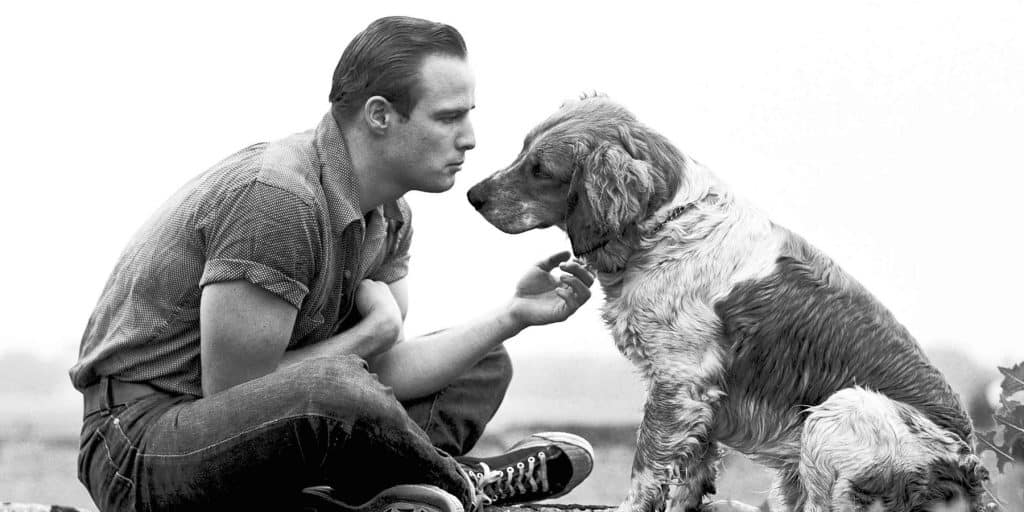

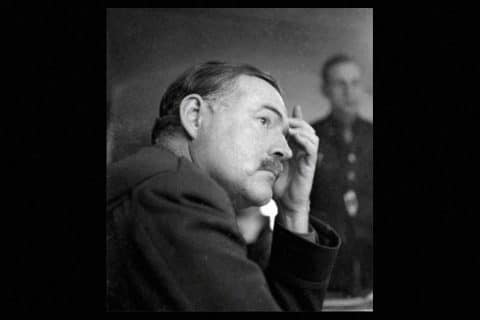

December 18, 2017Photographer Art Shay’s legendary career was launched when images he shot as a navigator for the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War II were published in a national magazine. Shay took this self-portrait in 1966. Top: Marlon Brando, 1950, offered by Morrison Hotel Gallery. All photos by Art Shay, unless otherwise noted

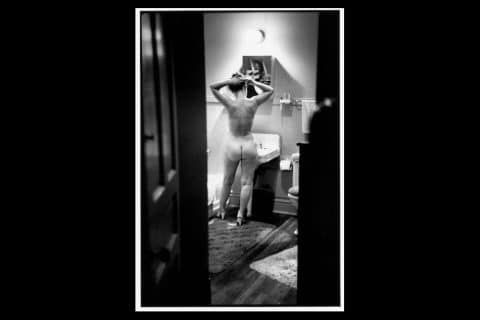

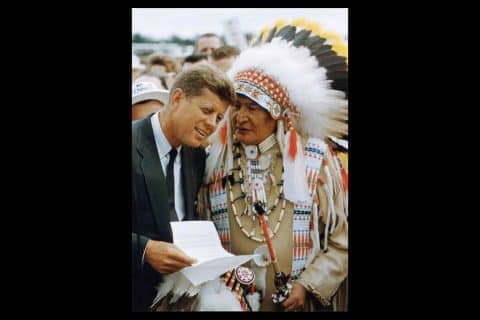

At 95, Art Shay has photographed everyone from Ernest Hemingway and John F. Kennedy (and seven other U.S. presidents) to assorted mobsters and a nude Simone de Beauvoir. But when asked to choose a favorite picture, he bypasses his photojournalistic triumphs (Khrushchev in an Iowa cornfield, the tear-gas-cloaked 1968 Democratic National Convention) and celebrity portraits (Elizabeth Taylor by candlelight, a budding actor named Marlon Brando) in favor of anonymity and ambiguity, such as a scene he captured one winter night in the late 1950s through the illuminated window of a Chicago beauty shop. Sharply visible beyond the soft-focus phalanx of elaborately bewigged mannequin heads is a lone, less-than-glamorous customer seated beneath a helmet-like hairdryer.

