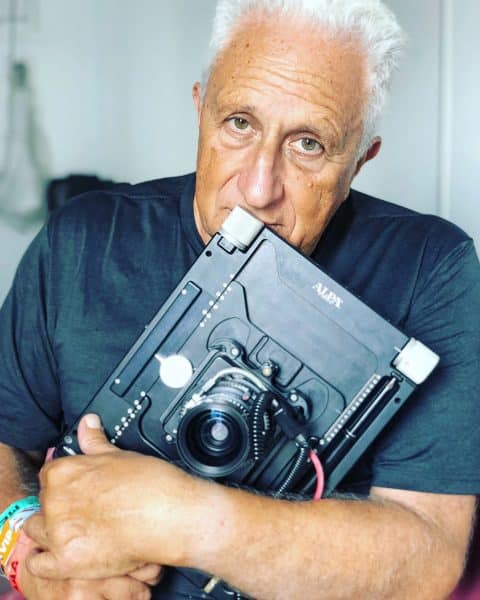

April 12, 2020Massimo Vitali sounds content. “I’m sitting in the garden, in the sun,” he reports by cell phone, “and it’s beautiful. The roses are beginning to bud. The figs and peaches and the lemons are doing really great.” Like most Italians, Vitali hasn’t gone anywhere since early March. But given the necessity of staying inside, he says, “I’m lucky.” A former church, complete with churchyard, in the walled city of Lucca, his house “is a godsend, because there are a lot of places to lie down, a lot of places to work,” explains Vitali, noting that, as a result, even after weeks of confinement, “I haven’t been desperate to leave. I’m very grateful to be home.”

The photographer had his eye on the deconsecrated 14th-century church for quite some time, thinking it would make a wonderfully unconventional home. He knew the 650-year-old building had a complicated history: In the 20th century, it was a gym for fascist youth groups, then a plumbing supply warehouse. Recently, it sat empty for 17 years. Eventually, someone bought it hoping to turn it into a hotel. That’s where Vitali got lucky: The prospective hotelier, he says, had no idea what he was doing, and the project failed. So, the Tuscan church came back on the market at a greatly reduced price. “I’ve been looking at it for twenty years, and all of a sudden it’s affordable,” he marvels.

Vitali, who had been living nearby in a portion of a palazzo that he found too ornate, purchased the church, much of whose old decor had faded. “I like simple things. The church is a good compromise,” he says of the approximately 30-by-60-foot building. Then began a process of turning it and its attached priory into a place where he, his wife, Annette Klein — an art historian and collector of antique jewelry who was instrumental in the church’s redesign and decoration — and their college-age son, Otto, could enjoy comfort without clichés.

Given the long history of the church, the process of updating it was closely regulated. “Everything we did, people from the state superintendents of archaeology and fine art had to watch,” Vitali says. “We couldn’t use machines — it was more like renovating with a scalpel.” In addition, anything discovered on the site was the property of the government. And when Vitali dug down to replace the concrete floor, he began finding shards of 15th-century pottery. The pieces had been used as fill, but that didn’t stop the government from carting away 20 boxes of them.

Luckily, Vitali didn’t intend to do much to the building anyway. “When you buy such an old place, what is really interesting is what has happened during the centuries,” he says, adding, “History makes layers.” And he didn’t want to lose those layers, although he did put on a new roof (the old one had leaked so badly that plants were growing in the building) and install a new concrete floor (with radiant heating). Thanks to quartz powder in the concrete mix, the floor is “shiny but not too shiny,” Vitali reports.

Otherwise, the interior surfaces are as he found them. Even the Mussolini-era fascist motto “Believe Obey Fight” (in Italian) remains on the wall. “I never thought I’d live with a fascist slogan, but it’s part of history,” Vitali says. He also preserved the streaks of white paint people poured over the slogan after the war — another part of history. Wherever the paint was peeling, it’s still peeling. Among the benefits of this laissez-faire approach is that the ceiling vaults remain a sublime blue gray that Vitali says would have been impossible to reproduce.

Working with local architect Paola Sausa, he inserted two new structures — one containing the master bedroom suite, the other Otto’s bedroom and bathroom — while leaving most of the floor space unencumbered. The stairway to Otto’s bedroom also leads to a catwalk (Vitali calls it a passerelle) that provides views of the town through windows high off the ground.

“We couldn’t use machines — it was more like renovating with a scalpel.”

