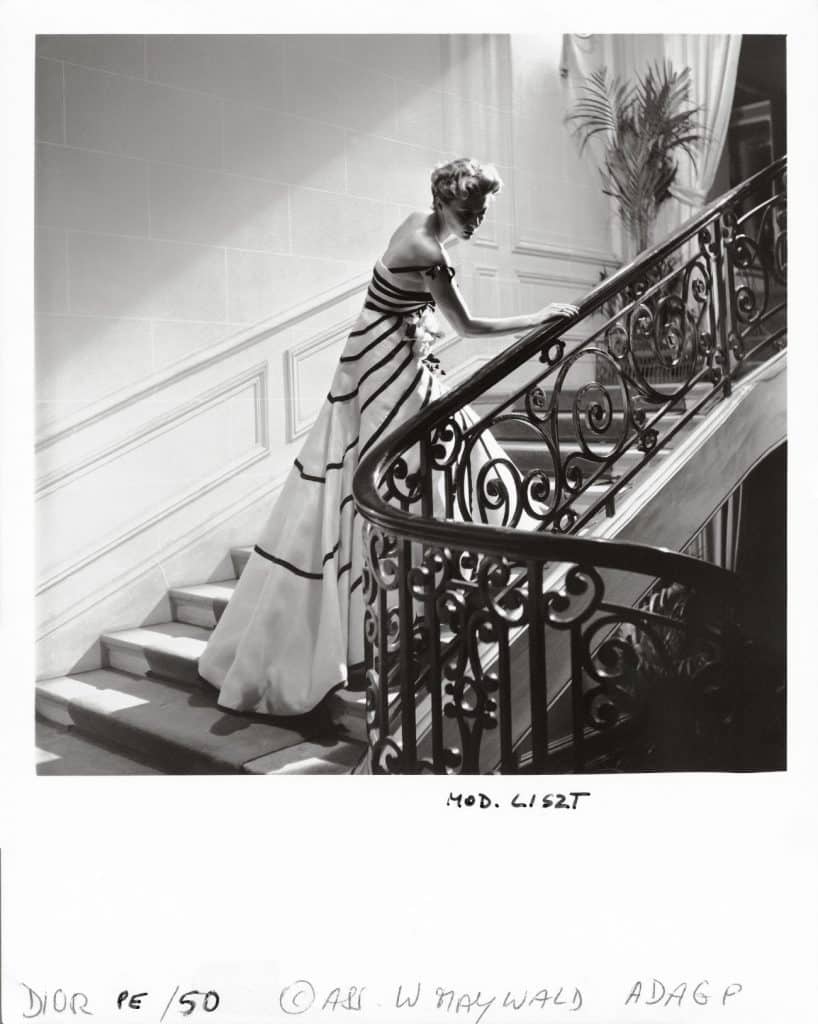

November 11, 2018Victor Grandpierre and Georges Geffroy were close collaborators of Christian Dior and designed his townhouse together, according to Maureen Foot, author of Dior and His Decorators (Vendome). Above, the blue salon of Château de la Motte-Tilly, a Louis XV country house updated by Grandpierre. Top: A model wears Dior. Photo courtesy of ©Association Willy Maywald

Christian Dior’s new house in Paris reflects in turn the times of Madame Bovary, Whistler, Louis XVI, and the Augustan Empire — and always the taste of Dior, who edited each detail,” declared the October 1953 issue of Vogue, referring to the sumptuously appointed, flower-filled 16th arrondissement townhouse. The magazine also credited Parisian interior designers Victor Grandpierre and Georges Geffroy, who worked with the fashion maestro to achieve the home’s exuberant balance of classicism and modernism. A stunning new book by Maureen Footer — fittingly titled Dior and His Decorators (Vendome) — chronicles the close collaboration among the three, revealing analogues of the New Look in lush yet eclectic designs for living.