“The mannequins are what we want to look like,” says Shay. “The lady is who we are.”

Some 50 years later, he still recalls the setting on his trusty Leica (f/2 at 1/30) at that decisive moment and at many, many more in a career he characterizes as “casually monitoring the space between illusion and reality.” The Lucie Foundation recently recognized his “monitoring” with its 2017 Lifetime Achievement award, bestowed in New York’s Carnegie Hall. To receive it, Shay traveled to Manhattan from Deerfield, Illinois, where he has lived since 1958, raising five children with his late wife, Florence. He was accompanied by his assistant and archivist, Erica DeGlopper, and a film crew gathering footage for an upcoming documentary (working title: The Art of Art Shay).

Even the capstone achievement represented by the award can’t overcome his inherent modesty. “At my age, you take whatever acclaim comes to you, and you’re proud of that,” the photographer says. “Then, you wonder how everybody found out about you.”

Elizabeth Taylor, 1960, offered by Morrison Hotel Gallery

It helps to have had an early start. Bronx-born Shay shot his first pictures at the age of 12 on his father’s folding Kodak. He learned developing and printing as a Boy Scout and, after investing the proceeds from neighborhood gigs photographing babies and bar mitzvahs, traded up to a $10 Graflex. A navigator for the U.S. Army Air Force during World War II (the actor Jimmy Stewart was his commanding officer), he trained his secondhand Leica during one combat mission over Germany on a midair collision between two B-24 Liberators. The photographs got a page to themselves in a September 1944 issue of Look magazine, becoming Shay’s first published pictures.

After the war, as a reporter — and then bureau chief — at Life, Shay worked closely with many of the magazine’s legendary photographers and distinguished himself as what he calls “an idea man” with a knack for saving the day on go-to-press nights. Life photographer Francis Miller dubbed Shay “DeMille” (after filmmaker Cecil B.) for his ability to find — or whip up — drama in even the most mundane circumstances, as when, for Shay’s first big Washington, D.C., story, he hired a college junior to crash a party at the Hungarian embassy. A highlight of the evening was a shot of the furious Hungarian ambassador, one Rusztem Vámbéry, brandishing a salami.

“I could do all kinds of things with the camera that most other reporters couldn’t do,” says Shay, who often brought along a camera on reporting assignments as a neophyte writer and tasted the “bittersweet anonymous glory” of having his pictures published under the name of the photographer he was working with. “I breached one of the no-no’s of Life magazine — you didn’t change disciplines mid-story — and when it came out, I got in big trouble.” And so, a freelance photojournalist was born.

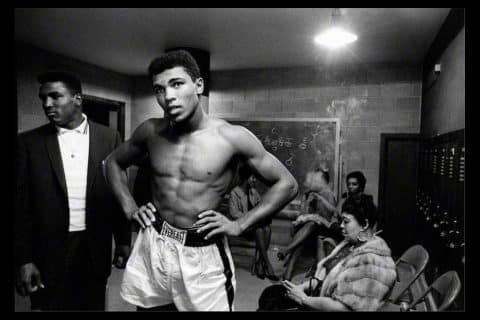

Based in Chicago starting in 1948, Shay quickly became a go-to lensman for such publications as Life, Time, Fortune, Sports Illustrated and the Saturday Evening Post, amassing an archive (estimated by DeGlopper to comprise approximately two million images) that brings together the banal and the beautiful, chance and skill, icons and outlaws.

