June 22, 2015The 1914 composition Electric Prisms, featured in “Sonia Delaunay,” currently at London’s Tate Modern, embodies the artist’s signature use of interlocking planes of dynamic color. Top: A detail from Delaunay’s Rhythm Color No. 1076, 1939. Photos © Pracusa 2014083

For as long as I’ve been writing about art, the Franco-Russian abstractionist Sonia Delaunay has seemed to be a classic example of the perpetually under-recognized female artist. She played a pioneering role in the early-20th-century avant garde, yet she has never quite gotten her due. This is partly because her most admired achievements were in fashion and textile design, making them easier to dismiss. In addition, many of the advances she made in the field of chromatic abstraction were done in collaboration with her husband, the French painter Robert Delaunay; together, the couple originated the lyrical Cubo-Futurist offshoot known as Orphism, which was inspired by Simultanism, a branch of color theory that aimed to set color free, weaving it into everyday life by shaping it with light, rhythm and movement.

After Robert’s untimely death from cancer in 1941, Sonia devoted herself to promoting his work, rather than her own. Previous exhibitions have tended to show her oeuvre alongside his, or to focus primarily on her textiles, as in “Color Moves: Art and Fashion by Sonia Delaunay,” which New York’s Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum mounted in 2011.

Delaunay was celebrated for her colorful, geometrically abstract textiles and fabrics, like this coat of brown, camel and rusty-red rectangles she created for American actress Gloria Swanson. Photo © Pracusa 2014083

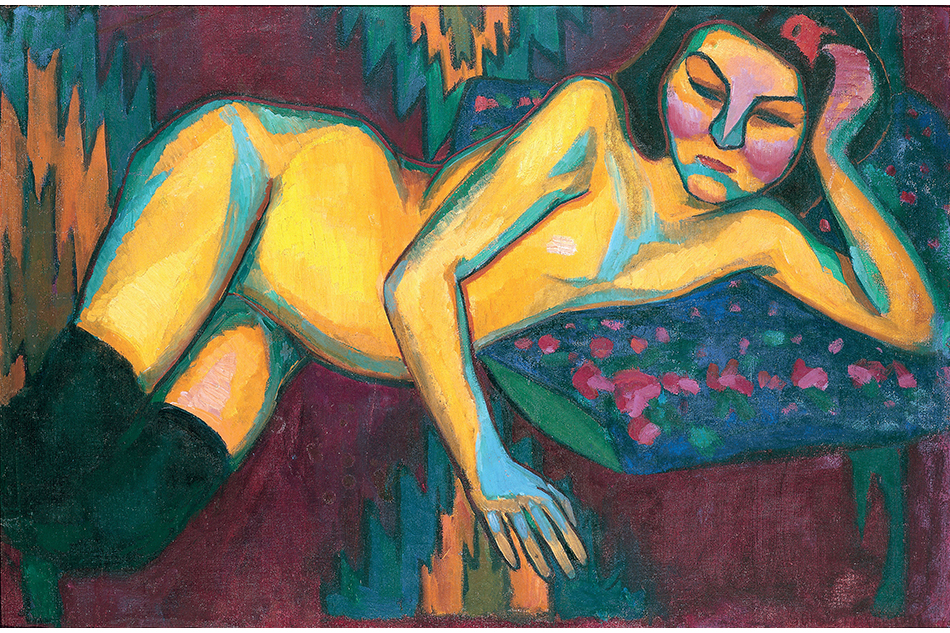

But all these stumbling blocks are overturned by the revelations of “Sonia Delaunay,” at Tate Modern in London through August 9. Co-curated with the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, where it debuted last fall, it is the artist’s first full-scale retrospective since 1980, the year after her death. And it seems to cover everything: not just abstract paintings and textiles and fashion designs, but also Delaunay’s early, sensual portraits and nudes; her monumental murals of abstracted people and machines, made for the Paris International Exposition of 1937; 1950s and ’60s designs for mosaics and rugs; and several decades’ worth of her collaborations with the likes of Sergei Diaghilev, Jean Arp and, of course, her husband, Robert. In the process, the show suggests that Delaunay’s work also presaged many other avant-garde movements, such as kinetic art, Op Art and performance.

