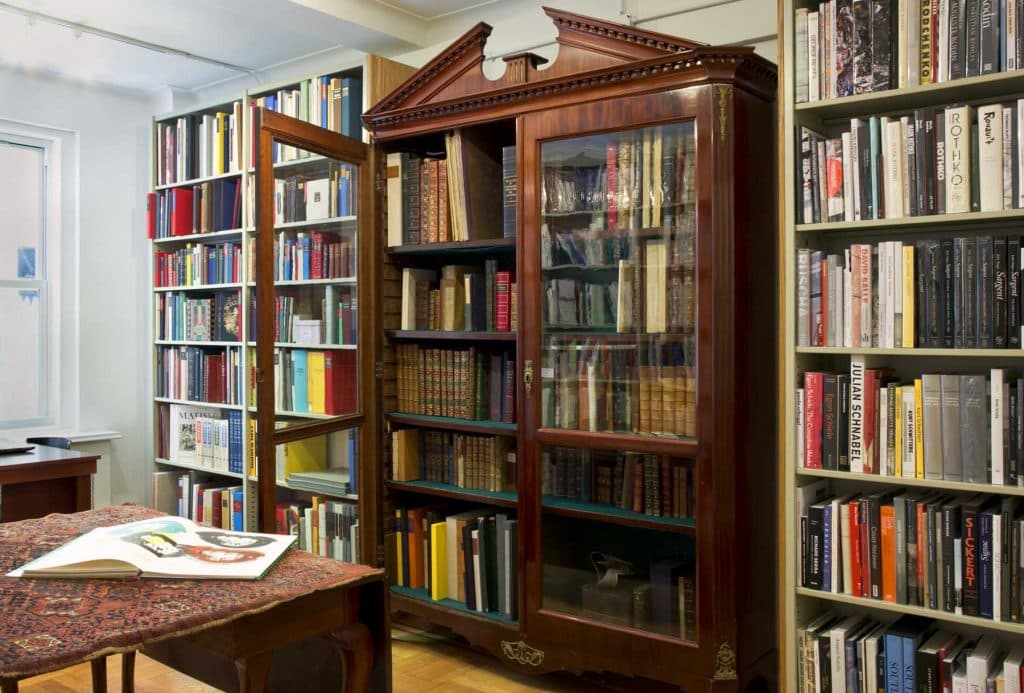

July 26, 2020The wonderful thing about books is that almost every subject has something written about it. You go back to the eighteenth century, for example, and there are literally thousands of books and pamphlets just on ballooning,” says Peter Kraus, of Ursus Books, a rare-book dealer on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. “All you need to start collecting books is curiosity and a passion.”

