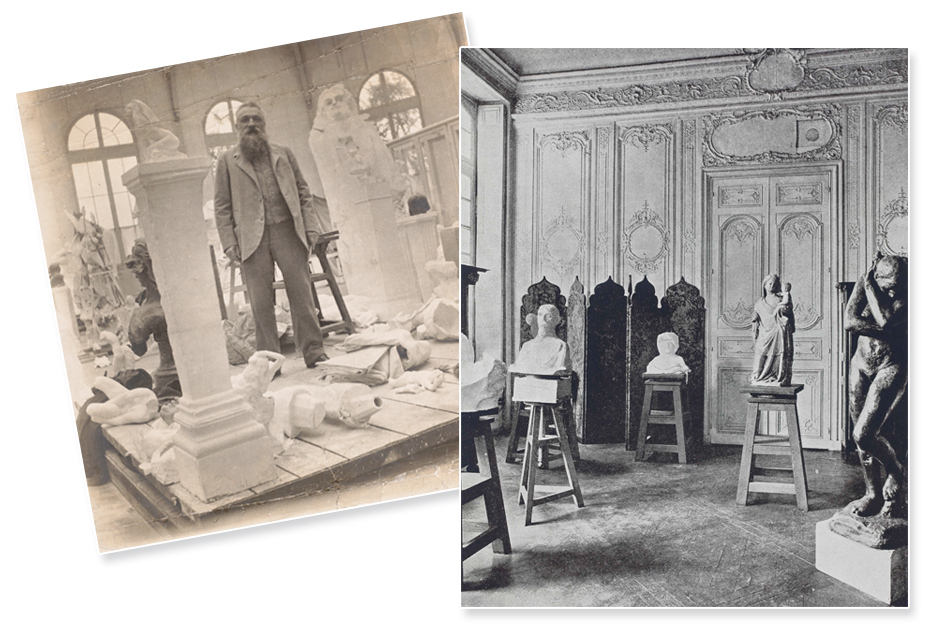

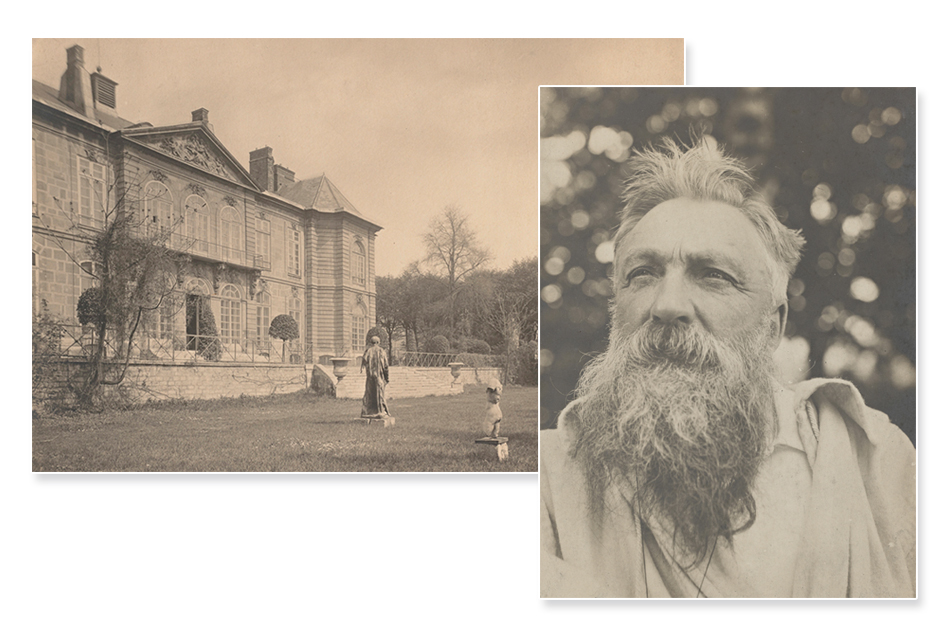

The 18th-century Hôtel Biron once served as Auguste Rodin’s exhibition hall and occasional studio in Paris. Today it houses the newly renovated Musée Rodin. Top: A second-story room holds plinths that were specially designed to support sculptures in the collection, such as Camille Claudel’s Vertumnus and Pomona, 1905 (far right). All photos © Musée Rodin, unless otherwise noted. Top: Photo by Jérôme Manoukian

November 16, 2015You don’t come to a museum to read — you come to see,” Catherine Chevillot told a group of international press on a recent preview of Paris’s revamped Musée Rodin. “I hate museums that start with a room full of text, so here, as you will discover, there are no wall texts in the galleries.”

