February 10, 2019Christian Dior’s 1947 Bar Suit announced a new era in women’s fashion with its accentuated curves and lavishly full skirt, a stark contrast to the utilitarian looks of the war years (photo © Laziz Hamani, courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London). Top: The Ateliers section of the exhibition displays the intricate toiles, or mock-ups, of the house’s workshops (photo © Adrien Dirand).

Walking into the Victoria and Albert Museum on a cold, gray London morning, fed up to my cashmere beanie with the political uncertainties on both sides of the Atlantic, I was ready to be transported to a better world by “Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams,” the V&A’s latest revelatory fashion exhibition (on view through July 14). In February 1947, just two years after the end of World War II, a similarly expectant audience had packed Monsieur Dior’s new Paris atelier, eager to view the French couturier’s debut Spring/Summer haute couture collection. The fashion crowd and the moribund haute couture industry were yearning, comme tout Paris, for security and prosperity, desperate to discard the drab, sexless, utilitarian garb imposed by wartime deprivation. They needed to dream anew.

And Dior delivered: He designed a collection for a bright, optimistic future. “It’s quite a revolution, dear Christian!” exclaimed Carmel Snow, the prescient American editor in chief of Harper’s Bazaar, famously proclaiming, “Your dresses have such a new look.” The press ran with the description, christening Dior’s collection the New Look. “God help those who bought before they saw Dior,” said Snow. “This changes everything.”

“This” was a new feminine silhouette of extravagant elegance, and its embodiment stands front and center at the exhibition’s entrance. Called the Bar Suit, it comprises an ivory silk-shantung jacket with soft shoulders, nipped waist and padded hips over a voluminous black wool skirt. Every girl and boy should own it. It is that rarity: a composition as wearable today as it was some 70 years ago, despite its contradiction of contemporary cultural mores. No upcycled, gender-fluid eclecticism here. The collection definitively declared that opulence, luxury and femininity were in. Dior’s skirts could have 40-meter-circumference hems, and outfits could weigh up to 60 pounds. They were cut and shaped like architecture, on strong foundations that molded women and “freed them from nature,” Dior said. Rather than rationing, his ladies wanted reams of fabric and 19-inch waists enforced by wire corsets, and the fashion world concurred. The debut got a standing ovation.

Dior’s well-known fascination with flowers is explored in the Garden section. Photo © Adrien Dirand

