March 3, 2019An icon in the world of postmodern furniture, Italian designer Alessandro Mendini died last month at the age of 87. He’s seen here in his Milan studio, the setting of all the photographs in this remembrance, which were captured in the summer of 2017 by photographer Manfredi Gioacchini as part of a series of portraits of architects.

Everything he did was poetic,” says Christian Larsen, a curator of modern decorative arts and design at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, describing Alessandro Mendini, who died last month at 87. Mendini created some of the most recognizable objects of the past half-century (more than 2 million of the designer’s Anna G. corkscrews, its feminine profile inspired by his friend Anna Gili, have reportedly been sold by Alessi). But in his 60-year career, he was as much a writer, teacher and philosopher as a designer.

“He was tremendously serious as a person, as a theorist, even if he used all those colors,” says Alessandro Padoan, owner of Milan’s Fragile gallery. Mendini designed the space in 2013 as an antidote to white boxes, with pistachio green walls and floors that mix yellow and bubble-gum pink. Padoan spoke by phone with Introspective just after attending Mendini’s funeral, held, as a sign of his significance, at La Triennale di Milano.

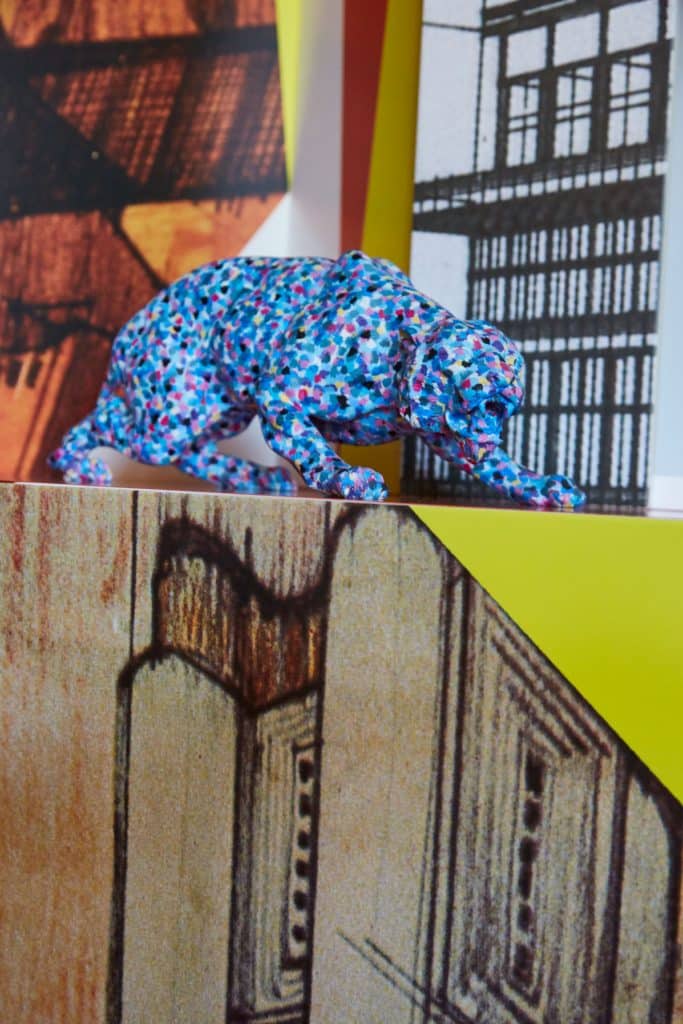

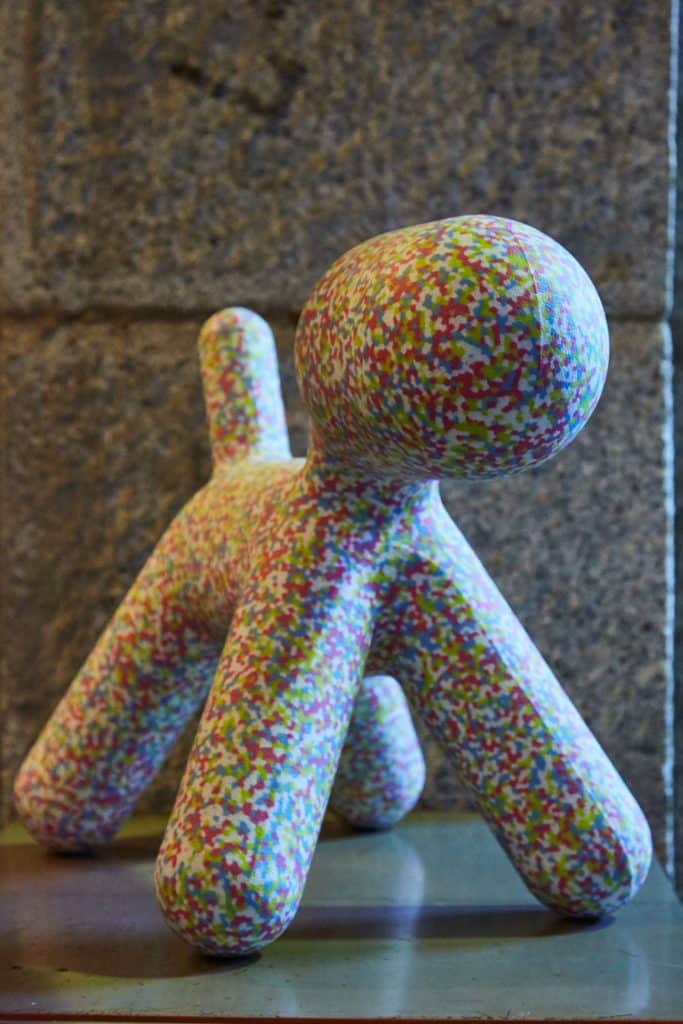

In a 2015 interview, Mendini described his most famous piece of furniture — the ornate wooden Proust chair, covered entirely in a motley, confetti-like pattern — as “an intellectual exercise,” explaining, “It has no function. It’s only for amusement.” Even so, the item became so well known that galleries today do a steady business selling even his ceramic miniatures of it.

Keith Rennie Johnson, who runs the Brooklyn gallery Urban Architecture and knew the designer well, has sold about 20 full-size Proust chairs over the years. Every time he gets one, he says, “it is scooped up immediately by an important collector.” On 1stdibs, Johnson is currently offering Mendini’s rare Cetonia commode from 1984, created for the Italian manufacturer Zanotta and covered in designs reminiscent of the constructivist work of Wassily Kandinsky.

“His whole theory was that we don’t need to keep inventing new objects when there are so many ideas that can be explored on objects that already exist,” says Johnson, explaining that, with his surface treatments, Mendini “would create something completely new without conjuring up an entirely new form.” Johnson says that the designer’s onetime protégé, the Memphis founder Ettore Sottsass, “was always in search of new forms” and recalls hearing Mendini — whom he characterizes as “a very courtly man, and smart, smart, smart” — chastise Sottsass: ‘There’s too much already, Ettore.’ ”

In the studio, a painting by Mimmo Paladino featuring a portrait of Mendini sits atop an antique commode.

Larsen says Mendini was the “more radical” of the two: “If Sottsass was the sun, Mendini was the moon, and he was as mercurial as the moon.” Johnson points out that, without Mendini, who promoted radical ideas as editor of the magazines Casabella (in the 1970s) and Domus (in the 1980s), “there never would have been a Memphis or the opportunities it afforded Sottsass.”