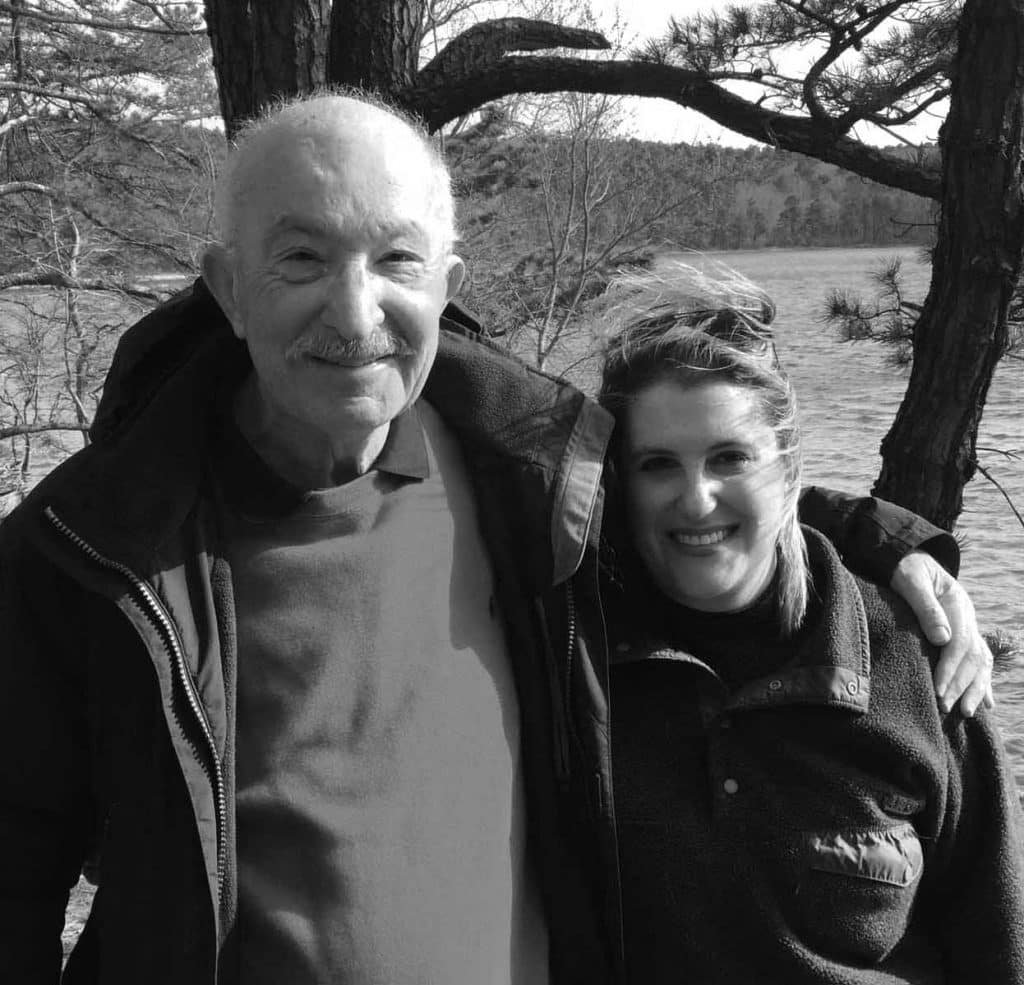

Ballooning enthusiasts may be in shorter supply today than in the 18th century, but Ursus has carved out a niche in a category with no shortage of passionate devotees: modern art. Kraus, who moved from England to New York in the 1960s at the age of 18 to apprentice in the rare-book trade with his uncle, the legendary H.P. Kraus, founded Ursus in 1972. Olivia Kraus, his daughter, joined the business in 2013.

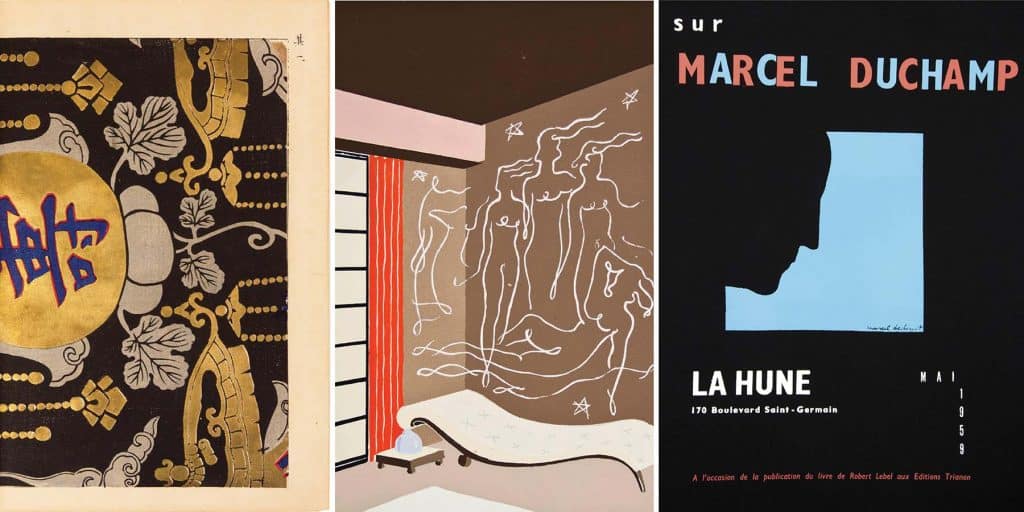

Although Ursus carries a wide range of rare printed matter, from antique educational materials to literary first editions, it specializes in illustrated books, with an emphasis on artists’ books made after 1900 — a category that includes volumes by some of history’s most creative and influential avant-garde minds, including Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol.

