May 25, 2025When the New York interior designer Randall Jones walks into a gallery, she assesses the offerings for a few moments — you can see the gears turning. Very quickly, she decides what she likes and, more importantly, how she would use a particular object.

She calls her design style “considered,” which is true enough, but it is also commanding, and it’s led her to early success as the founder of the residential and hospitality design firm Floret Studio, now five years old. In March, she won the 2025 Female Design Council Grant, sponsored by 1stDibs and industry star Nicole Hollis. Awarded to an outstanding designer of color, the grant comes with a cash prize and mentorship from Hollis, whom Jones praises for her “tactile and artful” work. “There is no substitute for learning the wisdom of those who’ve carved their path,” she adds.

That said, Jones is clear about her own taste. “I like poetry in a space, and I like for people to slow down and take things in,” she says, “so I’m all about things that resonate and provide intrigue.”

A graduate of Howard University, Jones got her MFA at Parsons School of Design, where she now teaches. She interned for Billy Cotton, known for his high-end residential projects and art-world clients, and then worked for the multidisciplinary design studio Yabu Pushelberg and the architectural powerhouse Rockwell Group before establishing her own firm.

Left: Juliana Vasconcellos’s Juta stools catch Jones’s eye at Bossa. Right: In the gallery’s annex, a 1950s chaise by Joaquim Tenreiro is accompanied by a 1950s floor lamp by Enrico Furio for Dominici and a contemporary vessel by Ilona Golovina.

Finding the right objects is a big part of the job, so she recently planned a spring sourcing trip to three 1stDibs dealers, beginning with Brazilian design specialist Bossa Furniture, in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood.

Bossa, founded by the Brazilian architect Isabela Milagre in 2017, has a space for contemporary works and an annex across the street for historical shows. On the day of Jones’s visit, Bossa’s main space is relatively empty as the staff is about to install a show of work by São Paulo–based designer Lucas Recchia. They invite Jones to play around with configurations of objects by Recchia and others to create some living room vignettes. She doesn’t need to be asked twice.

Recchia’s bronze candlesticks with bulbous bases shaped something like clogs especially catch her eye. “I love organic forms and asymmetry,” she says, putting two of them on Recchia’s Material Distortion table, a bronze-and-glass creation that evokes a stained-glass window. They look just so in front of his long, curving Eche sofa, upholstered in gray mohair.

These are the types of pieces that are catnip for “our extremely picky clients,” Milagre says, noting that 1stDibs buyers are among the very pickiest of all. “They want something extraordinary.”

Extraordinary things are also on display in the annex exhibition of furniture by the artist and designer Joaquim Tenreiro (1906–92), known as the father of Brazilian modernism.

Once they get talking, Milagre and Jones have an instant mind meld. “She’s so warm,” Jones says of Milagre, but the comment could apply to the rich, dark tones of the wood in the Tenreiro works too. “Ashier tones are trending, so this makes a nice balance,” Jones notes. As for the fabric Milagre put on Tenreiro’s 1950s chaise, “I love that she chose a blue mohair,” says Jones.

The designer’s interest is also held by Tenreiro’s 1950s Manta Solta sofa and set of armchairs in peroba de campos wood and black leather, which Milagre placed in front of a large bookcase of the same wood from the same era.

The sofa holds new pillows designed by Bossa with a beguilingly smooth texture — amazingly, the pillow covers are made from the skin of the pirarucu fish. The species, native to the Amazon, is eaten by locals, and the leathery skins, formerly discarded, are now sustainably harvested. Jones is fascinated by the combination of the pillow with the mid-century pieces. “I love mixing old and new like this,” she says.

Her next stop couldn’t be more different: Olde Good Things, the long-serving architectural salvage and antiques shop in Midtown West. Right away, Jones sees an elaborately carved 19th-century mahogany mantel with round, griffin-supported shelves on each side.

The piece would be too retro Victorian for many contemporary designers, but Jones sees the possibilities. “I was thinking about how I would style it,” she says. “I’d put a lamp on this side. It just needs to be freshened up.”

Turns out that Jones grew up in a Victorian house in the Hyde Park neighborhood of Chicago’s South Side. “That’s where my joy in historic homes comes from,” she says.

At Olde Good Things, finding a lamp for that mantel won’t be a problem, given that lighting is a specialty and thousands of objects are arrayed on any given day. Jones riffles through drawers of antique doorknobs, examines brass-encased nautical light fixtures and goes gaga for an old wooden file cabinet with dozens of drawers. The cabinet rotates, and she gives it a spin. “I’d put it in the center of a room,” she says. “You could put anything in there.”

The huge number of items in the shop does not throw her. “I like that it’s not too curated,” she says. “It’s all here. It’s up to you to select.”

Jones also likes a bargain, which is a strong suit for Olde Good Things, says store manager Jim DiGiacoma, who calls their price points “cool and comfortable.”

Designers like Jones once made up the bulk of his customers, but now 1stDibs and the power of Instagram have changed that. “We used to be more to the trade, but now it’s tilted the other way, to the public,” DiGiacoma says. He and Jones discuss a few choice items, notably a 1980s glass chandelier shaped like a large flower, before Jones is off to her next shopping stop, Galerie Philia’s elegant penthouse space in Tribeca.

Philia, established in 2015, also has branches in Geneva, Mexico City and Singapore. The gallery specializes in contemporary design and works with both established studios, like American Rick Owens, and with emerging talents, like Niclas Wolf of Germany and Andrés Monnier of Mexico.