Dior and Geffroy first came together in the 1920s, when they ran in the same bohemian circles as creative talents like artist Christian Bérard and poet Max Jacob. (Later, Geffroy helped engineer Dior’s entry into the world of couture by introducing him to designer Robert Piguet.) When Dior established his own couture house, in 1946, he tapped Grandpierre and later Geffroy to interpret his personal vision within interior spaces. “Grandpierre and Geffroy [were] as steeped in fashion as their friend and client,” writes Hamish Bowles, editor at large for Vogue, in the book’s introduction. “Grandpierre had been a fashion photographer, and Geffroy a designer for Jean Patou, a forward-thinking rival to Gabrielle Chanel in the 1920s.”

Grandpierre and Geffroy both collaborated with Dior but always separately. “They were so different — Geffroy a larger-than-life showman, Grandpierre refined and reflective — that they were little more than acquaintances,” says Footer. “However, they ended up designing Dior’s townhouse together, as there is a tradition in France of hiring two decorators, one for private spaces, the other for the reception rooms.” In addition to collaborating on the townhouse, Grandpierre worked extensively with Maison Dior, masterminding the aesthetic of the couture house, from interiors to packaging.

Wearing a gown from Dior’s Autumn/Winter 1953 couture collection, model Sophie Malgat stands in the Grandpierre-designed winter garden of Dior’s home. The photo, Sophie Malgat in Gray Chiffon Dior in Dior’s Paris Home, 1953, is by Mark Shaw.

In the Mark Shaw photograph on the front of the book’s dust jacket, offered by Liz O’Brien, model Sophie Malgat stands in the Grandpierre-designed winter garden of Dior’s home, framed by a wall covered in Chinese embroidered silk and the cresting wave of a curved, button-tufted sofa in tobacco-colored leather. The ruches and flounces of her pale gray ball gown (from Dior’s Autumn/Winter 1953 couture collection) echo those of the room’s Austrian shades and shantung portières.

“That dress is not a classic reinterpretation of a Franz Xaver Winterhalter portrait dress or a Worth dress. It’s very much a Dior dress,” says Footer, explaining her choice of cover image. “And the interior design is not just a re-creation of a great nineteenth-century house or eighteenth-century house — it’s very much that of one individual. Grandpierre and Geffroy had the ability to blend and break from what had previously been very rigid rules in French interior design and create something very independent, just as Dior was doing in his clothes.”

Footer sat down recently with Introspective to discuss the intimate connection between couture and interiors, the enduring influence of her three subjects and some of her favorites among the discoveries she made in the course of her research.

“For his friend Claire-Clémence de Maillé, Grandpierre designed a bedroom around a flowering Indienne document fabric and a château-appropriate mix of painted and marquetry furniture,” Footer writes.