While such volumes, with their stunning plates and often fantastic pictures, certainly have a strong visual appeal, they exercise an attraction for Kraus that goes far beyond that: “The wonderful thing is you can sit and look at a wall of books, and it can take you into a whole other world the way other things don’t. You don’t even have to take a book off the shelf for it to speak to you. That’s part of the magic.”

Introspective caught up with Kraus to find out more about artists’ books, collecting trends and the hype behind first editions.

What led you to focus on illustrated books?

I was first interested in art, mostly medieval art — illumination books. I felt the need to specialize when the Internet came about. It became very important to stand out from the crowd. I chose illustration not just because it’s what I love the most but because illustrations are easy to digitize.

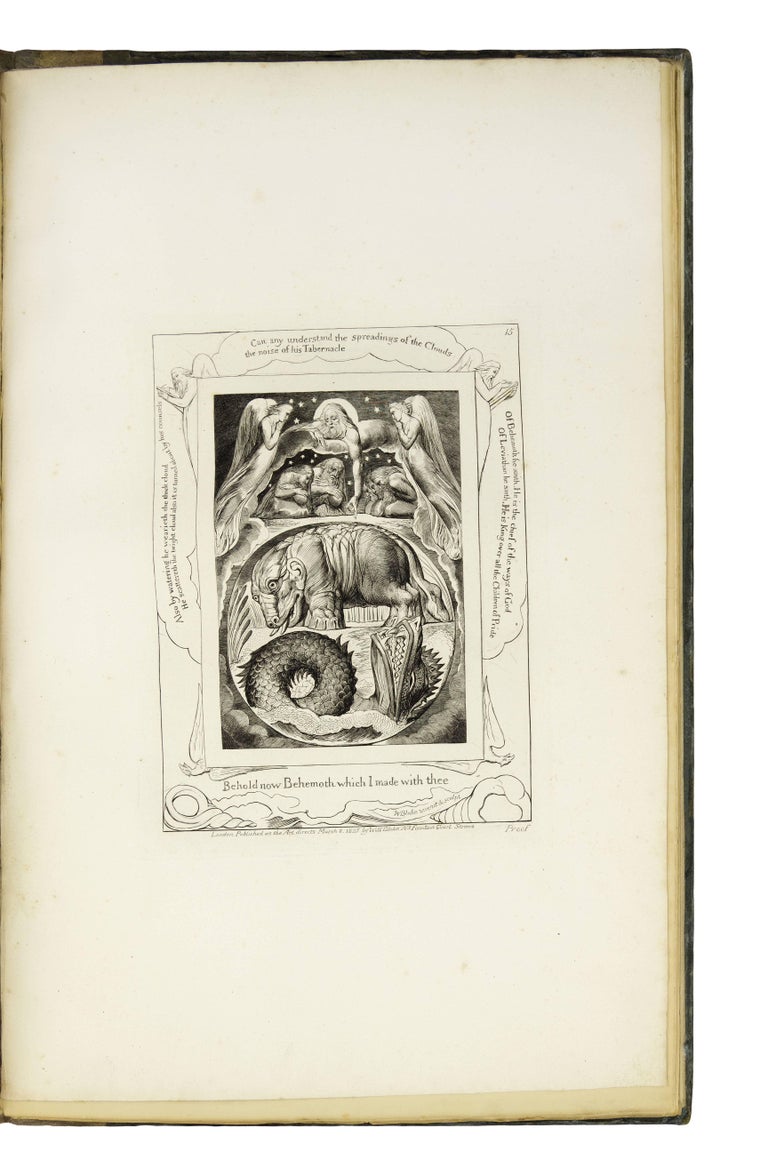

Granted, when you have the book in your hand, it’s a hundred percent different. The color, the detail, the texture — it has a physical presence. There is so much craftsmanship that goes into putting a book together.

