May 22, 2022When I moved from New York to Los Angeles in 1989 to work for House & Garden magazine, one of the first stories I wrote was about the tea parties given by the photographer and Hollywood insider Jean Howard in her Beverly Hills living room, which was designed in the 1940s by silent film star turned decorator to the stars William Haines, better known as Billy.

Haines’s mid-century projects — for clients including Betsy Bloomingdale, in Los Angeles, and Walter and Leonore Annenberg, at their Sunnylands estate in Rancho Mirage — displayed a modern, casual elegance. Both the furniture and the rooms he designed epitomized the laid-back Southern California lifestyle.

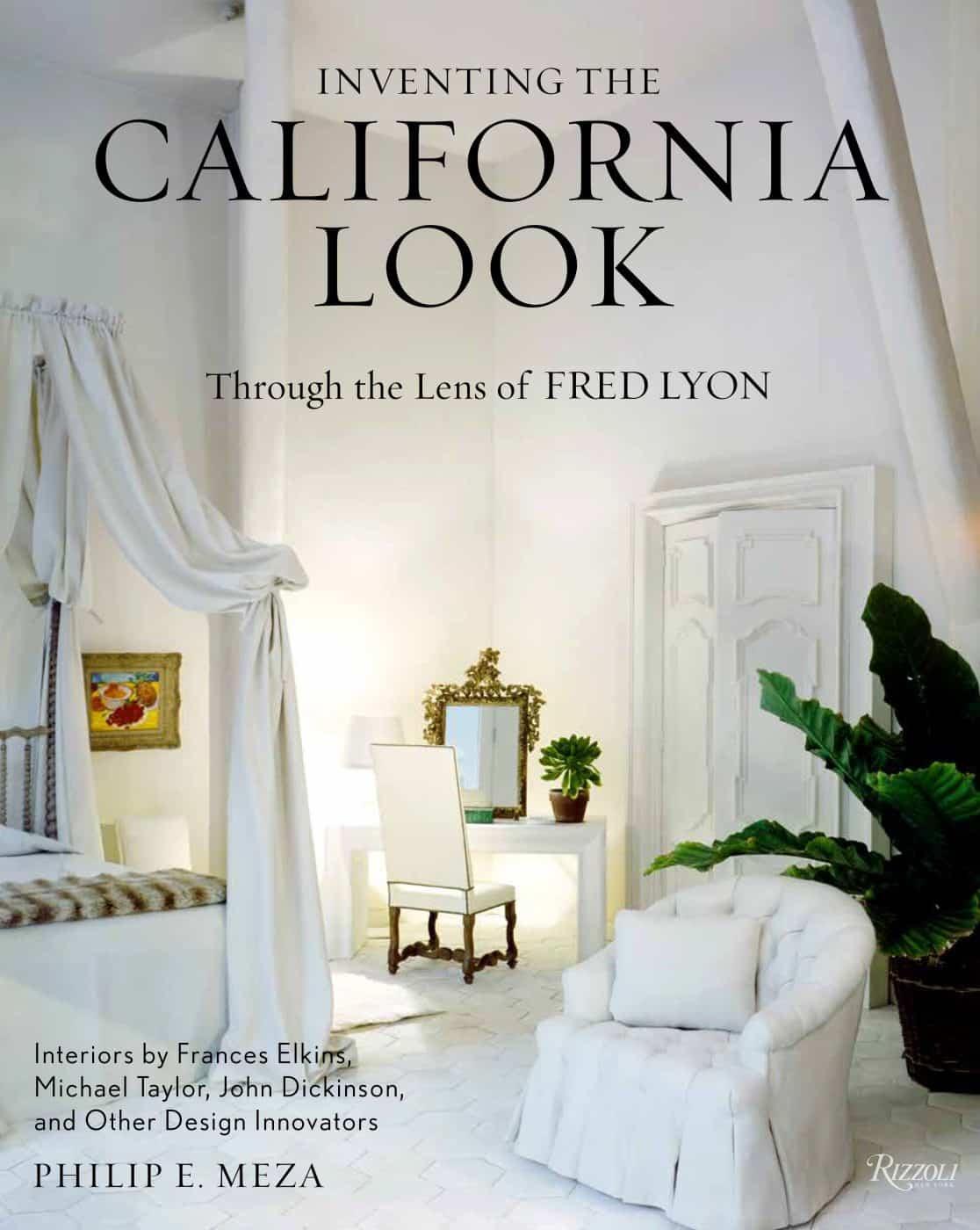

The new Rizzoli volume Inventing the California Look: Interiors by Frances Elkins, Michael Taylor, John Dickinson, and Other Design Innovators provides a unique window into the mid-to-late-20th-century talents whose work defined a cutting-edge West Coast aesthetic. Among the Dickinson projects included is his own home, an 1893 converted firehouse in San Francisco’s Pacific Heights neighborhood. Its living area, seen above, featured Victorian chairs and an Art Nouveau table topped by lamps of his own design. Top: Taylor deployed an all-white scheme in a Bay Area home he designed in 1960. All photos by Fred Lyon

At the time, the magazine was also publishing projects by contemporary L.A. designers like Waldo Fernandez and Kalef Alaton, who carried this low-key but glamorous approach into the present.

During those early days at House & Garden,, I was introduced to design in the Bay Area, too. I visited houses by the San Francisco modernist architect Gardner Dailey, who was a favorite of the city’s elite from the 1930s through the ’60s, and I met Dorothea Walker, a local contributor to the magazine for more than four decades. She knew everyone who was anyone in local society.

Walker championed decorators, like Michael Taylor, who she thought were doing something new to define design on the West Coast, and she collaborated frequently with photographer Fred Lyon, whose elegant but inviting work did as much as the designers themselves to popularize what came to be known as the “California Look.”

As I learned more about 20th-century design in and around San Francisco, a clear picture of the look emerged — relaxed yet refined, defined by the use of clean-lines, light and bright palettes and a mix of old and new. It was an aesthetic that celebrated the locals’ unhurried way of life.

