November 8, 2020Most design lovers are familiar with Knoll, the manufacturer of furniture by Eero Saarinen, Harry Bertoia, Marcel Breuer, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and other modernist giants. It was founded by Hans Knoll in 1941 and led after his death by his wife, Florence Knoll, the doyenne of postwar American office interiors. In recent years, the company has added collections by Maya Lin, Rem Koolhaas, Frank Gehry and David Adjaye, among others, and encouraged customers to do what some of them had been doing all along: use Knoll’s “office furniture” at home.

Fewer Americans are familiar with Walter Knoll, the company Hans’s father founded in Stuttgart, Germany, in 1925 and later moved to nearby Herrenberg. That company has existed in the shadow of the larger U.S.-based Knoll for decades. But a new book, authorized by Walter Knoll’s CEO, Markus Benz, and written by publicist Bernd Polster, makes the case that it has “become an international player and risen to the pinnacle of its industry.”

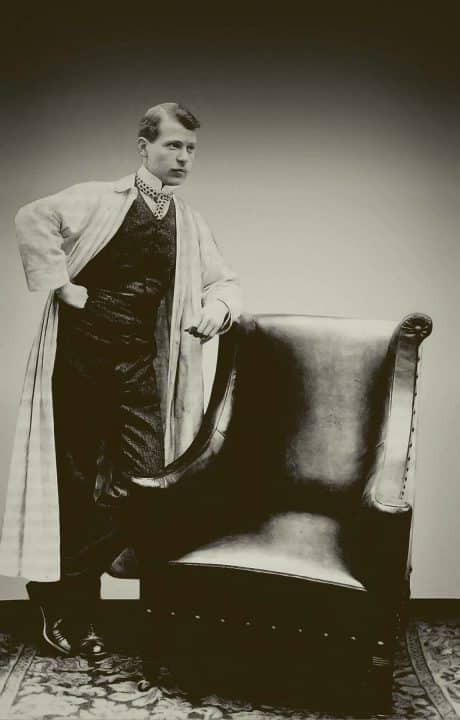

Both companies descended from the German manufacturer of ornate leather goods established by Wilhelm Knoll in 1866. In 1907, Wilhelm’s sons, Willy and Walter, took over the father’s business and started producing leather club chairs. Five years later, the company introduced its Nestra line of stripped-down wood and leather seating, foreshadowing the family’s future innovations.

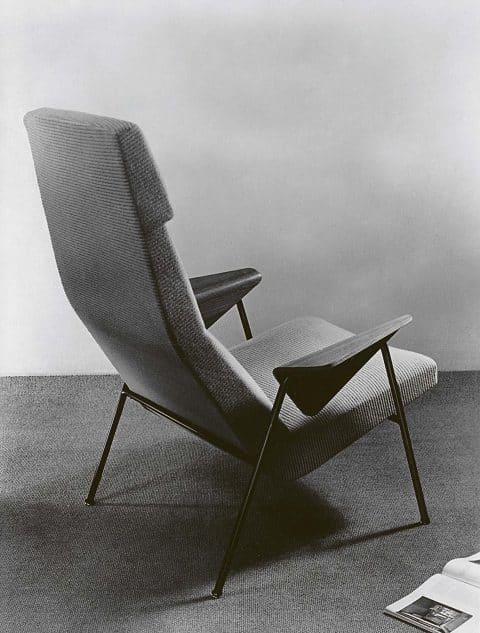

Inspired by the Bauhaus, founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius, Walter Knoll decided to bet big on modernism. In 1925, when he was 50, he launched the Walter Knoll Company, which soon released the revolutionary Prodomo line of chairs, whose upholstered seats and backs are supported by tubular metal frames. (Polster considers it the first modern upholstered furniture.) Other lightweight Walter Knoll pieces were used in the passenger compartment of the Hindenburg zeppelin.