Modern artists’ books are a particularly noteworthy niche of yours. Why are they so important?

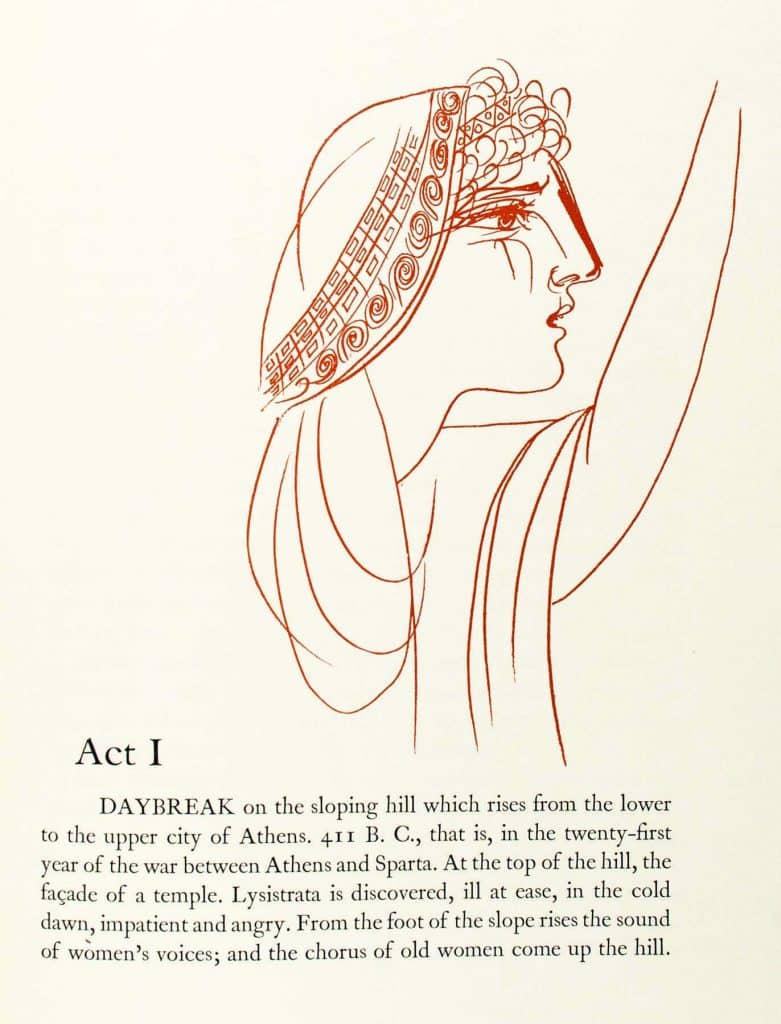

Numerous artists were obsessed with books, and twentieth-century illustrated books are a huge part of the story of modern art, which museums have come to realize too. Picasso made one hundred and fifty, Matisse almost fifty, Mirò close to a hundred.

Many, many artists have illustrated old literature — Picasso illustrated Aristophanes, for instance. But to me, it’s much more interesting when the artists are working together with their contemporaries. You can find Gertrude Stein illustrated by Juan Gris.

The greatest American illustrated book of the twentieth century is without a doubt Fizzles, in which Jasper Johns illustrates Samuel Beckett. You get a great artist and great writer working together, so it’s much more important than just the pictures.

There are so many extraordinary artists’ books. If you had to pick just one, which would it be?