It was an unexpected opening statement for a museum director — especially for the director of a historical institution dedicated to the life and work of Auguste Rodin (1840–1917), widely considered the forefather of modern sculpture — and it offered an apt introduction to the surprises awaiting inside the institution’s entirely retooled main building, which reopened on November 12 after three years of extensive renovation. Despite the absence of writing on the walls, Chevillot noted, viewers can find an abundance of educational materials elsewhere in the museum.

Located just south of the River Seine behind the Invalides, the Musée Rodin was founded in 1919, two years after the renowned French sculptor’s death. Although he was based primarily in the neighboring town of Meudon, he officially donated all his works and his personal collection of art and antiques to the French state and asked that a museum be created under his name in the Hôtel Biron, an 18th-century palace in Paris that he used as an exhibition space and occasional studio during the last years of his life. Up until this recent renovation, however, the majestic two-story residence had not been touched since his tenure there, and beyond its lack of the necessary amenities expected of a modern museum — restrooms and an elevator, for example — the building had fallen into disrepair.

Works are grouped under the thematic title “Emergence of a Sculptor,” in the gallery that examines Rodin’s entrance into the mature phase of his career. When the artist first displayed The Age of Bronze, 1875–77 (left), in Brussels in 1877, scandalized spectators claimed that the statue had been cast from a live man. Photo by Jérôme Manoukian

The structure’s rebirth, which coincides with the sculptor’s 175th birthday and was overseen by Dominique Brard, of design firm Atelier de l’Île, promises new life for the works on view inside it, many of which have never been seen by the public, despite the fact that they reveal essential aspects of the artist’s process. Displayed atop specially designed oak pedestals modeled on the work stools that Rodin himself used to both create and exhibit in the studio, a selection of some 200 sculptures, maquettes and plaster casts are arranged throughout the galleries so that viewers can circulate around them. “Rodin’s work is about his materials, and that includes the reflections, the gestures, the volumes,” Chevillot said. “Vitrines often create too much of a screen between the visitor and the work, so we avoided them.”

The Hôtel Biron’s original flooring and panel parquets were entirely restored, as were its ornate wooden cornices and the damaged panes of its ample windows, which look out on a world-famous sculpture garden that includes some of the artist’s chefs d’oeuvre, including The Gates of Hell (modeled 1880–1917, cast 1926–28) and The Burghers of Calais (modeled 1884–95, cast 1919–21).

Since many of the rooms are flooded with natural light, a high-tech system adjusts the illumination according to the time of day and the season. Then there are the wall colors. “We found a sort of light green on the walls when we restored them, but we also wanted to use a second wall paint with the right intensity,” Brard explained, so the British paint experts Farrow & Ball created a special color, Biron Gray, to “bring out all of the materials Rodin worked in, from marble to stone or even the dark shade of bronze.”

Museumgoers can get up close and personal with The Kiss, 1882–89. Photo by Jérôme Manoukian

“We wanted the museum to feel like a home, because it used to be a home,” he added, noting that 60 paintings and sculptures from Rodin’s multifaceted personal collection — which included Greek and Roman sculptures, 15th-century Japanese antiques and paintings by such contemporaries as Vincent van Gogh and Claude Monet — have been hung along hallways and staircases as they would have been during his time. “The challenge was to preserve the magic of the historic hotel, while making it feel alive and new.”

The museum’s grand foyer has been newly inaugurated as Cantor Hall, celebrating the museum’s longtime collaborators and benefactors Iris and Bernard Gerald Cantor, who assembled the world’s largest private collection of Rodins over the course of six decades and whose donation of $2 million to the institution marks its first private funding. “When I met Bernie, I realized very quickly that if I didn’t love Rodin, then I couldn’t love Bernie,” Iris says of her late husband. “When he died in 1996, he left such a great legacy that it had to be continued, so I consider myself the guardian of this collection.”

The marble sculpture that began Bernard’s obsession with Rodin — The Hand of God (modeled ca. 1896, executed 1907), which the collector first saw at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in the 1940s — is placed underneath the dedication. “Everything comes full circle for me with this hall,” Iris says. “It’s a great honor, and I’m sure both Rodin and Bernie are smiling.”