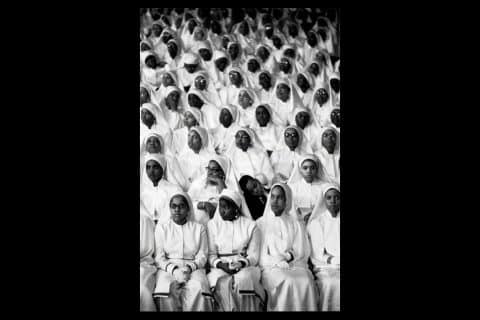

“He didn’t discriminate or categorize himself if he saw a story to tell,” says DeGlopper, a graduate of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, who has worked with Shay since 2005. Vast in its scope, his oeuvre spans the second half of the 20th-century in America. “Civil rights, sports, politics — it seems like he was everywhere at once,” says Victor Armendariz, whose Chicago gallery will mount an exhibition of Shay’s work in May 2018.

“What sets Art Shay apart is his life experiences,” says Peter Blachley, owner of Morrison Hotel Gallery, which represents Shay in New York and Los Angeles. “The great photographers all had formative years of doing work for magazines. It was very competitive and pushed them to do their best work, which is revealed in their subjects and technical expertise.”

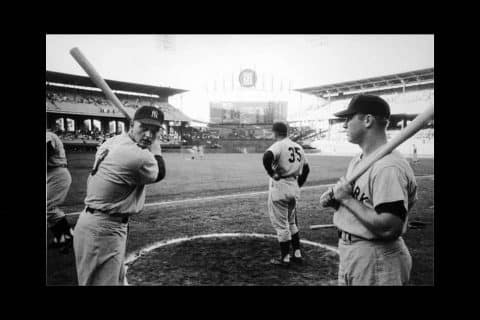

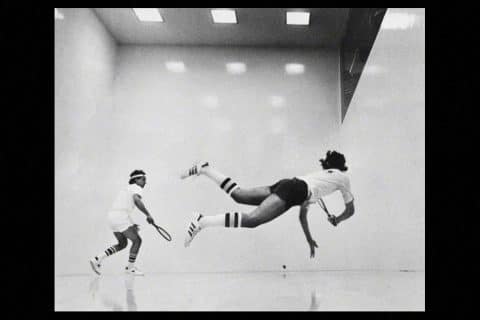

With a sharp eye for incongruity — often delightful, sometimes tragic, occasionally both — Shay is a master of juxtaposition, both found and made. Many of his most memorable images are animated by opposing forces: the disparate tilts of Maris’s and Mantle’s bats framing the on-deck circle at Comiskey Park, a small child aiming his toy pistol at gangster-busting Senator Estes Kefauver, bayonet-wielding militiamen assembling beneath a glowing marquee proclaiming “Welcome Democrats.” Compositions such as these are an invitation to compare and contrast, and Shay prefers to leave it at that. “If you have to explain it, you shut viewers out of the joy of discovering things for themselves,” he says.

The American Writers Museum, in Chicago, currently has a special exhibition devoted to Shay’s portraits of such literary luminaries as Allen Ginsberg, James Baldwin, Gwendolyn Brooks and his longtime friend Nelson Algren. The show opens with a shot of baseball-player-turned-writer Jim Brosnan, whom Shay photographed sitting at his typewriter on the pitcher’s mound at Wrigley Field, in the snow. “It’s witty — and exactly right,” says historian and author Tom Dyja, who organized the exhibition. “He was very influenced by the French artist [Honoré] Daumier, so he has a sense of the human comedy, but also of people as characters and individuals more than just types.”

“At my age, you take whatever acclaim comes to you, and you’re proud of that. Then, you wonder how everybody found out about you.”

