December 5, 2016Gardening enthusiast Bunny Mellon was also a formidable collector. Eighty items from her Virginia library are on display at the New York Botanical Garden, including this oil painting, Dandelion, 1990, by Sophie Grandval. Top: Detail of Magnolia grandiflora, ca. 1737, by Georg Dionysius Ehret. Images courtesy of Oak Spring Garden Library, unless otherwise noted

Rachel “Bunny” Mellon, who died in 2014 at the age of 103, was a philanthropist, collector and self-taught horticulturist. Both before and after her marriage to banking heir Paul Mellon, she designed public as well as private gardens, her most famous commission being the redesign of the White House Rose Garden at the behest of Jackie Kennedy.

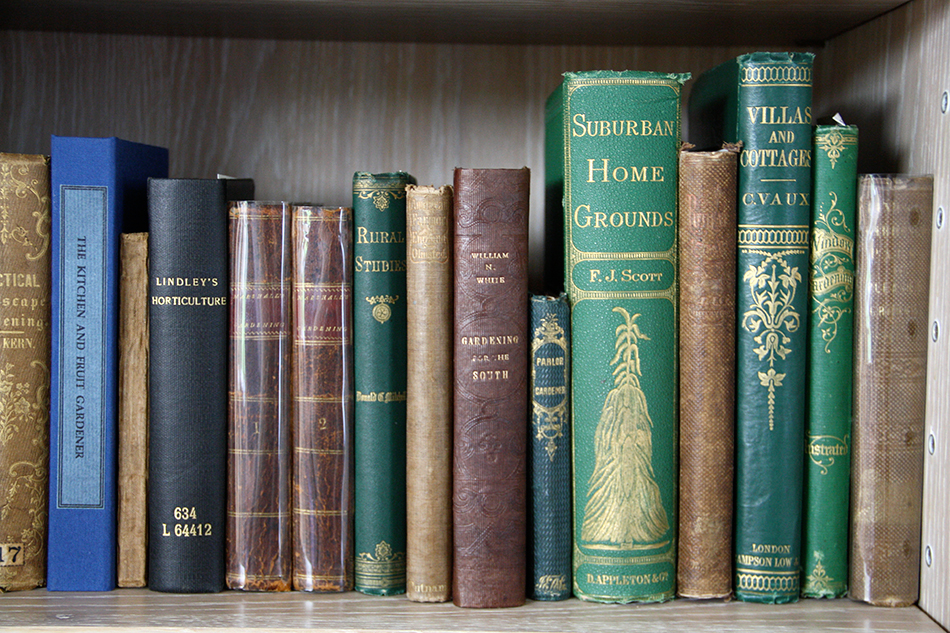

Mellon spent many decades working on her own gardens at Oak Spring Farm, in Upperville, Virginia, and her love of gardening extended to purchasing books, manuscripts and botanical art, first instigated by her need for reference materials. This, in turn, led her to start collecting seriously when still in her 20s. In later years, she frequently remarked that “a library is built during a lifetime; it doesn’t happen overnight.”

This was certainly true in her case. By the time she died, her collection had grown to more than 16,000 objects — books both modern and rare, manuscripts, works of art and artifacts encompassing horticulture, landscape design, botany, travel and literature. For many years, her holdings were scattered among several locations. In 1976, however, she began working with the architect Edward Larrabee Barnes on plans for a library building on her farm. The Oak Spring Garden Library, completed in 1981, became the repository for her still-growing trove. The collection has always been available to visiting scholars, but upon her death, Mellon established a foundation with the goal of making the collection more accessible to the general public.

Pot of Flowers II, 1958, is a crayon drawing by Pablo Picasso.

As a first step in this direction, nearly 80 of the rarest and most interesting of her works are now on display through February 12, 2017, in the Mertz Library of the New York Botanical Garden (NYBG). The curators of “Redouté to Warhol: Bunny Mellon’s Botanical Art” — Susan Fraser, director of the NYBG’s Library; Lucia Tongiorgi Tomasi, a leading expert on herbals and botanical art and the author of two publications documenting Mellon’s collection; and Tony Willis, Mellon’s longtime librarian — have assembled a feast of riches. They have focused on the rare and unique, being careful not to select works held by other botanical libraries. And, of course, they wanted to give viewers an idea of the depth and breadth of Mellon’s holdings.

