Although she doesn’t have the name recognition of Syrie Maugham or Elsie de Wolfe, Frances Elkins (1888-1953) was one of the most prominent grand-dame decorators of the first half of the 20th century, and arguably the most influential on the West Coast.

A portrait of Frances Elkins.

Born into a prosperous Milwaukee family in the clothing business, Frances Elkins, née Adler, might never have ventured outside of Wisconsin were it not for her older brother David. After graduating from Princeton, he decided to tour Europe and study architecture there, and he brought his teenage sister along. Together, the siblings explored the castles, cathedrals and great manor houses of France, Germany and Italy. And in Paris, they ventured into the studios and garrets of the city’s avant-garde artists and designers. The experience was life-changing. Adler was deeply inspired by the classical architecture he saw, while his sister was captivated by the future-looking art they encountered.

After three years abroad, Elkins returned to the States. In 1917, she married Felton Broomall Elkins, a wealthy Philadelphia–born playwright and polo player who took her to live by the sea in Monterey, California, where many of their society friends were building houses in nearby Pebble Beach. The couple bought a derelict 19th-century adobe mansion, Casa Amesti, that Elkins planned to renovate with her brother, who had established an architecture practice in Chicago designing stately homes. The young marrieds spent $5,000 on the house, which their local friends joked was about $5,000 too much. But Elkins insisted it would be the most attractive home in northern California when she and her brother were done.

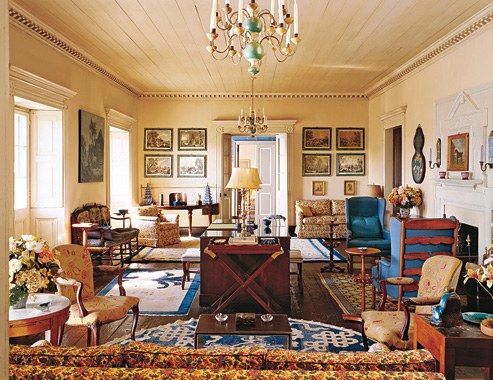

The drawing room at Casa Amesti, designed by Elkins.

Collaborating formally for the first time, the siblings immediately demonstrated a genius for crafting interiors that were at once timeless and timely. Adler understood just how to mix architectural languages to create spaces of drama and interest. Here, he juxtaposed a classical vocabulary of dentil cornices, fluted door casings, and, in the living room, a pedimented over mantle against the adobe’s thick plastered walls, wide-planked ceilings and redwood flooring. Rather than look awkward or forced, these adeptly added formal elements gave the spaces the balance and proportion they had previously lacked.

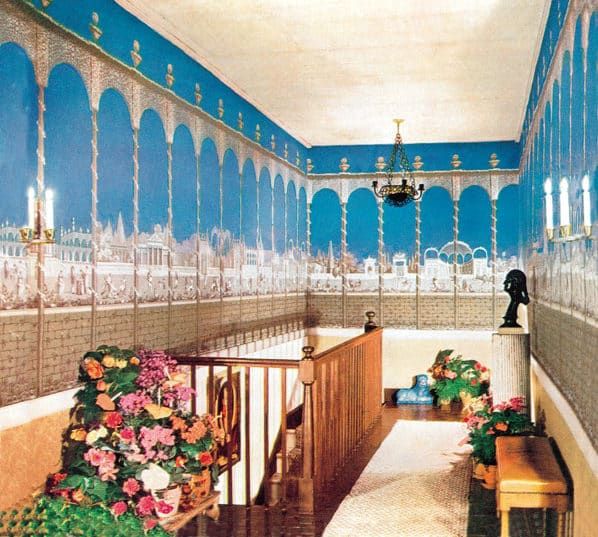

The second floor landing at Casa Amesti.

Elkins, meanwhile, enlivened the rooms with a decorative mélange of French and English period furnishings along with Chinoiserie, all within a brilliant color scheme of yellow, blue and white, and arranged in the symmetrical settings her brother favored. When they were finished, Elkins was proved right — Casa Amesti was unlike any other home in northern California. It was fresh and sophisticated, warm and inviting. As soon as they saw it, Elkins’s friends all wanted something like it for themselves.

This was likely Elkins plan all along, but it was also exceedingly fortunate: Her marriage had crumbled and she now had three small children to support. One of her first commissions was decorating the Monterey Colonial of her good friend Hester Griffin. For the living room, Elkins selected Chippendale furniture, Queen Anne mirrors and Ming screens in a stylish palette of bone and black. To give the space a contemporary twist, she added very new and daring lamps by Jean-Michel Frank and covered the scoop-back sofa and armchairs with peach corduroy, a material which was plush yet utterly unconventional as a furniture covering. It started a trend.

Throughout the 1920s, Elkins decorated a host of other houses around Pebble Beach. In truth, though, her efforts went beyond decoration, as she also taught her clients how to live stylishly. She told them how tables should be set and how flowers should be arranged. Her local work culminated with her design of what was to become the legendary golf club, Cypress Point. She decorated the clubhouse interior in tones of beige, yellow and melon and furnished the rooms with French provincial pieces, creating spaces that were gracious yet informal. For all her love of the new, she was quite partial to this furniture style and used similar pieces in several projects on which she teamed with her brother along Chicago’s North Shore during the late 1920s and 1930s.

