In poetic prose, Umberto Pasti takes readers on a tour of his village retreat in Eden Revisited: A Garden in Northern Morocco (Rizzoli). Every piece of furniture in the kitchen of the property’s main house, which the author shares with his partner, Stephan Janson, was purchased, he notes, at local markets. Top: Photographer Ngoc Minh Ngo, Pasti writes, “claims that a photograph of this tree taken on her first trip to Rohuna is her self-portrait.” All photos by Ngoc Minh Ngo

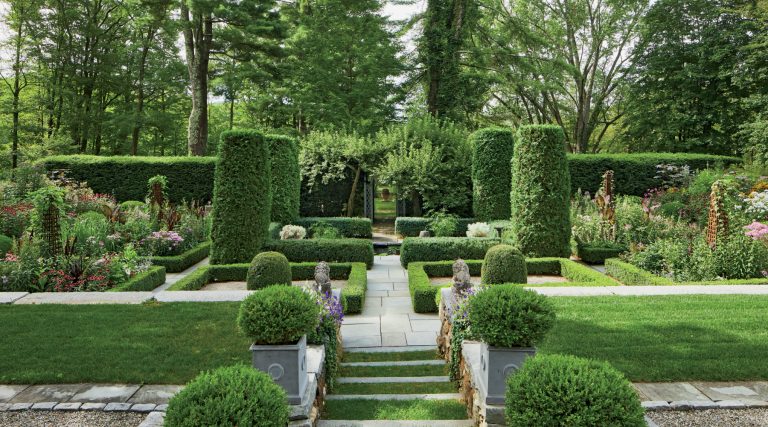

September 1, 2019Morocco has no shortage of great gardens. Some 700,000 visitors annually wend through the Jardins Majorelle, outside Marrakech, where Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé lived in a villa beginning in the 1980s. Countless others linger for hours at Jardin Jinan Sbil, in Fez, or les Jardins exotiques de Bouknadel, near Rabat. All are unquestionably beautiful. But no matter how lush or formal these places are, the role of man in shaping, taming and regimenting them cannot be escaped.

If you would rather immerse yourself in plantings that capture the mesmerizing, magical wildness of the North African soul and topography, you can do no better than to crack the binding of Eden Revisited: A Garden in Northern Morocco (Rizzoli), containing musings by Umberto Pasti and photos by Ngoc Minh Ngo. The book is a love letter to the property in Rohuna, a tiny village of 500 people on the coast between Tangier and Asilah, where the Milan-based Pasti and his partner, French-born fashion designer Stephan Janson, live when not in the Italian metropolis or their home in Tangier.

Ngo’s ravishing photography is clearly less concerned with documenting a landscape — although she accomplishes this admirably — than with taking the reader on a lyrical journey through mists, golden light, pools of cool shade and glaring sun so bright it blurs the contours of plants and flowers. Her eye is exquisitely attuned to surroundings and conditions that help illustrate not just what has been planted but how it feels to be in a place where numberless species thrive.

“Here is where I slept the first time I came to Rohuna,” Pasti writes of the exedra beneath the old fig tree. “Everything began here.”

But this is also a garden book written by an accomplished storyteller. Pasti has authored many novels, including The Age of Flowers, Più felice del mondo (Happiest in the World) and Perduto in paradiso (Lost in Paradise), the last inspired by the garden of his Rohuna retreat, which his poetic prose reveals to be his true spiritual home.

Pasti and Bernard, a Belgian gardener, shared a dream of having a tree dressed in bones. Together with Hamidou and Nabil and the other gardeners who tend the grounds, Pasti created what he calls “an open-air curiosity cabinet,” a surreal bone garden including an olive tree covered with animals’ skulls, ribs and the like.

“I arrived twenty years ago with a friend who lived here and who wanted to show me a place where no nazrani, no foreigner, had ever set foot before,” Pasti writes in his introduction. The villagers eyed him skeptically.

“We came down,” he continues. “There was a fig tree. I sat down in its shade and fell asleep. I dreamt that this place was my body and my body was a garden.”

“The young schotia and cassia trees, the euphorbias and the aloes disappear under the red horde of the poppies,” Pasti writes of an area he calls the Garden of the Portuguese.

The Garden of the Portuguese features a bench covered in 16th-century Sevillian tiles and fragments of Fez tiles from the same period.

“There was turf where my hair had been. I had turned into a garden that had already been there once, who knows when. Around us there were dry thistles that looked like voodoo pins torturing the earth, tufts of dwarf palms, stones, a few wild olive trees, a few mastic trees with leaves reddened from thirst, and sand dunes down below.”

From here, Pasti weaves a rich tapestry of myth and remembrance. He creates imaginary characters and fictional histories for the individual gardens, terraces and plants found in this eden. As the creator of the Garden of the Portuguese, for instance, Pasti dreams up a melancholic 18th-century Portuguese botanist with threadbare silken breeches, a torn yellowed jabot and sagging tricorne hat. “His pale hand caresses the tiles. Half-closing his eyes, he sighs. Just like me, he has many interests and two whims: flower bulbs and old tiles.” The Garden of the Italian is an autobiographical assembly of plantings “with the same mood and the same perfume of my childhood siestas, outdoor games, merende . . . “

“I planted these olive trees where they were twenty inches high,” Pasti writes. “Today I read while sitting in their shade.”

Other gardens carry the names of the (real) men who tend them: Lotfi, Nabil, Chinioui, Hamidou. Like any good novelist with a deep affection for his characters, Pasti brings each vividly to life. Chinioui (to whom Pasti administered antibiotic injections to battle pneumonia when the gardener was a boy of six) sees to terraces planted with fruit trees — figs, apricots, mulberries, pomegranates, quinces and pears — under which grow agapanthus, Canary Island daisies that “look like clouds of cherubs crowded around the Madonna,” clivia, lantana, herbaceous perennials and succulents. On another terrace, Hamidou and Nabil helped Pasti conjure a surreal bone garden. To create this “open-air curiosity cabinet,” they layered the trunk of a wild olive tree with the skulls and bones of cats, dogs, rabbits, goats, donkeys and other animals that had died in the surrounding fields and draped branches with “tinkling ladders of ribs and weighty pendants of tibias.”

For Pasti this image recalls “an August evening under the apricot tree.”

Then there’s Bernard. A “Belgian gardener who knows and loves plants as only someone who is hiding an inner scar can,” he took up residence in Rohuna four years ago and works with Pasti on his grounds. Throughout the book, Pasti delivers an immense amount of information: about the indigenous flora of Morocco, about rescuing wild species from the front-end loaders and bulldozers wielded in development’s inexorable march forward, about the perils of challenging Moroccan rural property laws. What began as a 2-acre purchase has now grown to 25.

Pasti’s description of another of the gardens, the Gharsa Baqqali, encapsulates the mystical quality suffusing the property as a whole, humming through it like the millions of creatures that crawl and slither under the earth: “The very idea of a garden upsets me; I shake it off, like a mule does with horseflies. This is a place, and a place is much more than a garden. This is where you lie down to eat, sleep, study, think, pray, and make love.

“If for a single moment,” he continues, “I were to become aesthetic and to conceive, God forbid, an image of nature subdued and refined, . . . then I would deserve to lose this wide piece of land. The jennan, the genies of this place, would become furious and hand it over to my adversaries.”