March 12, 2018A new book on Christo and Jeanne-Claude — partners in life as well as art until the latter’s death in 2009 — tracks the development and execution of their signature building-wrapping public projects around the world. Top: Their 1985 enrobing of Paris’s Pont Neuf. Photos © Wolfgang Volz

Just days after Christo and Jeanne-Claude sailed into New York Harbor from Paris in 1964, the artist duo hatched the idea of wrapping two prominent skyscrapers in fabric and rope. This is evident in a photocollage of Lower Manhattan with cloaked silhouettes of 2 Broadway and 20 Exchange Place, made during the artists’ initial stay at the Hotel Chelsea and reproduced in the new monograph Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Urban Projects. “I have a real need to appropriate reality,” Christo is quoted as saying in 1968. “By wrapping, I directly appropriate certain elements of reality.”

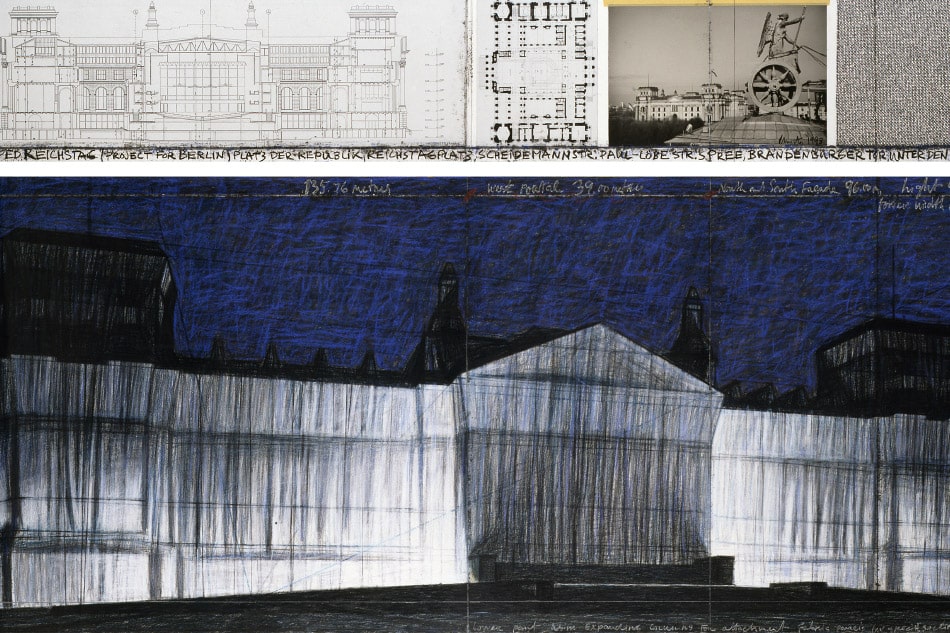

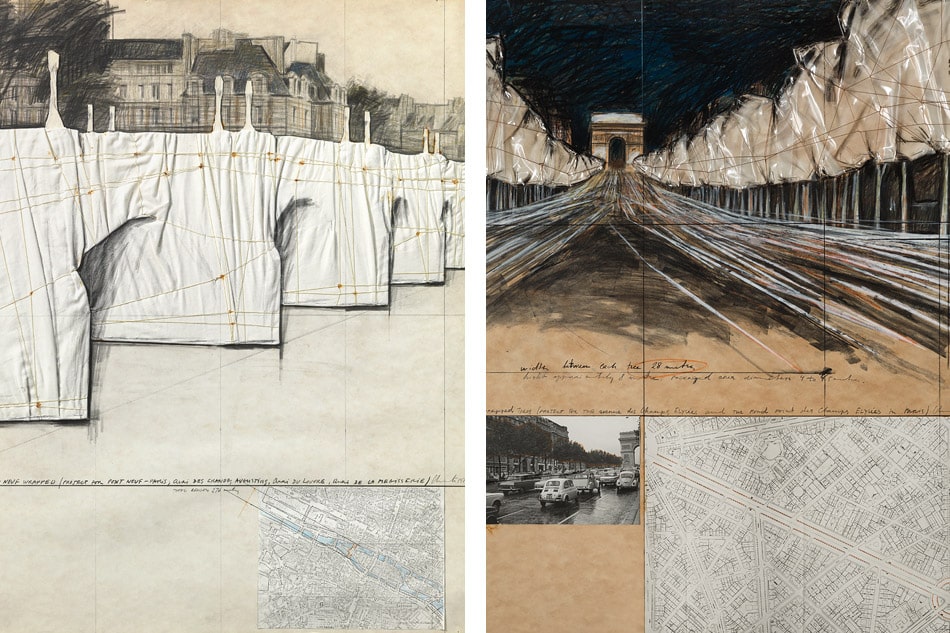

Christo and Jeanne-Claude would, of course, become world renowned for their obsession with wrapping significant urban structures — among them the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago in 1969; the Pont Neuf in Paris in 1985; and, perhaps most famously, the Reichstag in Berlin in 1995. That last one came to fruition after the artists spent 24 years seeking bureaucratic approvals and raising funds themselves through the sale of related drawings.

Urban Projects, published by Verlag Kettler and released in conjunction with a recently closed exhibition at the ING Art Center in Brussels, tracks the beginnings and development of their city-based interventions: about 30 projects proposed for buildings, streets, bridges and parks, only 13 of which were realized. The volume includes a sleeve with a separate booklet providing a complete illustrated timeline of all Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s urban and rural projects — 59 in total, 36 of which they failed to get permission for — making it a valuable reference on the scope of their work.

The idea to wrap Manhattan buildings in fabric and rope came to the artists almost as soon as they sailed into New York Harbor from Paris in 1964. Work © Christo

The book was written by the independent art historian Matthias Koddenberg, who in a phone interview recently described watching the 1995 wrapping of the Reichstag on television as an 11-year-old boy in a small town in Germany. Fascinated, he bought a book on the artists and wrote to them asking for an autograph. In return, a large package arrived stuffed with signed books and postcards. “That was the starting point,” he says. “I wrote again and again.” Their ensuing friendship over the years as Koddenberg pursued the study of art led to professional collaborations, one of which is the book.

