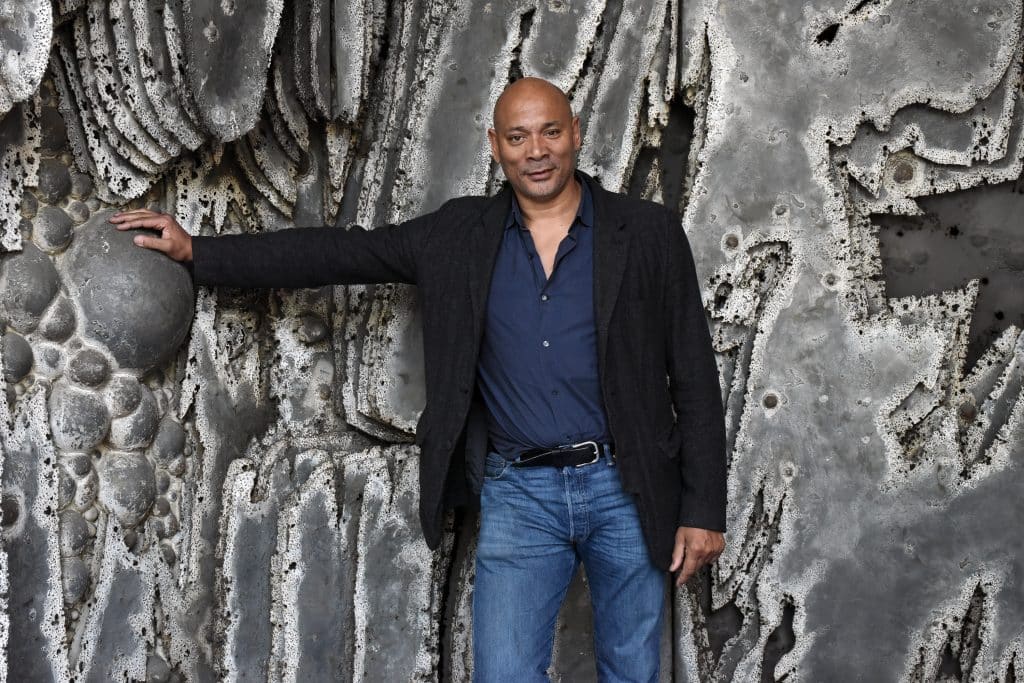

January 10, 2021Hugues Magen may be the only gallery owner ever described by the New York Times as “eye-riveting,” “all man” and “a knockout” “in flaming-red pajamas.” That was in 1994, when he played the role of Stanley Kowalski in the ballet version of A Streetcar Named Desire. Magen had come to New York from his native Paris to dance — first with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, then with Dance Theatre of Harlem, where he was a principal dancer for more than a decade. “It was quite a roll,” he says.

But as he approached his 40th birthday, just before the turn of the millennium, he knew it was time to do something else. “I needed to trade one passion for another,” says Magen. He discovered his second career in 1999, when he saw a pair of LCW chairs by Charles and Ray Eames on the sidewalk outside a Soho furniture store.

Magen, who knew some furniture dealers in Paris, bought the chairs for a few hundred dollars, carefully disassembled them, then carried them to Paris in his luggage. A dealer friend put them on display and in less than half an hour sold them to an important collector for many times what Magen had paid in New York. The former dancer was hooked.

He started making regular trips to Paris, bringing American furniture with him and carrying French furniture of the early postwar period back to New York. For five years he sold items out of his apartment. Then, in 2004, he and his then wife, April Magen, opened Magen H Gallery. (April Magen is now the director of global partnerships for DesignMiami.)

More than just a salesroom, the gallery became his classroom, the place he taught the world about unknown or little-known designers. In 2009, the gallery moved to an Alan Wanzenberg–designed space on East 11th Street in Manhattan. Magen, now 61, lives in Tribeca and commutes to the gallery by Citi Bike. He talked with Introspective about his design discoveries and how he’s weathering the pandemic.

What were the first things you bought in France to sell in New York?

In the early days, it was Prouvé and Perriand, which I was crazy about. I also bought a lot of smaller objects, like lamps. Back in New York, I would put them in my backpack and ride my bike around the city, showing them to dealers like Alan Moss, Larry Weinberg, Patrick Marchand, Bernd Goeckler and Maison Gerard.

How did you learn about the pieces you were selling?

Most of it was asking questions and observing. And I did a lot of reading. I had very little formal schooling. I’m what you would call an autodidact.

You quickly graduated from showing well-known figures like Perriand to introducing lesser-known designers to the market.

That’s always been my goal. I want to start new conversations, not talk about things people already know.

Is Pierre Chapo an example of that?

Yes. I had my first Pierre Chapo show in 2017. But I spent five years before that doing the research and looking for the most interesting examples. I developed relationships with people who owned his pieces, including some who had ordered them from Chapo and his wife directly.

I didn’t buy every piece that came along. I was looking for the kind of work that would promote my idea of what Chapo was — a master wood craftsman who drew inspiration from Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, Charlotte Perriand and others.

Who are the other designers you’ve helped bring to the public’s attention.