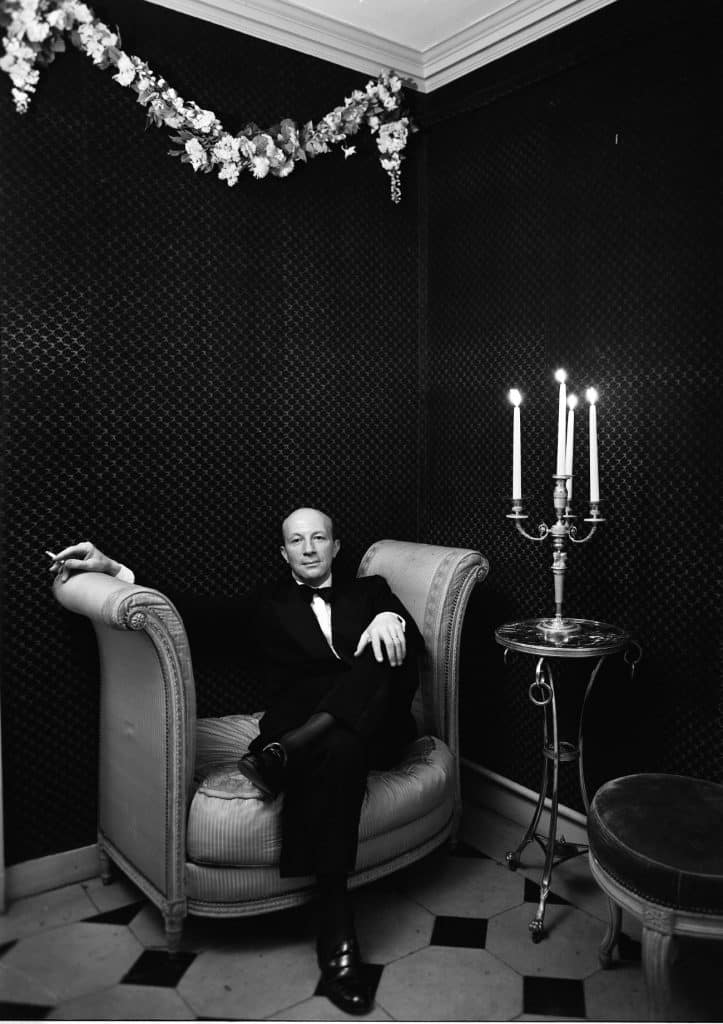

“Paul Strecker, one of the artists in the stable of Dior’s art gallery, painted a young Dior, whose dreamy vision encompassed the past but remained in the moment,” Footer writes.

When did you come upon the work of Grandpierre and Geffroy for Dior?

After college, I worked at Vogue, and I was frequently in the archives. That’s where I saw the photos of Dior’s personal house by Grandpierre and Geffroy. I remember thinking, “Oh, what glamorous-sounding names!” The rooms were so sensuous, and they also emanated the sense of an individual’s personal haven. They had layers of contemporary and eighteenth-century elements and ones referencing the Belle Époque, as well as Chinese textiles and contemporary art. The use of color and the richness of the fabrics all really struck me. After that, I virtually never heard about Geffroy and Grandpierre, but the names stuck with me. I was always curious to know more, and when I finished my book on [American interior designer] George Stacey, I thought, “Let’s look at the same era, mid-century, but let’s go to France this time.”

What led Dior to work with Geffroy and Grandpierre on interiors?

I think one thing that really connected them was that they shared a nostalgia for the France that, between World War I and the nineteen twenties, had disappeared. As much as they were modernists and constantly incorporating the new, that was a shared touchstone, emotionally and aesthetically. What drew Dior to Grandpierre and Geffroy was not simply taste. They were friends, and they all had this vision of French savoir vivre — the very traditional French lifestyle that was vanishing and yet had represented French culture since the eighteenth century.

“Referencing the 18th century, the façade of Dior’s beloved childhood house, and the Belle Époque aesthetic of [French artist Paul César] Helleu, gray spelled elegance to Dior,” Footer writes. “It appeared in the collections, the packaging, and the couture house, and became synonymous with the Dior brand.” Photo by © Mark Shaw/MPTV Images

Absolutely. For Grandpierre, probably the most articulate example is what he did for Maison Dior, for the couture house. He intuitively understood how to create a background to show clothes, and he intuitively understood Dior’s inspiration. If you look at a Dior dress, it’s basically a Belle Époque profile: the little shoulders, the little waist, the full skirt. But, of course, Dior, being a modernist at heart, shortened it. He made it shockingly strapless, shockingly low-cut. Grandpierre was doing that in parallel. He took a traditional townhouse — the beautiful nineteenth-century townhouse where Dior’s headquarters still are — and he stripped it down, took out all the frippery, the fussy plasterwork, and made it very architectural, very spare. He understood Art Moderne and industrial art from the twenties, and then the thirties became slightly more baroque but still streamlined. And he understood that the modern moment is always an accumulation of the past, but it’s also looking forward. So, he had this very pared-down modernist interior and then selectively added back elements that spoke the Dior language: the Louis XVI chairs, the Austrian shades. There was very little decoration and a very controlled palette. What Grandpierre was doing was creating a parallel vocabulary for Dior’s vision. Dior exercised it in clothes. Grandpierre put it into what we now call Louis-Dior style.

How did Dior and Grandpierre decide upon the couture house’s signature gray-and-white palette?

Dior had always loved gray. He felt it was the color of understated elegance. Grandpierre reached for it because it was a subdued reinterpretation of Versailles. It became a perfect neutral but also an elegant foil for Dior’s dresses. These were often in wonderful jewel and spring-like colors, and having a very neutral, calm interior behind them was great.

