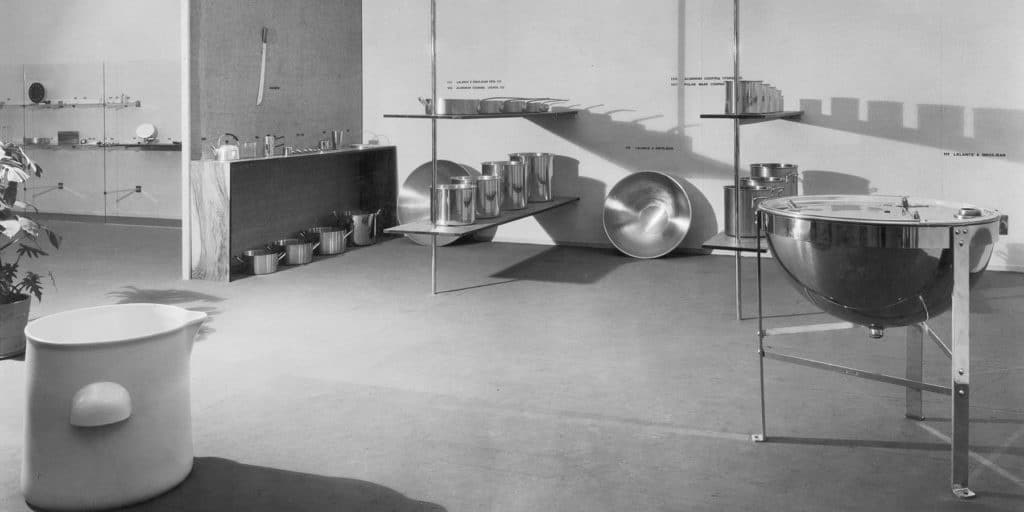

September 4, 2017On view at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery through December 9, “Partners in Design: Alfred H. Barr Jr. and Philip Johnson” explores the impact of the friendship between the two MoMA alumni on modernist design in America. Top: An installation shot from 1934 of one the duo’s seminal shows, “Machine Art.” Both photos © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York

Philip Johnson is most fondly remembered today as the wise old owl of modern architecture, which makes it easy to forget that he was once a precocious young man. In fact, he was only 23 years old and had never formally studied architecture when New York’s Museum of Modern Art opened its doors in 1930 and he began organizing its landmark “Modern Architecture” exhibition of 1932. He had been recruited by Alfred H. Barr Jr., the 27-year-old director of the fledgling institution, at a moment when both men were smitten with ideas emerging from the Bauhaus.

Johnson and Barr had become fast friends in 1929 after meeting at Johnson’s sister’s graduation from Wellesley College. In the years that followed, they toured Europe together to study the new architectural landscape and lived a floor apart at the Southgate apartment building in Manhattan’s Midtown East, where they used their homes as incubators and showcases for modernist ideas and furniture. The groundbreaking exhibitions they organized helped shape both the development of modern architecture and design in America and the role of contemporary museums around the world.

This powerful friendship is the focus of “Partners in Design: Alfred H. Barr Jr. and Philip Johnson,” a traveling exhibition on view at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery from September 7 through December 9, with a supporting catalogue published by The Monacelli Press. The show was organized by David A. Hanks (curator of the Liliane and David M. Stewart Program for Modern Design, which is housed within the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts), in collaboration with that museum, where the show originated. Introspective caught up with Hanks to learn about the surprising discoveries he made during his research.