Christo first landed in Paris in 1958 after fleeing communist Bulgaria the year before, where he had perfected his drawing skills during three years at the National Academy of Fine Arts in Sofia. A 1958 commission from the socialite Precilda de Guillebon to paint her daughter Jeanne-Claude precipitated the pair’s intense romance and lifelong artistic collaboration. (Jeanne-Claude died in 2009; the two considered themselves equal partners.) Part of a Parisian avant-garde scene that included Yves Klein and Jean Tinguely, Christo began appropriating everyday objects as art, wrapping empty bottles and cans in his studio. He then swathed oil barrels and even Jeanne-Claude’s shoes in cloth, turning them all into sculptures.

The couple also used oil drums as building blocks for sculptures, a lesser-known aspect of Christo’s practice that continues today. In 1961, shortly after the construction of the Berlin Wall, the artists tried unsuccessfully to get official permission to block one of the narrowest streets in Paris with a wall of 100 stacked barrels. The following year, they built the piece without authorization outside a gallery show. The pictures snapped before the police arrived were published widely and gained them art world notoriety.

“I have a real need to appropriate reality,” Christo said in 1968. “By wrapping, I directly appropriate certain elements of reality.”

The two New York City skyscrapers that Christo and Jeanne-Claude wanted to wrap were 2 Broadway and 20 Exchange Place. The project was never realized, but the pair continued to call the city home for decades, with Christo dubbing it, in 1965, “the most human city I have ever lived in.” Work © Christo

Although Christo had made a photomontage of a nonspecific building wrapped in fabric and rope before setting sail for New York, Jeanne-Claude later claimed in an interview that he was “just thinking.” It was the impact of the soaring skyline that inspired them to not just conceptualize but pursue working on a grand architectural scale for the first time, Koddenberg argues in the book. New York “is the most human city I have ever lived in,” Christo pronounced in 1965. “It is also the most cosmopolitan. . . . It is unstable, and that is good for creating.” At 82, he continues to live and work in the city.