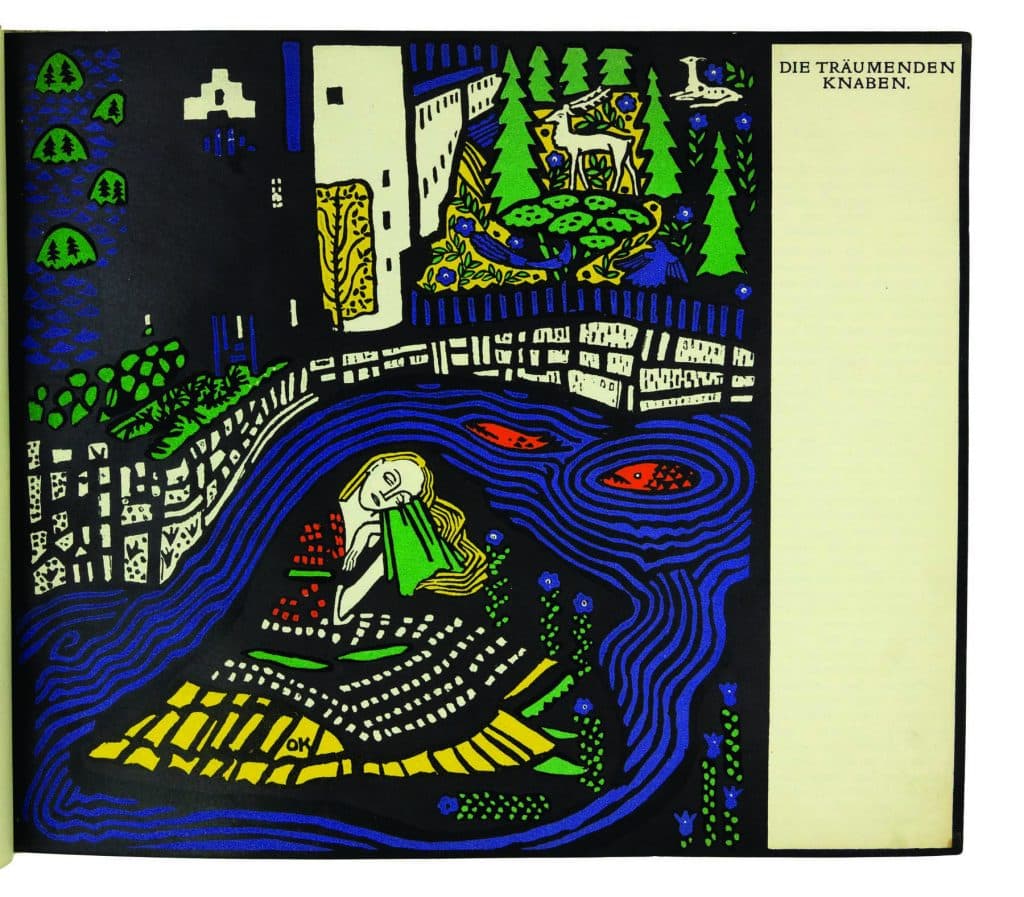

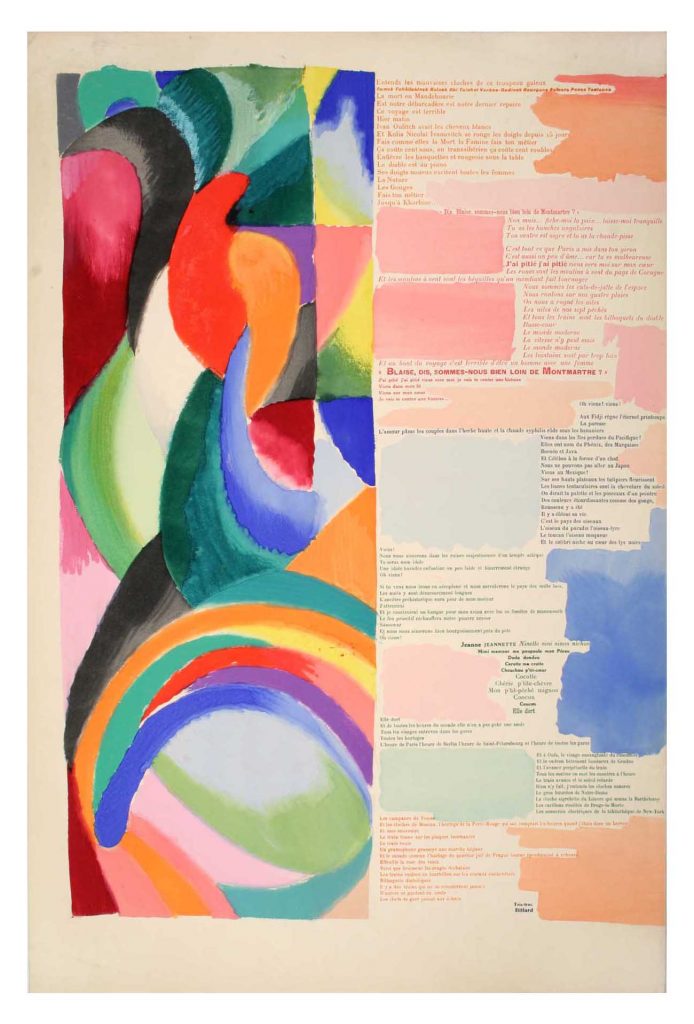

If I were on a desert island with only one book, I’d want La Prose du Transsibérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France (Prose of the Trans-Siberian and of the Little Joan of France), a collaboration between the artist Sonia Delaunay and the poet Blaise Cendrars published in 1913.

The edition was supposed to be two hundred fifty, but only sixty were done because of the war. It’s the most extraordinary object — a magical book. Delaunay handmade the cover with a painted vellum, and the hand coloring is dazzling. It’s teeny-weeny — maybe three inches by six — but it folds out to six feet.

Some examples have been unfolded and framed, and they’ve faded. But some have always been folded up, and those colors have never seen the light of day. It’s very avant-garde. And with the text by Cendrars, it’s an unbelievably of-the-moment book.

There are also some great contemporary artists’ books. Are they more affordable?

Yes, things like Ed Ruscha’s little books. They’re not limited editions, they’re not signed, they’re not on handmade paper, but they’re created by artists as a form of communication. Those books are very inexpensive, and young people seem to be especially attracted to them because they’re a way of owning contemporary art without being vastly wealthy.

What other categories should be on our radar?