In 1927, Walter Knoll furnished five apartments designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe for the Weissenhof Estate, 21 prototypes of “workers’ housing of the future” constructed as part of an exhibition in Stuttgart. A decade later, Walter’s son Hans, then 24, traveled to the United States to market his father’s furniture and to make a new life for himself in the New World. But inspired by his encounters with designers like the Danish-born Jens Risom, Hans broke away from Walter, creating Knoll Associates (now known simply as Knoll). The book, Polster observes, chronicles three generations of father-son conflicts.

Florence Schust (later to become Hans’s wife) joined him in the company in 1943, and soon they were working with Saarinen and Bertoia on new designs and licensing Mies’s Barcelona chair. As the Walter Knoll factories in Herrenberg were converted to wartime production, first of military furniture and then of aircraft, the American company flourished. Hans helped build a simulation of a German village for the U.S. Air Force, which used it to perfect techniques for firebombing residential neighborhoods in Germany. Polster isn’t kidding about father-son conflict.

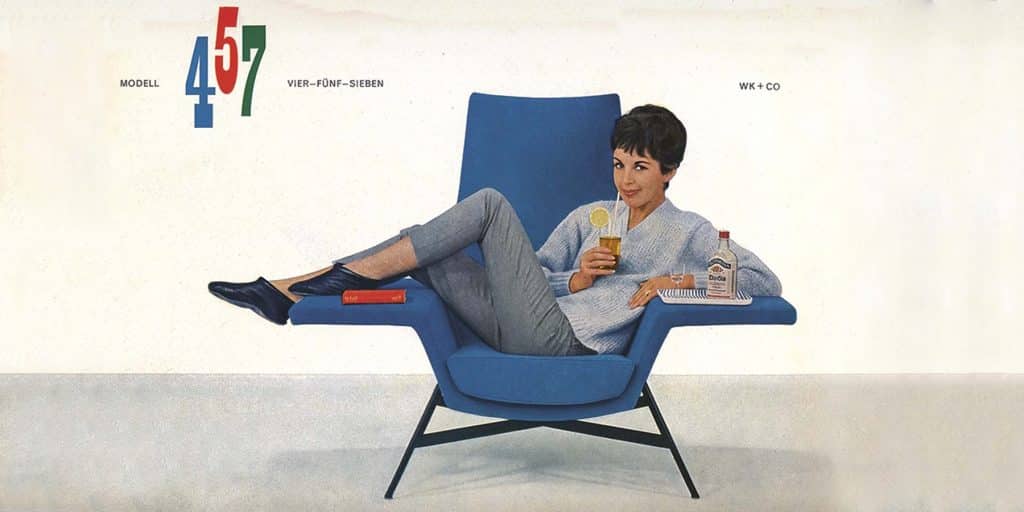

After the war, with his factories destroyed and labor and materials in short supply, Walter Knoll turned to Hans for help. Hans sent over several pieces from his Vostra line, designed by Risom. Walter replaced the web seats with upholstery and launched his version of the Vostra at the New Living exhibition in Cologne in 1949. It became hugely successful, persuading many Germans still accustomed to traditional furniture to give modernism a go. Hans Knoll died in a car crash in 1955, at age 41, ending the companies’ post-war collaboration. (Walter lived until 1971.)

Walter Knoll retired in 1964, but his namesake firm continued growing in Germany. In 1975, it furnished Berlin’s new Tegel Airport with its swoopy Berlin seating. After Germany reunited in 1990, the company took advantage of new opportunities. It manufactured furniture designed by Norman Foster for the British architect’s acclaimed reinvention of Berlin’s Reichstag. After the Reichstag reopened, in 1999, Foster worked with the German firm to design additional pieces, not only right-angled leather sofas and chairs but also a curved, modular seating system called Foster 620.

“I’ve worked with Walter Knoll for over two decades, starting with the furniture we designed together for the Reichstag in Berlin,” Foster wrote in an email. “Right from the outset we found a drive and appreciation of both craft and manufacturing, of how a combination of details will come together to create a whole.”

Just like the American Knoll, Walter Knoll has found that some customers want to use pieces originally meant as office furniture in their houses. In fact, these pieces give living and dining rooms a crispness that almost no residential furniture can match. And if some of Walter Knoll’s products look surprisingly like items sold by its American cousin, blame the two firms’ conjoined family tree.