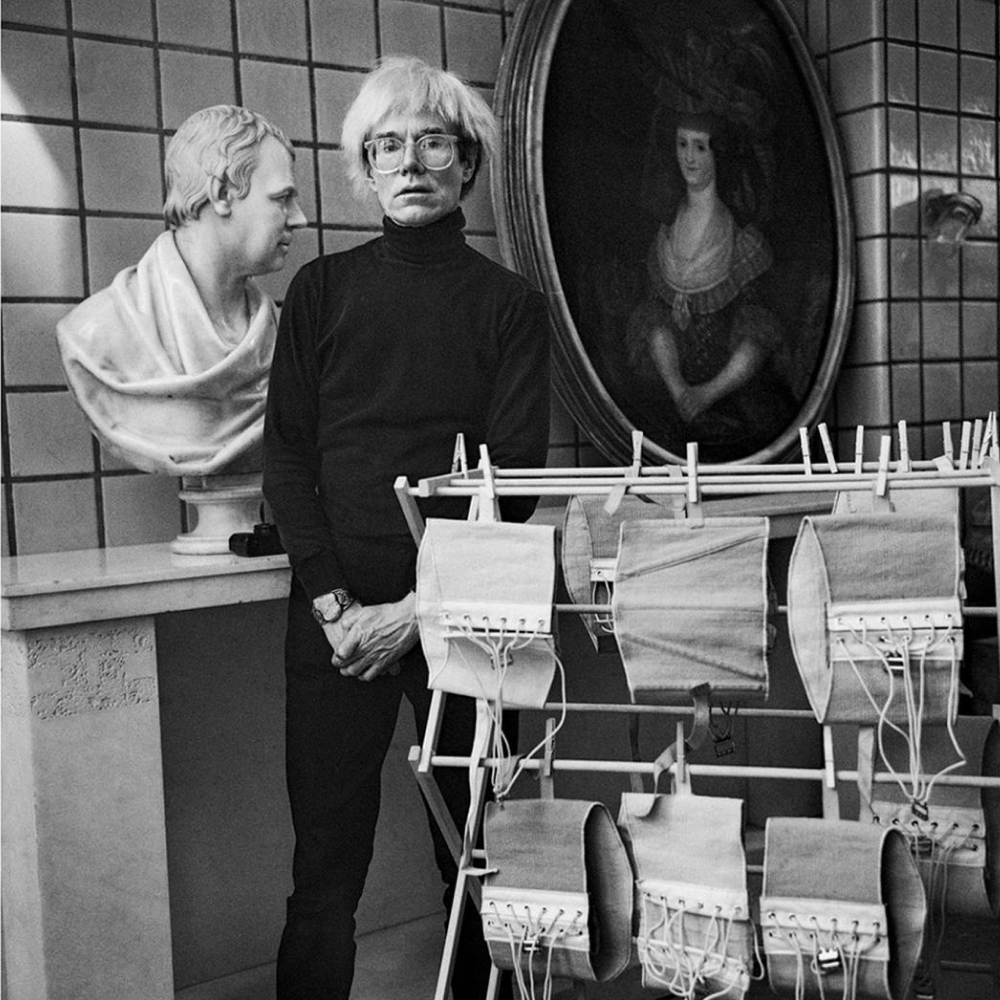

Shay, now 95, was honored by the Lucie Foundation with its 2017 Lifetime Achievement award (portrait by Sandro Miller).

Shay’s portraits, whether of smiling street urchins or grimacing Mafia dons, Judy Garland or Jimmy Hoffa, are united by their intimacy — less a visual trait than a photographic feat made possible by spirit (humane), distance (two steps closer than everyone else) and timing (impeccable). “When I look at his pictures, I feel as if I’m allowed to live in the moment with the subject,” says Armendariz.

With an estimated 30,000 published pictures to his credit and 100,000 digitized for easy access, there is still much for curators and editors to explore. The photographs Shay took after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, for instance, will feature prominently in the commemorations next year of the 50th anniversary of King’s death, including an exhibit planned for the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis.

Meanwhile, Shay, DeGlopper and historian Erik Gellman are working on a book titled Troublemakers: Chicago Freedom Struggles through the Lens of Art Shay, due out in early 2019 from the University of Chicago Press. And Sports Illustrated recently sent Shay more than 2,000 rolls (“about a hundred pounds of negatives,” he says) of his freelance work.

With only a few regrets, including turning down Cornell Capa’s 1952 entreaty to join the Magnum Photos agency, Shay is left today with a limitless supply of good stories, most of which end with four words: “I got the picture.”

And that original Leica? He smiles at the thought of it. “I could still load it in my sleep!”