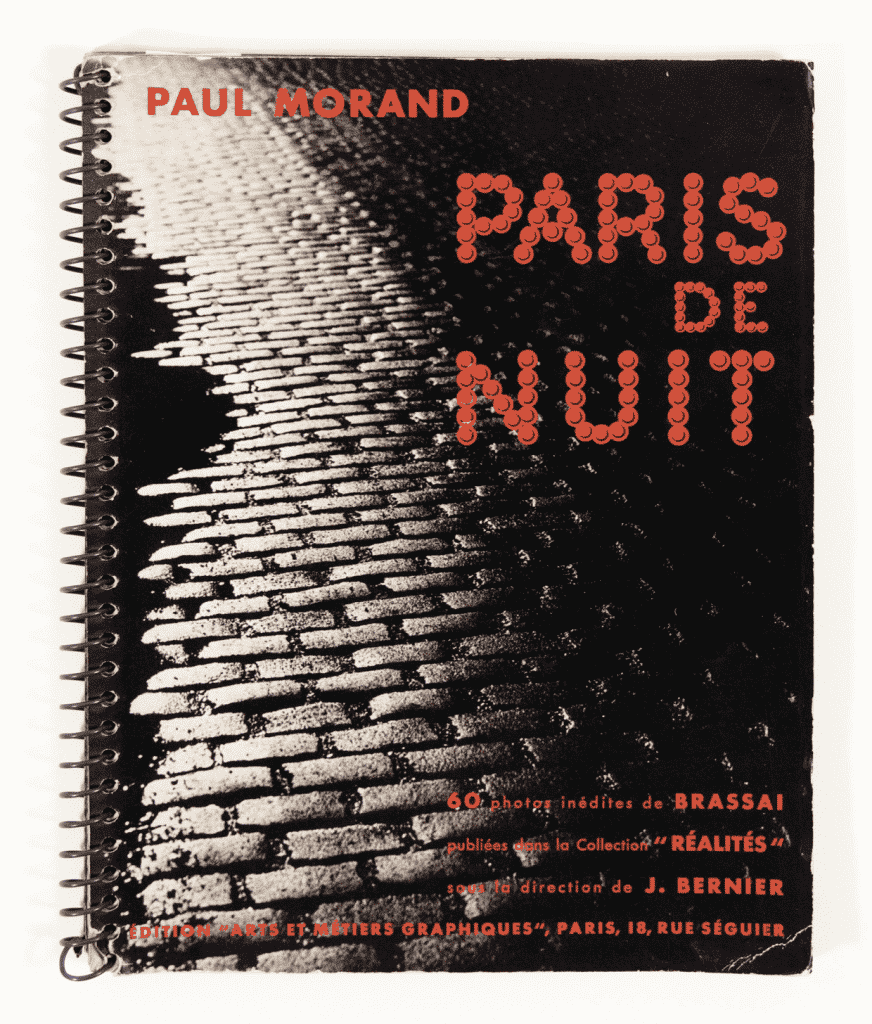

Guidebooks to cities and so on are one of my favorite categories. In the sixteenth century, they’d tell pilgrims how to find Rome and what they’d see when they got there, for instance. And they go right up to the present. In many cases, they recall information that is no longer around, towns that have disappeared or been destroyed. E.M. Forster wrote a guidebook to Alexandria before the First World War, and there’s one to Paris for which famous authors like Victor Hugo and Balzac wrote different articles.

Another subject that’s wide open for collecting is exhibition catalogues. The possibilities are endless, from the first exhibition catalogues of any artist — Van Gogh or whomever — to joint exhibitions of Surrealists or the exhibitions that Hitler had in Germany to display all the Degenerate art or the Armory Show catalogues. They take you right to the moment that the art was being made and discovered, and they are also very visually pleasing objects. And they are relatively inexpensive.