The drawing room of the Wheeler House in Lake Forest, IL. A set of Elkins’ Loop chairs are arranged around the games table.

The siblings went on several buying trips to Europe during this time. A savvy businesswoman, Elkins recognized commercial opportunities when she saw them, and so became the first American importer of French country antiques, as well as the sole distributor of the furnishings of Jean-Michel Frank and Alberto Giacometti in the States. She became quite friendly with both these major talents and collaborated with them on several designs. Eventually, she opened her own workshop, where a staff of artisans reproduced favorite furnishings, lighting and accessories, in addition to realizing her own designs. Ironically, the Loop chair for which she is best known is an 18th-century design, which she reproduced only twice for the “living porch” of Mrs. Marshall Field on Long Island and the living room of the Wheeler house in the Chicago suburbs.

Working together brought out the best in each of these two, thanks to the aesthetic push and pull of Adler’s rigorous classicism and Elkin’s adventurous modernity. Elkins would always add an unexpected element or two into her brother’s formal interior architecture, such as a snaking metal inlay on a dark wood floor or Steuben glass moldings around a mantle piece. And where she could, she’d insert into settings of period furniture a sofa or lacquered table by Frank or a plaster lamp by Giacometti.

The entrance to the Reed House in Lake Forest, IL.

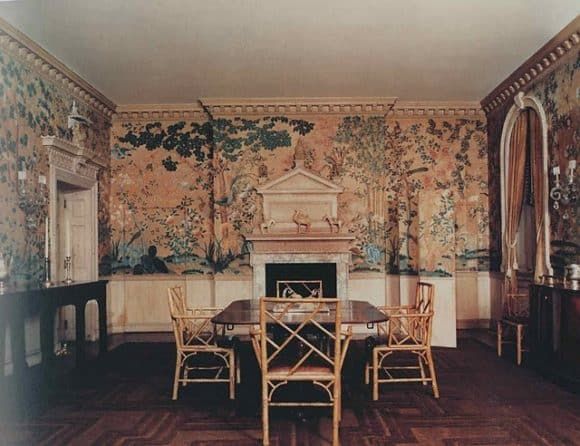

Classic and modern combine in witty ways in one of the duo’s greatest achievements, the Lake Forest home of Mrs. Kersey Coates Reed, completed in 1931. Adler built the grand Pennsylvania German-style house out of sparkling gray mica, and he and Elkins packed its elegant interiors with sumptuous antiques, including parquet flooring from the château of Madame du Barry. Typical of their original approach, they composed a regal entrance hall, while creating adjoining Art Deco powder and cloak rooms.

The dining room of the Reed House.

For the library, which featured an imported pine-carved mantel, doors and casings, Elkins took inspiration from Frank, covering the walls with panels of beige Hermès goatskin and wrapping the volumes on the shelves in parchment with cutouts to expose the titles. The furniture she selected included an antique English games table, Queen Anne chairs, along with a Frank sofa and club chair. The interior designer Mark Hampton later deemed it “the most stylish room I have ever seen in this country.”

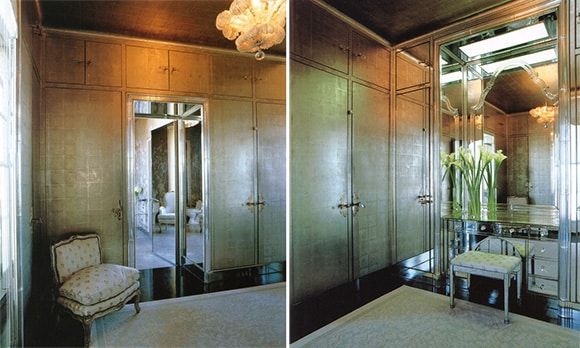

Two views of the mirrored dressing room that Elkins designed for the San Francisco home of J.D. Zellerbach.

By the Thirties, Elkins was working frequently in San Francisco, decorating interiors for some the city’s most prominent families, as well as designing a number of commercial projects, including the Yerba Buena Club for Women. Again, her approach was eclectic and bold. She renewed the club’s waiting room and lounge, by covering the Victorian-style seating in audacious reds and blues. And while she paid tribute to Frank in the design of the minimalist dining room’s staircase, seating and torchieres, she also splashed it with color by covering the walls in yellow velvet. Among her host of impressive residential commissions in San Francisco, perhaps none is famously the J.D. Zellerbach residence. The most famous room in that stunning home might be its glamorous Art Deco mirrored dressing room.

Despite her brother’s disapproval, she also decorated houses for several Hollywood figures, including the producer David O. Selznick and Edward G. Robinson, who in stark contrast to his gangster roles, might have been Los Angeles’s most cultured man.

Edward G. Robinson’s Beverly Hills living room.

Known by the 1930s as a doyenne of design, she dressed the part, wearing a uniform of Mainbocher outfits and traveling to appointments in a chauffeur-driven car. On the three-hour drives to the city from Casa Amesti, which she remained her sole residence, her maid would pack her a hamper of snacks along with a bottle of chilled champagne. Her bon vivant lifestyle no doubt impressed her well-heeled clients.

Sadly, Elkins and her brother both died relatively young in their mid-sixties. Yet not before contributing significantly to what would become cosmopolitan American style. The eclectic mix of modern and traditional that still prevails today as sophisticated decor owes much to their original invention.