“I love the selection here — it’s one of the most expansive I’ve seen from a gallery,” says Jones, adding that the owners have something of a gift for identifying talent. “They seem to have a really good intuition.”

Jones enters a loft-like space (one of several rooms in what is essentially a grand, two-story apartment) anchored by Dooq’s sculptural Malibu sofa, over which hangs Jérôme Pereira’s Planck lighting fixture, made of blown glass and oak. On the walls are striking black-and-white artworks by Fino Prydz, a Norwegian artist based in New York.

With an invitation from Philia to play around a bit, Jones decides to position a Daté Kan stone candleholder by Dan Yeffet for Okurayama Studio atop a Duramen brass-and-walnut side table by Jules Lobgeois. She tries a Rick Owens bronze Swan Neck vase in a few places before setting one atop Kar’s fiberglass Black Tripod coffee table.

The striking arrangements have a touch of the “theatrical,” Jones says, which also might work for a hospitality project, though that same energy could be used to enliven a home. “I like when hospitality can lean toward residential and vice versa,” she adds. “The blurring of those lines is one of the most exciting things about design for me.”

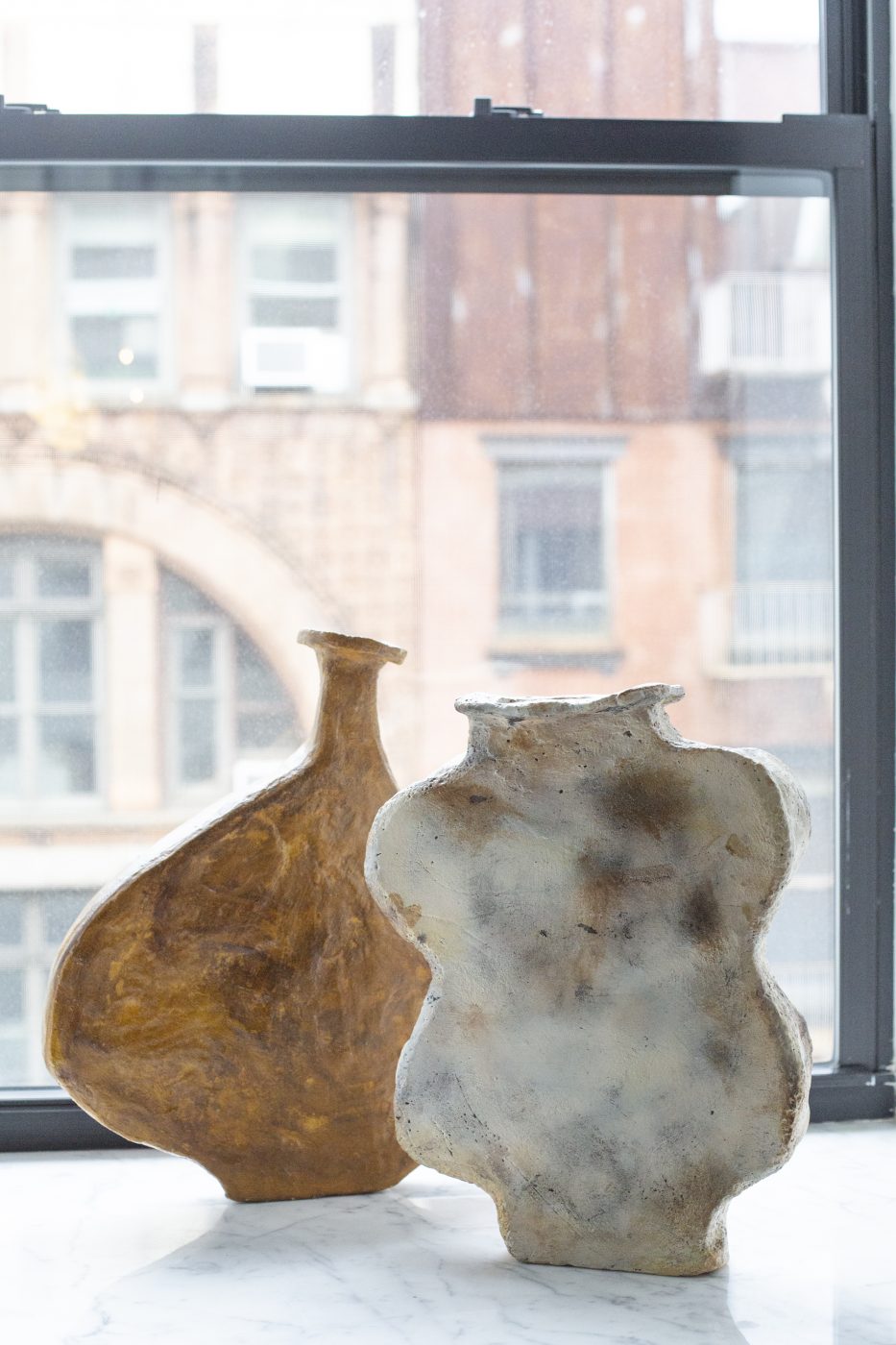

Philia’s selection of ceramic works — by artists including Laura Pasquino, Willem van Hooff and Jojo Corväiá — brings a human touch and softens up some of the sleeker, more contemporary materials. “I like to warm things up, and I love to see the hand work of ceramics,” says Jones.

Surveying her arrangement in progress, Jones appears pleased that she trusted her instincts. “Yes,” she says of a grouping that seems to invite people in. “This is starting to feel nice. You could have a conversation here.”