Dior works with the model Sylvie, circa 1948. Photo courtesy of Christian Dior

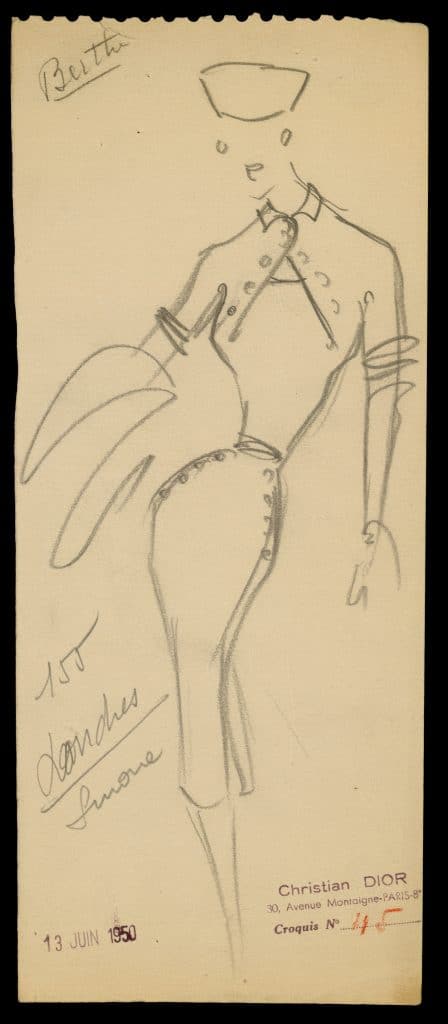

Christian Dior was born in Granville, on the Normandy coast, in 1905. His prosperous haute bourgeois parents wanted him to become a diplomat despite his interest in art and architecture. However, they agreed to bankroll an art gallery, which Dior opened in 1928 in Paris with a friend. This was the start of his rise in the city’s creative milieu, where he befriended Pablo Picasso and Jean Cocteau. After seven years as an art dealer, Dior retrained as a fashion illustrator, eventually landing a job as a fashion designer for Robert Piguet, and in 1941, following a year of military service, he joined the house of Lucien Lelong. Just five years later, with the backing of industrialist Marcel Boussac, the ascendant Dior established his own fashion house, at 30 avenue Montaigne in Paris.

One could turn around and leave “Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams” after seeing the important Bar Suit if the V&A’s only intention was to reveal the man and his enduring impact on fashion. But walk on in. The show, based on an earlier exhibition at Paris’s Musée des Arts Décoratifs, is kaleidoscopic, spanning 70 years of the House of Dior and showcasing the skills and craftsmanship of its ateliers. Oriole Cullen, V&A curator of modern textiles and fashion, has divided the exhibition into 11 themed sections, such as Historicism (exploring the influence of historic dress and the decorative arts in the label’s designs) and the Garden (a source of inspiration for both its fashions and its perfumes).

Amid sets designed by French scenographer Nathalie Crinière, Cullen has brought together more than 500 objects in total, including 200 haute couture garments displayed alongside accessories, jewelry, perfume bottles, magazine covers, photographs and ephemera. Adorning the mannequins are hats by milliner Stephen Jones, some made expressly for the exhibition but most designed for the collections (his mask for Spring/Summer 2018 is, well, a modern miracle). Shoes from Dior’s celebrated collaboration with footwear designer Roger Vivier, drawings by René Gruau, Aurora Borealis crystals created for Dior in 1956 by Swarovski and more are shown in the Diorama section, aptly named since it also includes to-scale miniature dresses.

After 10 years at the head of the house, Dior died suddenly of a heart attack at the age of 51. Thousands of people from all walks of life flooded the streets of Paris to honor the man who had revived the city’s pride in the aftermath of the war, reestablishing it as the capital of international fashion.

European and Russian royals were among the inspirations for John Galliano’s Autumn/Winter 2004 haute couture Christian Dior collection. Photo © Laziz Hamani