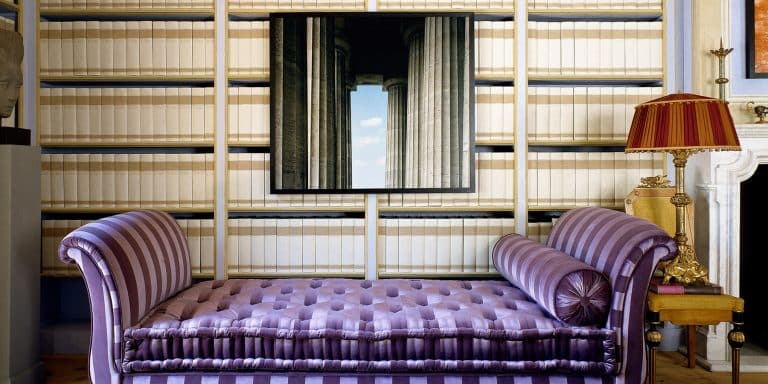

As for furnishing the house, Vitali and Klein are fortunate to be only a short drive from Perignano, home to Edra, the maker of stylish contemporary furniture by designers like Humberto and Fernando Campana and Masanori Umeda. Once a year, the company has a warehouse sale. “So, I started to buy there, and over the years, the owners got to know me, and now we’re friends,” Vitali says.

Sometimes, he trades his services as a photographer for Edra pieces. “It’s one of those very Italian relationships,” he explains, “and I happen to love their furniture.” Examples in the church include a large blue sofa designed by Francesco Binfaré, a smaller orange chaise longue and a greenish chair by the Campana Brothers. Plastic Edra chairs surround a dining table made from an 18th-century wooden top and new iron legs.

There are many less-contemporary pieces, including the 19th-century iron bed in Otto’s room, which was picked up at a local antiques market. In the mix back in the main space are 17th-century dining chairs and a table made by Vitali’s maternal grandfather, who had a small furniture factory in Milan. A 1930s statue by Pietro Melandri is also from that grandfather, who gave it to Vitali’s mother as a wedding present. On one wall near the bottom of the stairs is a framed piece of a ceiling fresco from a Venetian villa; it’s attributed to the school of Tiepolo.

“Every piece here has a meaning,” Vitali says. Even so, he admits the place is a bit messy right now. During the lockdown, with time to kill, he and Annette brought everything up from the cellar for a winnowing. “I just discovered I have twenty-seven pieces of luggage,” he says, sheepishly.

Vitali notes that the courtyard outside the church, with a big linden tree at its heart, is almost as historic as the church itself. “I’ve seen maps from the sixteenth century showing this garden, and the shape was exactly the same,” he says. The doorway to the church is made of local stone from the hills around Lucca. Above it is a cross flanked by two hooded monks, all also carved of the stone. Those monks led people to their executions, Vitali explains, adding that with such a bloody past, “you might think there would be some odd feelings living here, some strange things happening. But there’s nothing like that going on. The place is completely benign.”

Vitali, who was born further north in Italy, in Como, and went to school in Milan, fell in love with Lucca, a small town near Pisa, 25 years ago. Among its distinctions are its spectacular 15th-century walls. “They were built to keep invaders out, but they’ve never been used in battle,” Vitali says. He explains that Lucca was a rich city that bought off its enemies — “and that’s why the walls are in perfect, pristine splendor.”

When Vitali exited those walls before the coronavirus, it was for places like Ibiza and Sardinia, to photograph the sunbathing crowds. But he isn’t a beach photographer. “I am more interested in the people on the beaches than in the beaches themselves,” he says. “I focus on the sociological and the anthropological.” And though he has also shot in parks, plazas and nightclubs, he says that “beaches are a good place to study people. They’re not dressed — they show more, and they show who they are and their attitude toward life.”

His large format photographs are blown up to an epic artwork scale in strictly limited editions (six plus two artist’s proofs) and offered by such galleries as Edition EKTAlux and Dean Project. “Size does matter,” he says, explaining that he wants the images to be big enough for people to see every detail, as if they were in the scenes themselves.

Once the coronavirus is under control, Vitali will again venture out to photograph. “I know that as soon as this stops, I will have a lot of work to do, because I’m really interested in seeing how people will act — maybe they will congregate in different ways. My photography is about studying people, and it will be a great moment to study people in even more depth.”

Of the lockdown, he adds, “It’s something that’s never happened and, hopefully will never happen again. It’s important to record what happens next.”