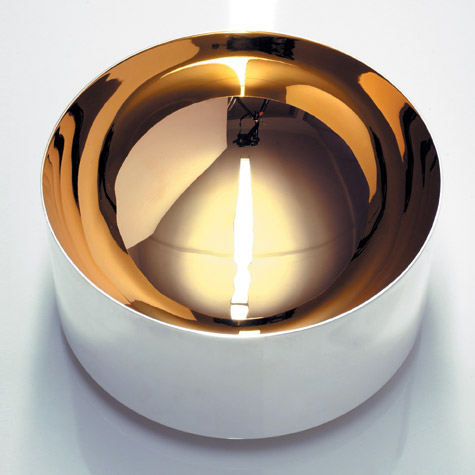

June 15, 2015Martin Szekely’s current exhibition of Artefact tables at the New York gallery Salon 94 marks his first solo show in this country in 20 years. Top: The textured, slate-gray table tops are based on a pebble that the French designer digitized, enlarged and then carved into single blocks of mica-flecked Brazilian quartzite.

New work by French furniture designer Martin Szekely is now on view at the gallery Salon 94 on New York’s Upper East Side (through June 26), and it’s an unusual show on several counts. Szekely’s first solo exhibition in the United States in more than 20 years, the exhibition displays a series of tables, called Artefacts, which are unlike anything Szekely’s done before. In place of the spare, linear forms for which he is known, the 59-year-old designer presents coffee and side tables with gray quartzite tops that, through the use of computer-guided cutting and grinding machinery, reproduced identically — if at much larger scale — the contours of a pebble Szekely found on a beach in Normandy. The show is also an atypical presentation for Salon 94, a venue best known for exhibiting provocative artists such as Marilyn Minter, Laurie Simmons and Francesca DiMattio. “I don’t show a lot of design. When I do it is the work of a kindred spirit,” says the gallery’s proprietor, Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn. “Martin is more of a conceptual artist than a designer. His work is understated and has autonomy. It’s what you want to put in a room alongside strong and aggressive art.”

Szekely is one of the most admired yet enigmatic figures in contemporary design. Certainly, no other designer today so successfully straddles the worlds of commerce and high culture. Day to day, Szekely works as a product designer for leading European luxury and lifestyle brands: He has created glassware for Perrier and Heineken, jewelry for Hermès, cutlery and tableware for the silver-maker Christofle, perfume bottles for Roger & Gallet and a wine bucket for Dom Perignon, among other projects.

At the same time, he is among the foremost makers in the rarefied field of limited-edition furniture that blurs the line between art and design. Szekely’s furnishings and their precise, geometric forms draw frequent comparisons with the furniture of Donald Judd. Such pieces were the central feature of a 2011 mid-career survey of Szekely’s work at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, and are prized by a distinguished group of collectors that includes couturiers Karl Lagerfeld and Azzedine Alaïa and the luxury goods conglomerateur François Pinault. The interior designer Muriel Brandolini says that she has “acquired more than one hundred of his pieces for myself and for clients.” Craig Robins, the real-estate developer and founder of the Design Miami fair, has several Szekely pieces, among them a table he uses in his breakfast room. “Martin Szekely is one of the key designers of this generation,” Robins says. “He has this feel for material and shape — and the result is simple, beautiful and brilliantly executed. He’s not about flash. Szekely does in design what minimalists did in art.”

Szekely is the son of two artists. His father, Pierre, was a well-known creator of organic, abstract sculptures, several of them monumental public commissions; mother Vera was a noted ceramist. It’s a surprising fact, given what is most compelling about Szekely’s work: He vehemently resists self-expression. Working toward an end that perhaps only another French intellectual could understand, Szekely seeks to reproduce only pure, universal, objective forms in his furniture. He refuses to work like almost all other designers. His credo is “ne plus dessiner” (a phrase used for the title of the Pompidou show) meaning “draw no more.” For Szekely, “drawing” — sketching, awaiting a flash of inspiration — is shorthand for self-reflective, emotional and personally expressive design. “The way I work is more like that of a scientist,” he explained while in New York to oversee the installation of his work. “I observe. I analyze phenomena. I experiment.”

“Szekely has this feel for material and shape — and the result is simple, beautiful and brilliantly executed. He’s not about flash. He does in design what minimalists did in art.” —Craig Robins

Testing, research and trial-and-error have produced some remarkable designs. Szekely’s endeavors using new materials have resulted in the SL table (2003), a rectangular table composed of a sandwich of Corian and honeycomb aluminum; Solar Noir (2007), a mirror made of black silicon carbide, the material NASA uses for its space telescopes; Heroic Carbon (2010), a series of furniture pieces made of an aluminum-and-carbon fiber composite; and, in 2008, a large oval table with an impossibly thin top made of concrete. Szekely’s technical and technological investigations have also led him to l’Armoire (1999), a cupboard composed of a single sheet of aluminum, folded like origami, and Bing One (2005), a cylindrical, solid crystal side table made by pouring liquid glass into a mold and letting it cool for three months. Sometimes the designer seems to take a “let’s see what happens” approach. The ovoid tops of his 2007 Tore tables are based on the forms of random droplets of mercury. He created his Des Plats group of serving platters (2000) by spraying molten glass inside a free-form mold made from flexible ribbons of metal.

Resting on slender gold-plated legs, the Artefact tables place natural, organic form and the awe-inspiring potential of contemporary technology in dialogue.

Perhaps representing an evolution in his process, Szekely’s new Artefact tables are the result of a kind of philosophical, as opposed to purely scientific, inquiry. “I have wondered if humans can reproduce nature,” he says. “These tables are how I ask that question.” And if at first glance these pieces seem out of place in Szekely’s body of work, with a little context you can understand how they fit in: Along with their simple geometric structures and shapes based on accidental phenomena, they reflect Szekely’s ongoing search for a kind of objective formal purity. After all, the beach pebble on which they were modeled was the product of eons of slow, relentless, natural forces; it was created by the laws of physics — a perfect, authorless design. As Szekely says: “I see no great necessity to think so much about the self. I would rather think about the world.”

His work, in turn, gives viewers a great deal to ponder.