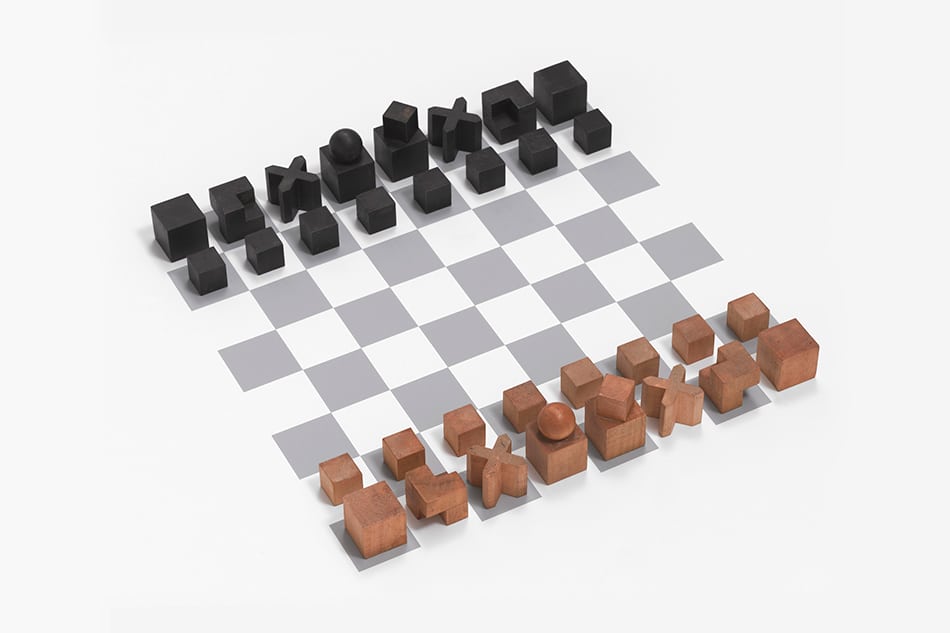

The 1934 exhibition “Machine Art,” organized by Alfred H. Barr and Philip Johnson, elevated industrial design to the level of art for the first time. © Estate of Josef Albers/SODRAC (2015)

1. Why did you organize this exhibition?

At the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, we were given an important gift from Victoria Barr of the original furnishings from the Alfred and Marga Barr apartment of 1930 [her parents’ former home], which was one of the earliest modern apartments in New York. We didn’t know who had designed the furniture. We checked MoMA correspondence and couldn’t find anything about it.

As we pursued the research, we found out that their apartment was directly above one moved into earlier by Philip Johnson, who had commissioned Ludwig Mies van der Rohe to design it and its furnishings. Barr and Johnson were really very close friends, and the apartments became their offices, where they worked and collaborated. They were experimenting with their apartments at the same time they were doing the “Modern Architecture” exhibition at MoMA. These homes were laboratories.

2. You eventually figured out that the Barrs’ furniture was designed by Donald Deskey. Was that a surprise?

Yes, because MoMA didn’t like industrial designers who were known for Art Deco or streamlined design. But the Deskey furniture they chose was tubular steel, which was basically inspired by Marcel Breuer and other Bauhaus designers. The apartments were very different. The Johnson apartment was all furniture designed by Mies and [his collaborator] Lilly Reich, and it was very costly, as it had to be made to order in Germany and shipped over.

The Barrs couldn’t afford this kind of apartment, so they did what they could with American design, which was less expensive and more available. They did it with very little money but a great deal of taste and intelligence. Johnson’s was almost a fluke. He said he had visited Mies and said: “Oh, I’m getting an apartment in New York, and I’ll have you design it.”

3. How did Johnson end up in such an influential position at MoMA despite having not yet studied architecture?

There probably weren’t many jobs, if any, for a curator of architecture, anywhere. It was a new field. Johnson began to learn, and Barr was really his teacher. Barr gave him a list of places and architects to see in Europe. Johnson knew nothing about paintings either, but he learned from Barr. He later became an important art collector, knowledgeable in his own right. But that initially wasn’t his field — he was a philosophy major. His youth and enthusiasm are part of what made him such a success.

Marcel Breuer B32 chair, 1928. Photo courtesy Sotheby’s, New York

4. Johnson left MoMA in 1934 to indulge his interest in politics and earned his bachelor’s in architecture in 1943 before returning to the museum in 1946. What happened to their friendship during this period?

There was this parting of ways when Johnson became infatuated with fascism and Nazis. But Barr didn’t desert him. He criticized him and was very unhappy with what was happening but continued to be his friend. He was extended family. You know, even when a son does bad — or wrong — things, you don’t desert him completely.

5. What influence did their partnership have on the development of modern design in America?

The “Modern Architecture” show had an enormous influence, whether critics liked it or not. Their championing of the Bauhaus was important. The “Machine Art” exhibition in 1934 was a complete surprise to everyone who saw it. Until then, people had no idea that industrial design could be looked at as art. At the same time, MoMA was developing departments of film and photography. It was pretty much first in advocating and developing departments in these broader areas of the arts to reflect culture as a whole, not just the fine arts. These things that we take for granted today were then really new ideas.