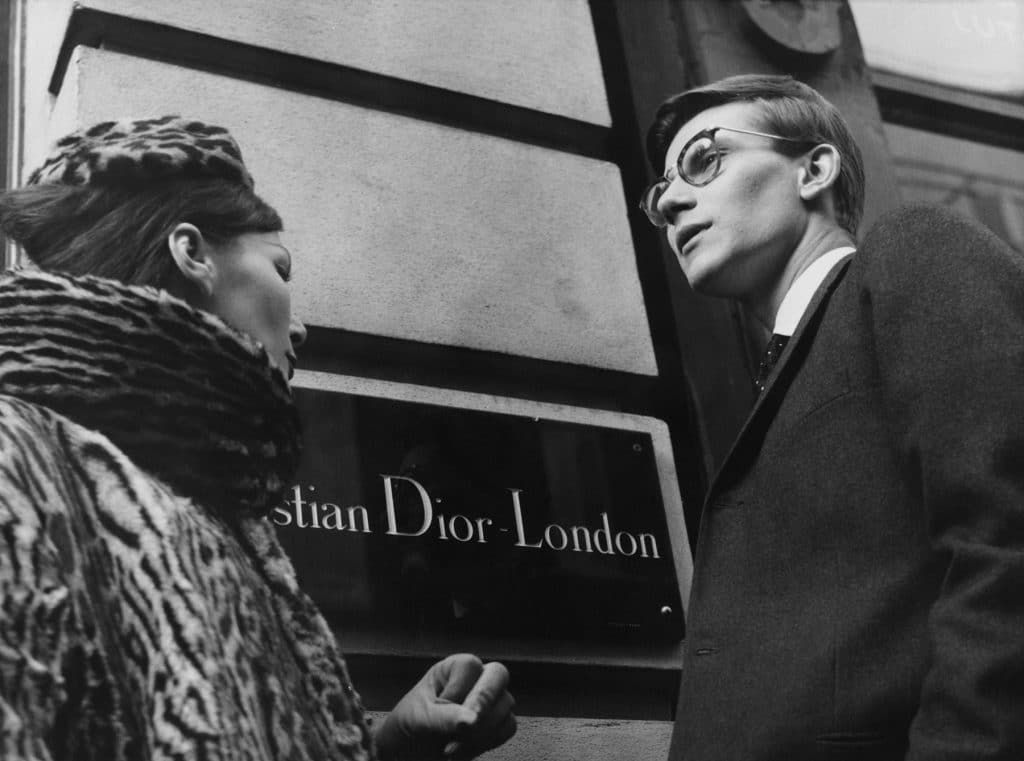

It is fascinating to walk through the installations and compare and contrast the Monsieur’s work with that of the six artistic directors who succeeded him. Each found inspiration in the archives and the art of haute couture to reimagine the house’s aesthetic legacy in his or her own clearly defined way: Yves Saint Laurent brilliantly and fleetingly; Marc Bohan reliably and loyally; Gianfranco Ferré with structured excess; John Galliano with volatile genius; Raf Simons with achingly beautiful rigor; and Maria Grazia Chiuri, the first woman and current director, with a keen feminist vision.

Perhaps most importantly, though, Cullen has introduced an additional focus — Dior’s love for the United Kingdom, exhibited in the section titled Dior in Britain. For this display, Cullen has delved into the museum’s extensive fashion holdings, as well as those of the Fashion Museum Bath, and in addition to the Bar Suit, she has included a second pièce de résistance: Princess Margaret’s 21st-birthday gown, on loan from the Museum of London. Unlike her sister, Queen Elizabeth, who wears only British designs, Margaret was free to wear what and whom she liked and struck up a firm friendship with Dior during the many occasions he came to the UK to present his collections at various stately homes, including Blenheim Palace.

Princess Margaret poses for a 21st-birthday portrait in 1951 in a Christian Dior gown. Photo © Cecil Beaton, courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The script on Maria Grazia Chiuri’s Christian Dior haute couture Spring/Summer 2018 dress was inspired by a 1950s Dior folding fan. Photo © Laziz Hamani, courtesy of the Dior Heritage Collection, Paris

The last section of the exhibition, the Ballroom, is truly breathtaking. Thankfully, banquettes (covered in suedette in Dior’s favorite shade of gray) are provided so that rapt visitors may sit to enjoy the light show that takes the octagonal space from magical day to starry night. It’s an ideal backdrop for the glittering eveningwear on view. Celebrity red-carpet gowns are here, including the diaphanous pleated-tulle creation worn by Natalie Portman at the 2018 Hollywood premiere of Vox Lux, Rihanna’s off-white silk-taffeta strapless gown and trailing coat from the 2017 Cannes Film Festival and, naturally, the scandalous floor-length navy silk slip Princess Diana wore to the 1996 Met Gala in New York.

Heading toward the exit and marveling at the bravado of such a finale to a fashion exhibition not shy of sensory detail, unexpectedly, around the corner, I encountered a single calm postscript, albeit placed in front of infinity mirrors. It is a delicious nude pleated-silk-tulle gown from the Spring/Summer 2018 haute couture collection, its lavish skirt boldly embroidered with “Christian Dior” in stylized script, inspired by a fan he gave out in the 1950s. OK, so it has a tiny waist, but women these days are more likely to achieve this on a healthy diet of kale and chia seeds than with corsets. Today, fashion’s silhouettes are a free-for-all, and femininity means having the confidence to choose one’s style. It is simply dreamy. And when I left the museum, the sun was out! All will be well.