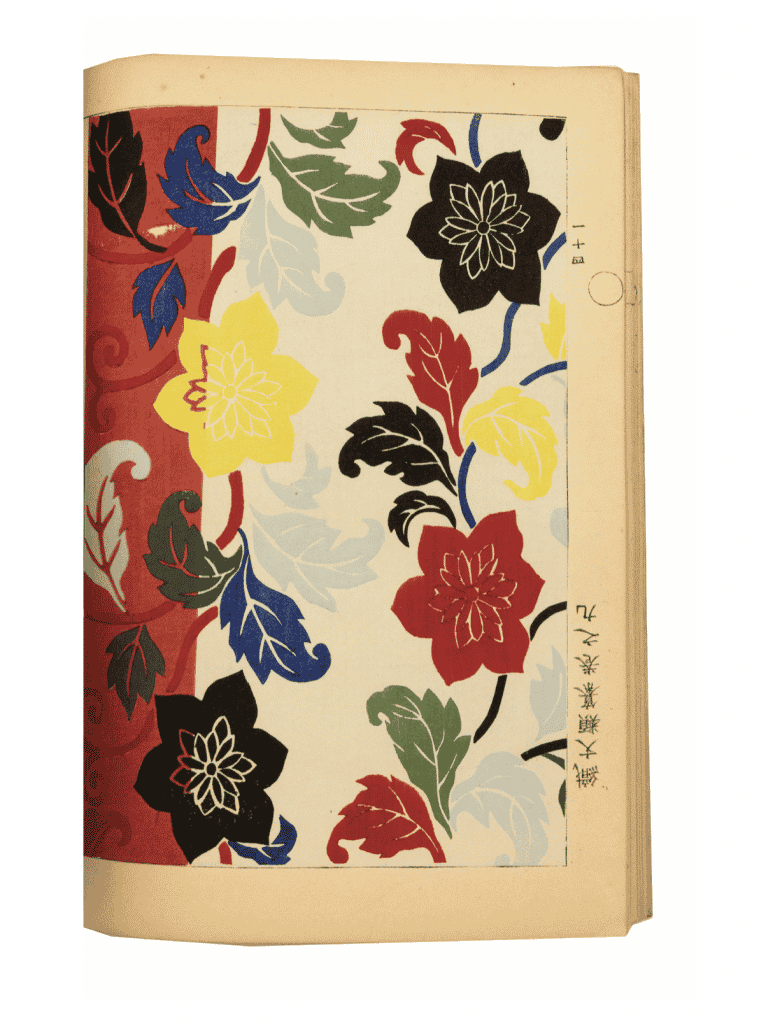

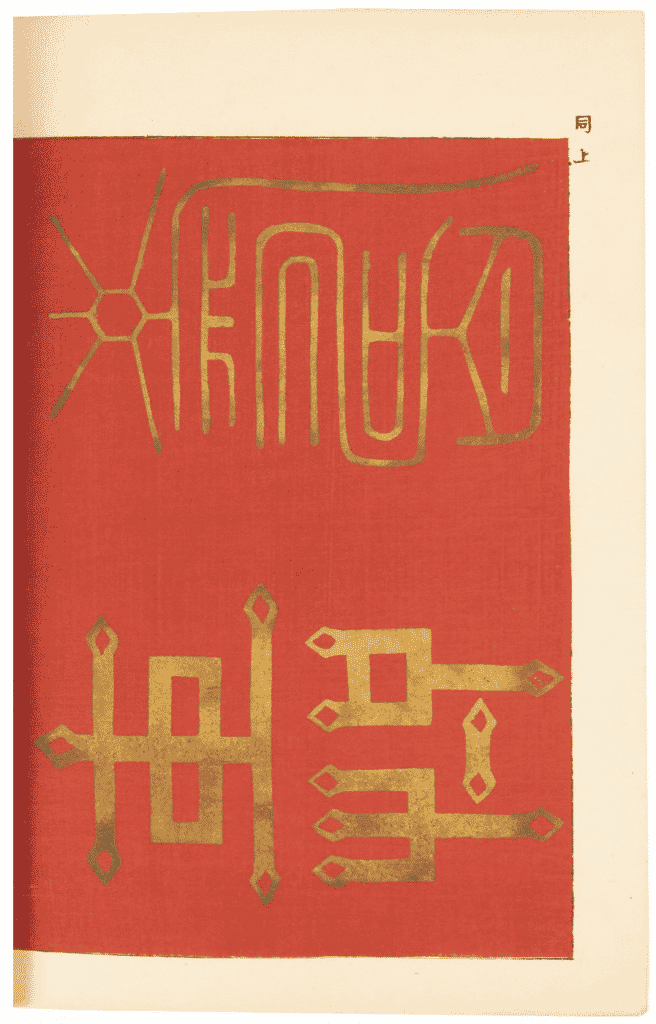

You also specialize in Japanese illustrated books. The plates in those books are exquisite. Were they made by artists?

They’re wood-cut prints. The craftsmanship is often extraordinary, the art is wonderful, and the price is ridiculously low. People can be put off by not speaking Japanese, but if you like Japanese art, they, like other illustrated books, can be a fantastic avenue into that world, and you don’t have to be a billionaire to collect them.

You hear a lot of talk in the book industry about first editions. Can you tell us why the term first edition is so meaningful?

With literature, first edition is everything. And with science, too. People love the idea that you are holding a copy of James Joyce’s Ulysses, the same kind of copy people held in 1922, when the book came out. Or Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls. It’s a way of making yourself somehow closer to the idea or the object.

Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species — the idea that you are holding the book that communicated this earth-shattering revelation to the planet is really exciting. Some are beautiful, but often it’s an ugly little pamphlet or book badly printed or bound. In many ways, that makes it even more magical.