Grandpierre designed a Roger Vivier–Christian Dior shoe boutique in 1955, displaying the products like artwork. “Naturally, gray and white and Louis XVI seating defined the space,” Footer writes. “In a time before computers matched paint colors, the formula for Dior gray was a strictly guarded secret.” Photo by © Sabine Weiss

Was Geffroy’s approach to working with Dior similar to that of Grandpierre?

For Geffroy, it was a more literal translation. Geffroy had worked in couture. He loved couture fabrics like silk velvets, was fascinated by couture techniques, and brought both passions to his interior design. He upholstered walls, which is very sensual and very Geffroy, but he didn’t always simply upholster as we know it today. He borrowed techniques of draping and folding and flouncing that you use in a skirt. He had an extremely talented, adaptable workroom that was really willing to experiment with him. So, you see that happening — you see it in the passementerie he uses and in details on pillows and lampshades. He was always borrowing inspiration from sources that nobody else tapped, because there was no other interior designer who knew couture and sewing techniques the way he did. He was doing a very literal interpretation of postwar Dior couture in interiors: the colors, the sensuality.

Grandpierre was especially instrumental in defining the Dior codes, what we know today as the Dior brand. What happened after Dior’s death?

Dior died suddenly in 1957, at the age of fifty-two, and Grandpierre worked at Dior through the late seventies. He continually reinterpreted the Dior brand. He added cane and wicker, which are now very much a part of the design, because they’re fresh, they’re modern, they reference gardens, and Dior loved flowers. Then, as Dior moved into more-contemporary times, Grandpierre created a men’s boutique with stainless steel and mahogany, still using gray and white. When Dior decided to get into ready-to-wear, Grandpierre created the Miss Dior boutique, which had track lights and clothing hanging on stainless-steel rods — always enough references to make it an identifiably Dior environment.

Your research included delving into the Dior archives. Do you have any favorite finds?

The whole research process was fascinating. The Dior archives are so deep. I found letters from the business office of Parfums Christian Dior discussing with Grandpierre his designs and how expensive they were and trying to rein him in. But Grandpierre’s thought, particularly after Dior died, was “I have to protect the Dior vision!” It was so interesting to see the back and forth through the correspondence.

“Borrowing liberally from Brunelleschi, Geffroy employed Renaissance perspective to achieve quiet drama in the hallway of Robert Ricci’s home,” Footer writes. “Nailheads translated velvet into boiserie.” Photo by © Condé Nast Paris

One of your interview subjects was Pierre Bergé. How did that go?

I was apprehensive about meeting him, because I had always heard how difficult he could be. But he had been really fond of Grandpierre. Grandpierre had designed his first apartment with Yves Saint Laurent. I just feel so fortunate that I got to him [before he died, in September 2017] and learned his stories. He was one of the few people I spoke with who had known Grandpierre who could really talk about his temperament, his personality, his intellectual ability. I also interviewed Pierre Cardin [who worked at Dior from 1946 to 1950]. He had these wonderful stories about Dior’s famous Bar jacket. Dior made the waist so small that when even his war-emaciated models breathed, the buttons popped off, and Cardin was constantly sewing them back on, just before the first collection.

In researching the book, what did you find most surprising?

My huge surprise, and it struck me over and over again, was that I felt like I was looking at our own time. But this was 1947. It was such a disruptive time and such an unsettled time. So many people were so upset. There were political changes. Economically, France was decimated by the war, and it took a long time for industry to come back. Technology was changing things. The turmoil felt familiar. What I loved was the intelligent response of these three men. They were all modernists and really had their hand on the pulse of their time and were very much a part of contemporary culture, but they also realized what can be gained by looking at history. It tells you how you got where you are. It gives you a broader perspective on a narrow moment. It’s also an incredible source of richness that can be applied to contemporary life. And in addition to the fun of re-creating the era and the beauty of the pictures, I hope that message will come through, because I think it will uplift all of us.

Purchase This Book

Or Support Your Local Bookstore