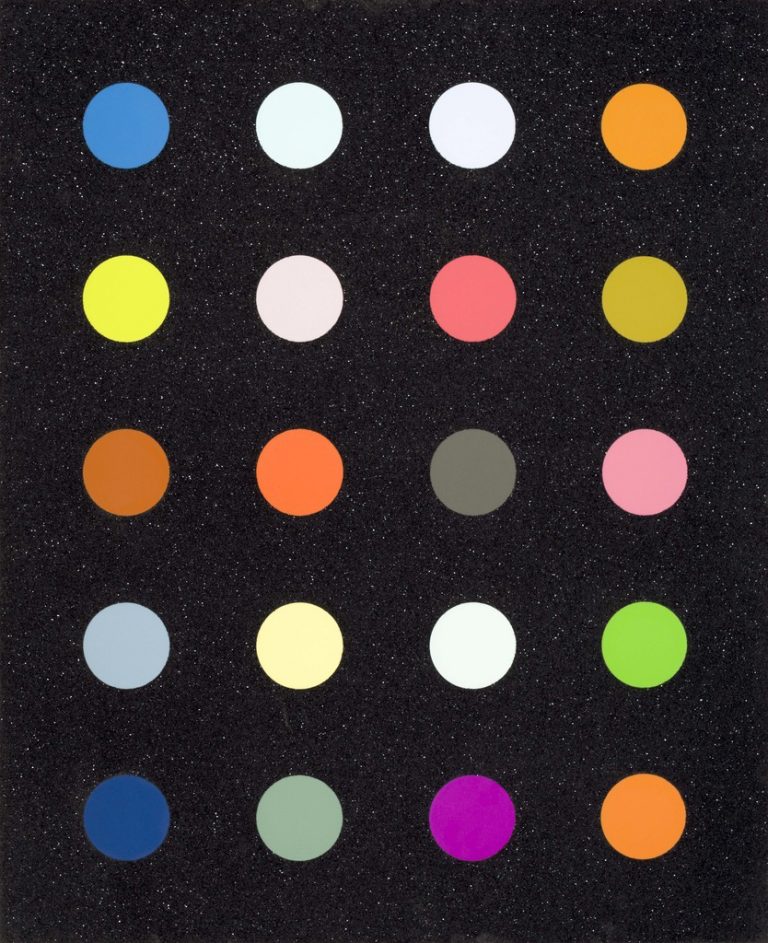

June 26, 2013“I love to shock,” says New York architect and designer William Georgis. Top: In an Upper East Side townhouse’s library, Georgis combined skunk-patterned pillows on the custom sofa, a Sciolari chandelier, Carlo Bugatti chairs and a Damien Hirst medicine cabinet. All photos by T. Whitney Cox, courtesy of Monacelli

Architect and designer William Georgis has that Bruce Willis grin. You know the one: amused, mischievous and more than a little wicked. When coupled with his laddish looks — if one ignores the slightest wisp of gray peaking out from the square-cut black mane above his forehead — a natural question arises: Was young Billy a naughty boy?

The 55-year-old Georgis can’t recall playing any elaborate childhood pranks on his sister, Demetra, or his brother, Theodore Jr., back in their hometown of Oak Park, Illinois, and he doesn’t admit to ever being caught with his hand in a cookie jar. “I went to school all my life and worked all my life,” he insists, “just like my mother told me to do.” However, he adds, “I wouldn’t say I was a dull child. The perversity and transgression have always been there.”

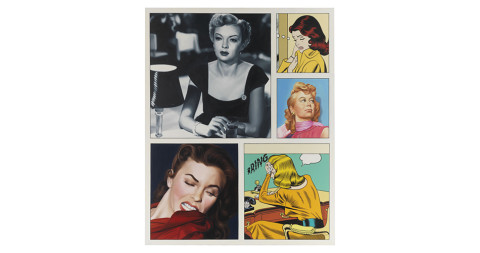

Ah. Right. That might explain the Fifth Avenue powder room Georgis designed for two empty-nesters, lining it with bullet-strafed mirrored panels. It could also offer some insight into the 2003 American Hospital of Paris show-house bedroom he created for an imaginary deranged woman (black moiré walls, red satin sheets, rubber coverlet), or the “panic room” he outfitted six years later for the Kips Bay show house (Uzis, grenades, an oxygen tank and plenty of vodka). It might also illuminate the particular recess of his mind from which he excavated the inspiration for what appears to be a bloodstained carpet in the lobby of a hedge fund’s offices (along with a console once again shot up with lethal ammo).