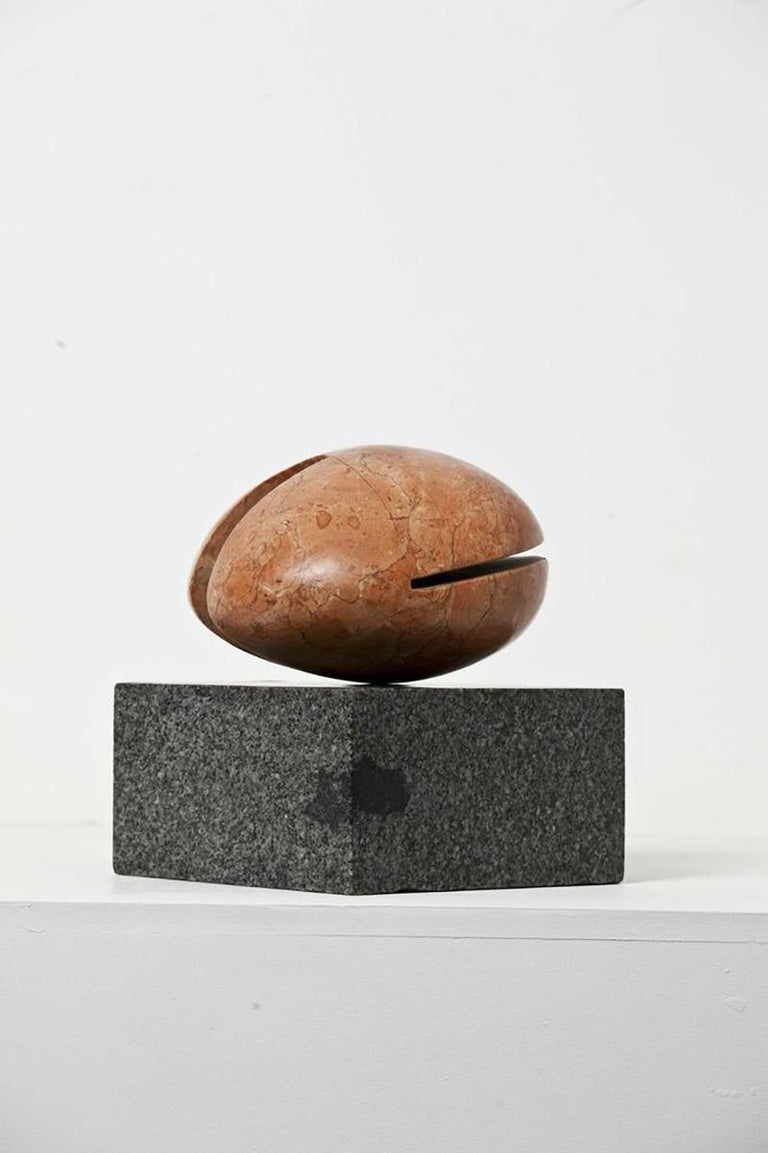

Seven years ago, I did the first show of La Borne ceramics, at a time when even people in France were not aware of the work. And I started showing Pierre Székely in 2005 at DesignMiami. Now everybody wants him. I was the first one to show the sculptor François Stahly in New York, and I showed the artist Alain Douillard, known for totemlike scrap-metal sculptures, as well. I also mounted the first U.S. retrospective of Pierre Sabatier, the absolute master of the sculptural mural walls so popular in France in the sixties and seventies.

That’s quite a list! So, is there anyone left to discover?

Yes. I have two extremely important exhibitions that will be taking place over the next few years. One that I can talk about is Hervé Baley [whose angular wooden furniture also recalls work by Wright]. Over the years, I’ve collected perhaps one hundred pieces of his that have never been shown anywhere. Not even in France.

How did you do that?

It took a lot of time and energy. Baley didn’t make a lot of pieces, but I developed relationships with owners, with the estate. It’s an important body of work, and I’m very happy to be bringing this project to completion. [The pandemic has delayed the show by a full year.]

How did you learn about Baley in the first place?

As an architect, he did many houses with Dominique Zimbacca, whose work I have also shown. They were influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright and tried to follow his principles of organic architecture. That created a schism, because back then, the ideas of Le Corbusier were sacrosanct. But Zimbacca and Baley wanted to change the dialogue about modernism in Europe.

You mentioned two shows.

There is someone else I am working on. It’s someone you’ve never heard of, but you’ve seen the work. But it is in its infancy. I have to put my hands on a lot more pieces before I can reveal the name.

How has the gallery adjusted to the pandemic?

Everything has changed. Containers don’t arrive, so we cannot show new merchandise. It’s an entire cycle that has been slowed down. And people weren’t walking in off the street. But now, we’re seeing a little more life in the gallery.

For November and December, we organized an exhibition called “The Decorator’s Eye,” where we divided the gallery into three sections, each curated by a different interior designer: Robert Stilin, Michael Bargo and Alyssa Kapito.

And we’ve had a much greater presence on the Internet. 1stDibs has provided a platform. It’s our saving grace. On our own website, we’ve been promoting stories people can relate to. We have a Staying Home With video series, where people show how they’re living during the lockdown. In one episode, I’m in my own apartment in Paris, where I spent the first six months of the pandemic. In another episode, our gallery director, Nathalie Dheedene, takes people into her home on Long Island.

Do you sell all your best pieces?

There is a group of pieces that I have had for eighteen years in my New York apartment that I would never want to sell. Perriand, Le Corbusier, Prouvé — I was infatuated with their work at the beginning, and I still enjoy their presence. The core group also includes a lamp by Valentine Schlegel and a ceramic sculpture by Pierre and Vera Székely. I hope I will never have to sell any of them, but you know how life is.

Is there a piece you’re sorry you sold?

I wish I still had the incredible sandblasted wood screen by Pierre Székely that I showed at my first DesignMiami in 2005. It was bought by Donna Karan for about $375,000, which was crazy money back then. Still, I wish I had not sold it. I can’t tell you how many people have come to me hoping this piece is still available.

You told me that your mother was from Guyana and your father from Guadeloupe. How does it feel being a rare Black person in the world of high design?

When I started, there were no Black dealers, and there are very few today. The last time I was at DesignMiami, I looked around, and I was the only one. I’m very lucky that I had the chance to get where I am. I try not to limit myself to what the outside world imagines me to be.