The patrons embracing this look were a rather clubby group of wealthy, sophisticated and adventurous people who were not afraid to enlist the services of architects like Dailey or forward-thinking interior designers like Taylor. Nor were they averse, on occasion, to filling a modernist house with antique furniture — because their designers did so in an unstuffy, modern and entirely West Coast way.

The aesthetic that this symbiosis between clients and creators helped define is celebrated in the new Rizzoli book Inventing the California Look: Interiors by Frances Elkins, Michael Taylor, John Dickinson, and Other Design Innovators. Written by Philip E. Meza, with a foreword by scholar and curator Jared Goss, it features images and commentary by Lyon — now in his 98th year — who shot all the photographs in it for magazines like House & Garden and Vogue from the 1940s through the ’80s.

As the book captivatingly chronicles, this is the period during which the look developed, with San Francisco serving as a hotbed of cutting-edge design and architecture.

In his foreword, Goss notes that the groundwork for locals’ fascination with avant-garde decor was likely laid in 1927. That’s when of-the-moment designer Jean-Michel Frank imagined the interiors of a penthouse apartment on Russian Hill for Templeton Crocker. The railroad and banking heir had iconoclastic tastes, which Frank indulged with parchment-covered walls and boxy white-covered armchairs.

By the 1930s, Frances Elkins, a friend of Frank’s, was using his elegantly spare furniture for a house in the city’s Pacific Heights neighborhood that she was decorating for James D. Zellerbach, who later served as ambassador to Italy, and his wife, Hana.

Elkins used a rectangular sandblasted-oak Frank cocktail table in the bar, which was adjacent to the card room; the pale color scheme of both, combined with the Ekins’s Spider chairs and plaster wall lights by Alberto Giacometti, produced an effect that was decidedly understated and modern — key qualities of the California look.

For the second house he lived in on Telegraph Hill, finished in 1974, San Francisco socialite Whitney Warren Jr. worked with decorators William “Billy” Baldwin and Tony Hail to re-create, according to Lyon, the decor Elkins had developed for his first house there. Lyon goes so far as to suggest that Warren had architect Gardner Dailey design the new house to exactly reproduce the rooms and spaces in order to accommodate the furnishings that he liked in the first house.