“I love to shock,” he concedes in Make It Fabulous: The Architecture and Designs of William T. Georgis, his newly published monograph from the Monacelli Press. Yet careers built singularly on shock value have a short shelf life. What elevates his interiors above tongue-in-cheek one-liners are the multiple layers of art and design knowledge, historical context and narrative thrust that underpin them. The bullet-riddled mirror panels, for example, are the work of an incorrigible storyteller. “I can imagine an aging Joan Crawford walking in, looking in the mirror and pulling a mother-of-pearl-handled pistol out of her clutch to obliterate the lies,” Georgis writes in the book.

Behold, for example, the pairing of a 19th-century French crucifix and a Roman bust of Heracles, which can be found in the dining room of the Upper East Side townhouse that he shares with his companion, art curator and advisor Richard D. Marshall. This is not mere caprice. “You have to be able to coax a meaning from the dialogue that goes beyond visual splendor,” he tells me. “There has to be an intelligent component. Here you have the pagan and the Christian. You have different ideas of masculinity, the homoerotic element of two naked men, the Twelve Labours of Heracles and the Stations of the Cross — you could just keep riffing on it.”

Not, mind you, that Georgis is one to cast aspersions at the sheer joy of visual splendor. Among his early influences were the lavish Thorne Miniature Rooms at the Chicago Art Institute. They put the history of decorative arts in context for him and fueled what later blossomed in his interiors as a theatricality of rich, sumptuously worked materials, striking juxtapositions and impressive scale. As a teen, he also led guided tours through Oak Park’s many Frank Lloyd Wright residences, which fueled his predilection for modern architecture. And his familiarity with the Chicago residences designed by David Adler was essential to his understanding of the way historic European principles could be adapted to more modern domestic American architecture.

“You have to be able to coax a meaning from the dialogue that goes beyond visual splendor. There has to be

an intelligent component.”

The derelict townhouse Georgis redesigned for himself and his partner features zebra-patterned silk-velvet slipper chairs of his own creation and a Julian Schnabel painting.

Encouraged to pursue these passions by his real-estate developer father, Theodore Sr., and his homemaker mother, Mitzie, Georgis’s education began with the Bauhaus-centered art and design curriculum of the Illinois Institute of Technology, then continued at Stanford (where he earned a degree in art history) and, finally, Princeton (a masters in architecture). After a short stint with Robert Venturi and almost 10 years at Robert A.M. Stern’s office, a South American couple asked Georgis to design their apartment at Manhattan’s Carlyle Hotel. His partner, Marshall — whom he’d met in 1989, when Marshall was a curator at the Whitney Museum — had introduced him to this art-collecting couple, and their confidence in him spurred Georgis to set up his own firm in 1992. (Another project for this couple appears in Make It Fabulous.)

Since then, Georgis has built a stalwart clientele of adventurous art collectors who, though they might live on Park Avenue, don’t tend to request the old-money aesthetic that once dominated the thoroughfare. “It’s a new generation of families who aren’t interested in plugging into the formula,” says Georgis. “When I went to Princeton, that WASP class was the ascendant voice. Now there are newcomers from other social and cultural groups who are interested in the idea of difference. That entrenched demographic isn’t interested in what I do; they wouldn’t come to me.”

In the Southampton Colonial Revival home, French glass lanterns from the 1940s hang above a burl wood coffee table and slipper chairs. A Sam Samore photo looks out over a mod billiard table.

Georgis explains that his clients are “new merchant princes,” including developer Aby Rosen and collector and dealer Alberto Mugrabi (son of the Israeli-born collector José Mugrabi, who owns, among many other works, the largest collection of Warhols in the world). They don’t balk when he suggests hanging half a dozen 1940s Japanese-style glass lanterns over a chunky burl wood coffee table on a flokati rug in the living room of a traditional Hamptons mansion. They thrill to his amalgamation of a 1970s Sciolari stainless-steel chandelier with a custom Chesterfield sectional sofa, chain mail curtains, Carlo Bugatti chairs and an alligator skeleton hovering in midair in a library. “Remember what they’re hanging on their walls: insane crucifixions by George Condo!” Georgis points out. “The imagery itself is provocative.”

Timid his clients are not. They come to Georgis precisely because he empathizes with their quirks and kinks, even ones they might be uncomfortably revealing. For instance, Georgis noticed one client liked to look at his wife in a, well, less-than-innocent way. So he designed a bath with louvers so he could watch her shower. “At first, they were a little embarrassed that I’d seen that,” says Georgis, who admits to his own fascination with voyeurism. (This is a man, after all, who also designed a guestroom enclosed in a transparent glass bubble.) But in the end, the couple felt more understood than, shall we say, exposed.

As he has matured, Georgis has in some respects become less confrontational. He admits, for instance, to not always feeling the need to work against historic architecture in a space, which for years was his default response to traditional surroundings. But does that mean his interiors are any tamer? “I don’t know,” he demurs, his lips curling into that Willis grin. “What do you think?” The answer: Not so much.