New York may have been generative creatively, but the municipal powers proved resistant to the charms of the pair’s plan to fit 1 Times Square in Midtown Manhattan with a one-piece slipcover using 16,000 linear yards of fabric, at a cost in 1968 of $128,600 (about $900,000 today). “I understood that the only chance I would ever have to realize the wrapping of a building would be within the museum world,” Christo said retrospectively in 1991.

The couple’s first such success was swathing Switzerland’s Bern Kunsthalle for a week in 1968. But the initially enthusiastic director Harald Szeemann became less enamored of the project when he received an unexpected bill for 11,315.05 Swiss francs from the construction company handling installation and dismantling. The artists were forced to hand over original artworks to help defray the costs. This experience prompted them to take control of all funding for future projects from the outset, through the sale of Christo’s drawings illustrating each proposal.

Between 1972 and 1995, the couple produced some 600 original artworks visualizing the wrapped Reichstag — the then-former and, since 1999, current German parliament building — which is situated alongside the former Berlin Wall. Koddenberg writes that their proposal was an especially charged symbolic act of unification for Christo, given his personal relationship with the East-West conflict while growing up in Bulgaria.

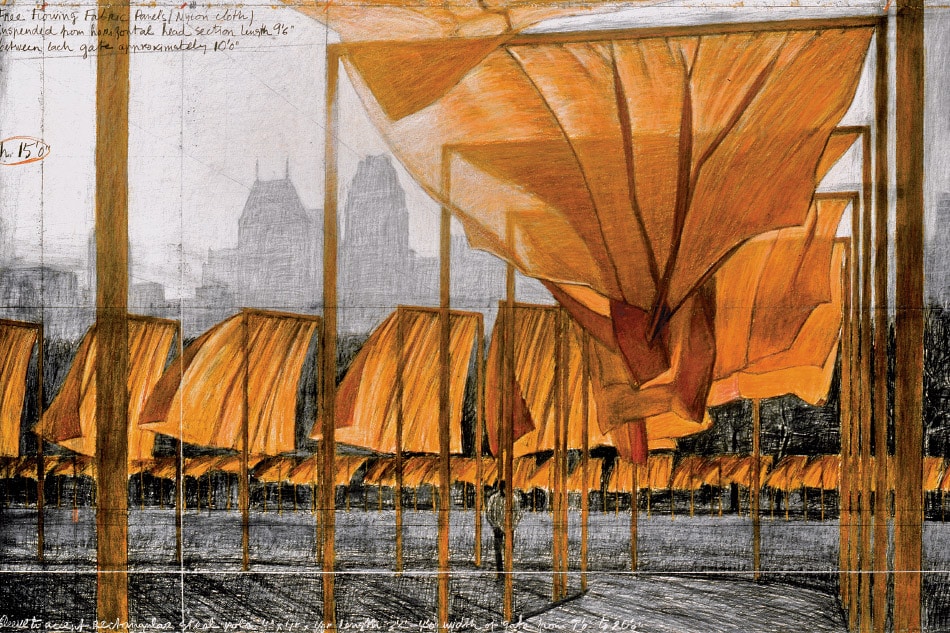

Urban Projects is infused with the art historian’s continued fascination with the generosity of Christo and Jean-Claude’s practice, including The Gates. The last of their realized urban works, that 2005 project invited New Yorkers to go for a glorious walk through 7,503 saffron-fabric-draped portals along the pathways of Central Park. More than 4 million people did.

“Christo enjoys very much the real things — the real wind, the real sun, the real rain,” Koddenberg says. “In all the projects, he tries to have people confront reality. If they want to see the project, they have to put on their jackets or their sun protectors and really be outside. They have to touch the things, go around them or through them or over them.”

Shop Christo and Jeanne-Claude on 1stdibs

Or Support Your Local Bookstore