Lyon met Elkins on his very first interiors shoot, in 1947 for House & Garden, at a glamorous, light-suffused house on Telegraph Hill. Elkins had decorated it using antique and then-contemporary furniture that contrasted with Dailey’s modernist architecture. (The client was socialite Whitney Warren Jr., whose father was one of the architects of New York’s Grand Central Terminal.) The designer liked Lyon’s photographs, and they worked together many times up until her death, in 1953.

In 1951, Elkins designed the interiors of another Dailey house, for the wildly successful Ford dealer Albert “Speed” Schlesinger and his wife, Irma. Lyon’s black-and-white photographs convey her elegantly spare approach, mixing — according to Stephen M. Salny, in his book Frances Elkins: Interior Design — austerely elegant furniture by Robert Adam with swagged velvet curtains and antique rugs.

Relatively early in his career, Taylor designed this San Francisco bedroom overlooking the Golden Gate Bridge for the daughter of the successful Ford dealer Albert “Speed” Schlesinger and his wife, Irma. The rest of the apartment had been designed by Elkins, who had recently died and whose aesthetic had been a major influence on Taylor. The room’s green-and-white decor defers to the views of the Golden Gate Bridge and the Palace of Fine Arts. (The Schlesingers’ daughter went on to be the style-setting socialite Nan Kempner.)

Meza writes that the late 1950s represented a “passing of the torch from Elkins to the next generation of designers.” Among the most successful of this new guard were Michael Taylor, John Dickinson and Anthony Hail.

An Elkins devotee, Taylor quickly became a star in San Francisco. In the late 1950s, his furniture showrooms were filled with glamorous vignettes, with key pieces from designers he admired, like Syrie Maugham.

Not long after Elkins’s death, he designed a bedroom for the Schlesingers’ daughter, Nan — later, Nan Kempner, a legendary socialite and fashion icon — in her parents’ home. The space’s low-key, green and white decor, which deferred to its sweeping view of San Francisco Bay, was typical of the California Look’s embrace of the Bay Area’s natural beauty.

For the light-filled, high-ceilinged living room of the Pacific Heights home of architect Sandy Walker and his wife, Pat — which Taylor completed in 1970 and Lyon shot for House & Garden — the designer selected several of his signature pieces: a wicker armchair, an antler chair, Mexican tin tables and a plaster lamp. To these, he added a woven-leather stool, a classical bust and a casual slip-covered sofa.

In 1970, Taylor did the interiors of a house in San Francisco’s Pacific Heights neighborhood that young modernist architect John “Sandy” Walker had designed for himself and his wife. In the living room, a long horizontal painting by Kenneth Noland on one wall overlooks a diverse array of pieces, including a white-slipcovered sofa, wicker chairs, a horn chair and tin tables from Cost Plus. He was never afraid of mixing high and low, which was also typical of his California Look peer John Dickinson.

Taylor — who was as adept at creating colorful, antiques-filled rooms as he was at rugged neutral spaces — went on to design a line for Baker Furniture and remained an A-list decorator until his death, in 1986, at age 59.

In the late 1950s, Anthony Hail — a former employee of Taylor’s — became a top decorator to San Francisco’s elite. After studying architecture at Harvard and working with Edward Wormley, he developed a style that was classic and polished but still accessible. His graceful antique-filled rooms were anything but fussy.

A case in point is Guignécourt, the Hillsborough estate of art collectors Eleanor and Christian de Guigné III, where he combined antique and upholstered furniture in a way that was simultaneously impressive and inviting.

In the 1970s, John Dickinson emerged as San Francisco’s most daring designer. He became famous for his rule-breaking look, exhibited in his own converted firehouse in Pacific Heights. The home’s spacious living area featured a large Art Nouveau table — topped by tall dome-shaded lamps of his own design — and leather-covered Victorian chairs. The dressing room had closet doors shaped like scaled-down architectural facades.

Dickinson’s home captured just the kind of unconventional elegance that has characterized the California Look from the beginning, and that we can still learn from today. Lyon’s decades’ worth of photographs — and now this new book — show it all off with remarkable clarity.