“The aim of this exhibition was to encompass all her practice,” says Juliette Rizzie, a Tate curator who worked on the show. “She did so many different things throughout her life.” Curiously, for an artist who dedicated herself completely to pursuing dynamic abstraction, that life was marked by change from the start. Born Sara Stern to a poor family in Ukraine (then part of the Russian Empire) in 1885, Delaunay was adopted as a child by a wealthy uncle in St. Petersburg, renamed Sofia Terk and became known as Sonia. Her new family sent her to Germany at 18 to study art; she soon decamped for Paris. There, influenced by a brand-new group of painters, the Fauves, she painted portraits and nudes that married violent coloration with the woodblock-like outlining favored by Paul Gauguin. To avoid returning home, she married the homosexual German dealer William Uhde, who presented her first exhibition in 1908. Two years later, she left Uhde for the young painter who would become her husband, and together they developed Simultanism, a theory of pure abstraction based on the work of 19th-century chemist Michel-Eugène Chevreul, who studied how colors seem to change in relationship to each other.

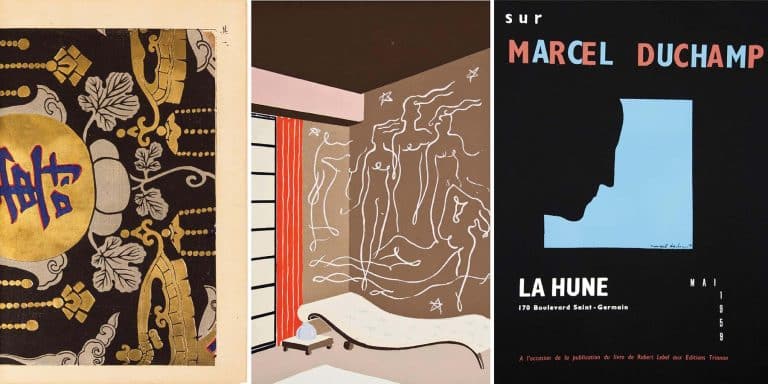

As her 1925 painting Simultaneous Dresses (The Three Women) demonstrates, Delaunay made no distinctions between creative genres, regarding everything from clothing to walls to floors as blank canvases for her designs. Photo © Pracusa 2014083

The couple generally expressed these ideas in their work with flat, overlapping panes of color. In fact, Delaunay’s first abstraction simultané was a cradle cover, made in 1911 for their son, which melded their tenets with the traditions of Russian-peasant patchwork (also a big Constructivist inspiration). Seeking to integrate Simultanism into all aspects of life, she designed other abstractly patterned furnishings for their home, which had become a gathering place for the avant garde, and she worked the designs into their clothes, too, which she and Robert would wear throughout the city and to dance halls — behavior that today would likely be described as performance.

Delaunay subsequently remade herself many times. After sitting out the First World War in Portugal and Spain, the couple received a frosty welcome from their old friends in Paris, so they took up with a group of Dadaists, including Tristan Tzara, instead. (In the early 1920s, Delaunay collaborated with him on a series of wonderful “dress-poems,” which melded words and color with movement; some of her preparatory drawings for these wearable works, themselves no longer in existence, are also in the show.) And when the Russian Revolution cut off Delaunay’s financial support, she reinvented herself as a designer, establishing a boutique where she sold clothes and household products.

Depicted in front of the “door-poem” she created in the Paris apartment she shared with husband and fellow artist Robert, Delaunay believed that art and life should not be separated. Photo courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale de France

In 1925, she launched a fashion house, Simultané, and soon after began designing textiles for an Amsterdam department store, a collaboration that lasted until the 1960s. She and Robert were also founding members of various 1930s associations that promoted abstract art, such as Abstraction-Création and Realités Nouvelles. Later, after Robert’s death and in an effort to burnish his memory, Delaunay began organizing exhibitions and mentoring young artists, often hanging their work alongside his.

Of course what’s also so appealing about Delaunay’s oeuvre, to contemporary eyes, is the sense that she pursued everything — be it painting or fashion or costuming or furniture or graphic design — with equal vigor, without making distinctions between mediums. And because the show includes material from all of Delaunay’s many periods and pursuits, and similarly casts distinctions aside, it becomes easier to see her Simultanist creations as she must have viewed them herself. One of the most spectacular galleries is dedicated to Delaunay’s textiles, some of which are displayed on a circuit of looping panels. Many clearly presage the work of the Op abstractionists to come, like Richard Anuskiewicz and Bridget Riley.

The show also includes a wonderful color film, made in 1925 to promote Delaunay’s “robes et tissus simultanés” (Simultanist dresses and fabrics). In one sequence, a model wearing a dress covered with orange and black rectangles stands on a stage, embracing an enormous color wheel that modulates from pale to dark blue. As she rotates this wheel, causing the color behind her skirt to shift, she presents a creative vision that appears at once completely of its time and totally timeless. It seems the perfect embodiment of Delaunay’s own dictum, expressed in her 1978 autobiography, Nous irons jusqu’au soleil (We Shall Go Up to the Sun): “Abstract art is only important,” she wrote, “if it is the endless rhythm where the very ancient and the distant future meet.”