“Mendini exercised great power with his words,” agrees Evan Snyderman, coprincipal of the New York gallery R & Company and author of the introduction to the 2017 book SuperDesign: Italian Radical Design 1965–75 (The Monacelli Press). As a writer and editor, Snyderman notes, Mendini helped determine the direction of Italian and global design for decades.

Born in 1931 to a prosperous Milanese family, Mendini attended the Politecnico di Milano during a time of intellectual upheaval. After graduating in 1959, he went to work for the designer Marcello Nizzoli, who helped revitalize postwar Italian industry with products for Olivetti and Necchi (manufacturers of his typewriters and sewing machines, respectively). But Mendini was intent on critiquing, not contributing to, postwar consumerism. In 1975, for instance, he designed the Lassu chair, which sat high atop a stepped platform. That already made it unusable, but the designer went on to burn it to ashes in a “performance” he photographed for the cover of Casabella. During this period, he was as much provocateur as designer. “The chair that doesn’t exist is his most important design, because of all of the contradictions embedded in it,” Larsen says. (Smaller versions of Lassu remain.)

A riot of artworks, models, mock-ups, prototypes and assorted other works in progress — including a series of skateboards for the company Supreme — fill the Mendini studio, which is located on Milan’s Via Sannio, not far from the Fondazione Prada.

Both Sottsass and Mendini fought against what they saw as the soullessness of modernist design, but not always in the same way. In 1976, Mendini cofounded Studio Alchimia, which Larsen describes as “a collaborative effort among like-minded designers to take all the excess stuff circulating around the globe, reuse it, recycle it, adapt it and create anew.” Sottsass was briefly a member of Alchimia but, unlike Mendini, chose to pursue mass production.

A small version of Mendini’s Unicorno stool sits amid assorted vessels.

“At that stage of his life, Mendini was an antiestablishment, anticommercial designer,” says Snyderman. But along with Sottsass, he went on to be a force in postmodernism, which Padoan calls the world’s “last important design movement.”

So, Mendini, the deep thinker, became known for riotous colors and patterns, which he applied to everything from Swatch watches to lighting. The Deriva di Proust ceiling fixtures he created for Padoan’s gallery, for instance, are decorated in designs that recall the chair whose name they share.

“Much like Sottsass, Mendini was interested in the surface of the object as the site of aesthetic appeal,” says Larsen. The designer’s approach, he adds, “succinctly summarizes the basis of postmodernism, which is about variation, diversity, fragmentation, multiplication, surface decoration — the superficial, as opposed to some kind of core universal identity, which is what modernism is about.”

Learn more about Alessandro Mendini