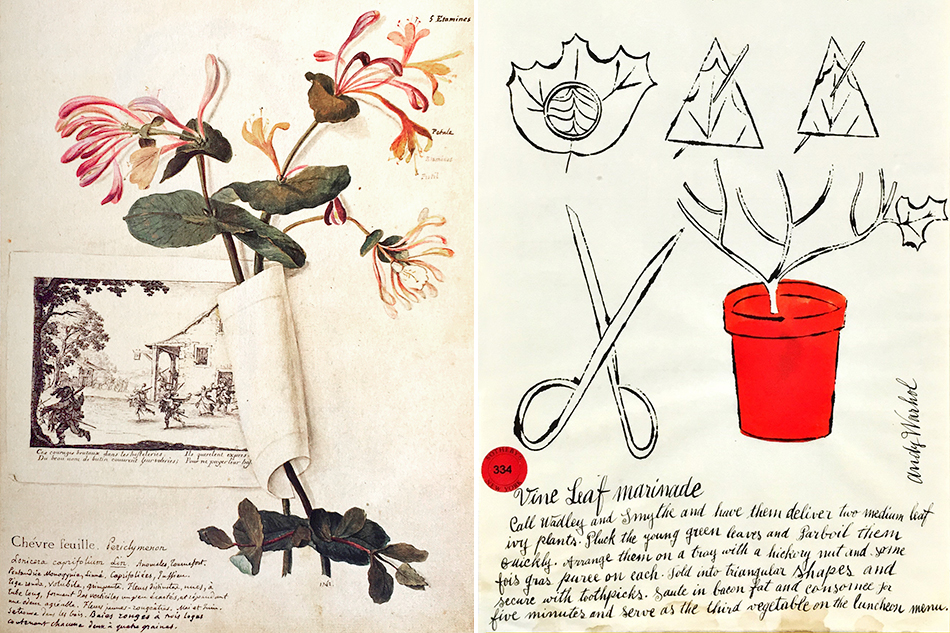

The exhibition scales the past and the future, from a 14th-century manuscript containing hand-colored depictions of plants and animals to two 20th-century Pablo Picasso crayon renderings of pots of flowers and a Henri Rousseau oil of what appears to be a boat filled with an assortment of blooms. There is even a delightfully whimsical recipe for Vine Leaf Marmalade in ink and watercolor by Andy Warhol. In between, the show zigzags from meticulous bookkeeping records of tulip sales during Holland’s 17th-century bout of tulip mania, to a large group of copper Jan van Kessell paintings from the same period that depict butterflies, spiders, lizards and insects and were originally displayed in a Dutch cabinet of curiosities. There are also three gorgeous late-18th- and early-19th-century Pierre-Joseph Redouté watercolors on vellum and much, much more.

“A library is built during a lifetime,” Bunny Mellon was known to observe, “it doesn’t happen overnight.”

A 1982 photo captures Mellon looking through a horticultural book while her terrier, Patrick, keeps an eye on the goings on outside. Photo by Fred Conrad for The New York Times

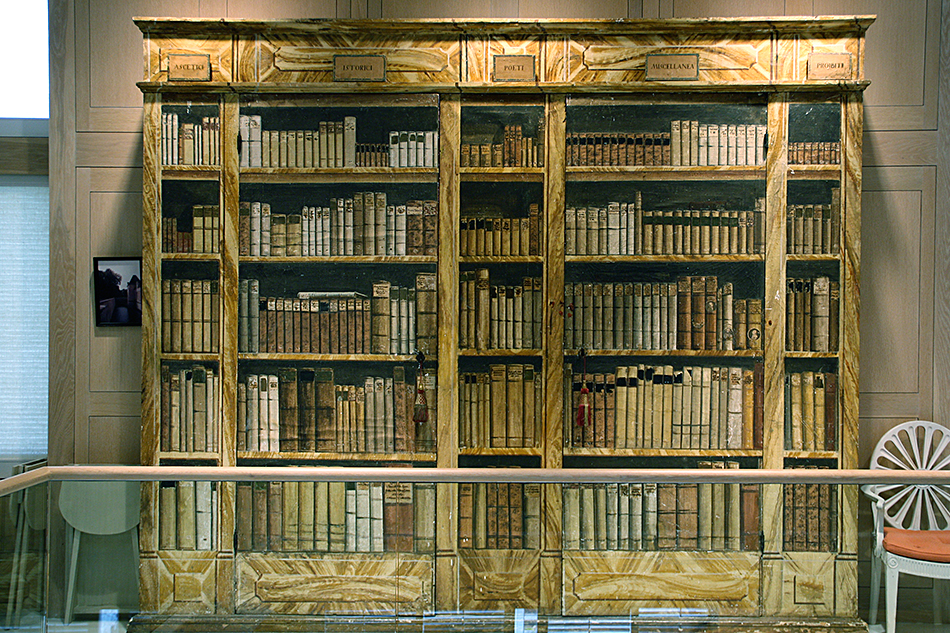

Hung in the Library’s rotunda as a prelude to the show are four slightly larger-than-life-size photographs of the floor-to-ceiling trompe l’oeil panels that Mellon commissioned from the French artist Fernand Renard for the walls of her greenhouse. They attest to her love of this art form. (An accompanying photograph of the panels in situ evidences the impeccable order and elegance of her greenhouse — even the potting table is immaculate.) We sense immediately that we are in the presence of a person of taste and discrimination.

It’s hard to choose favorites, but a 1990 oil painting of a dandelion by Sophie Grandval that literally jumps off the wall is hard to pass up. I was also intrigued by two extremely accomplished watercolors of a turnip and a wood strawberry, both painted circa 1735–36 by Elizabeth Blackwell, a well-known Scottish illustrator in her day. They are an important reminder that creating botanical art was, even then, an acceptable occupation for women. (According to Fraser, Blackwell was a gifted amateur who started selling her work to raise money to get her husband released from debtor’s prison.) Among the portraits in the show, Augustus John’s moody 1911 oil Dorelia in the Garden, is a standout, and who could resist the two exquisitely fanciful dandelions (circa 1910) with gold stems and nephrite leaves emerging from a crystal vase in the style of Fabergé?