November 15, 2020Discovering surprising artistic crosscurrents and unexpected connections among works of art is part of the enjoyment of museum-going. Just walking in the door of an art-filled building can be a revitalizing pleasure.

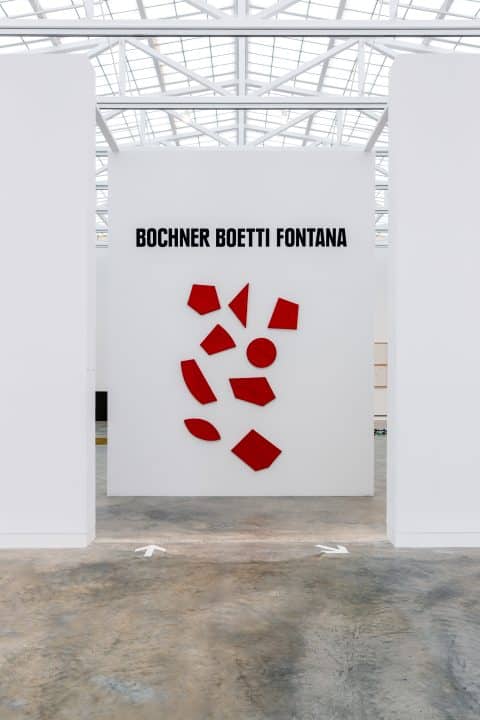

One of those edifying exhibitions that made us see art and visual culture afresh was “Bochner Boetti Fontana” at Magazzino Italian Art, a museum housed in a sleekly contemporary concrete-and-glass building, designed by Spanish architect Miguel Quismondo, just 60 miles up the Hudson River from Manhattan, in Cold Spring, New York.

The exhibition featured three legendary artists: one American and two Italian. The juxtaposition illuminated the parallels between several art movements of the 1960s and 1970s — Spatialism and Arte Povera in Italy and Process and Conceptual art in the United States.

Magazzino was an especially apt home for this show. The institution was founded by husband and wife Giorgio Spanu, an Italian, and Nancy Olnick, an American, to showcase the couple’s trove of Arte Povera–focused Italian art. Olnick and Spanu had met Mel Bochner at a gallery dinner, and they quickly hit it off. Soon, they began hatching a plan for the Magazzino show.

Mel Bochner’s Italian-American Concept

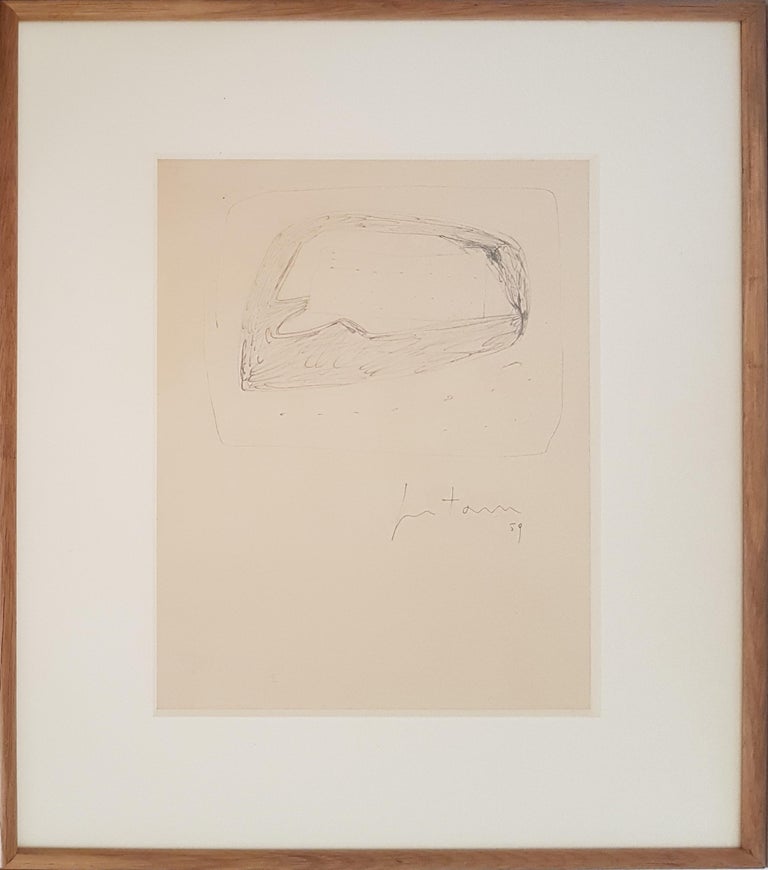

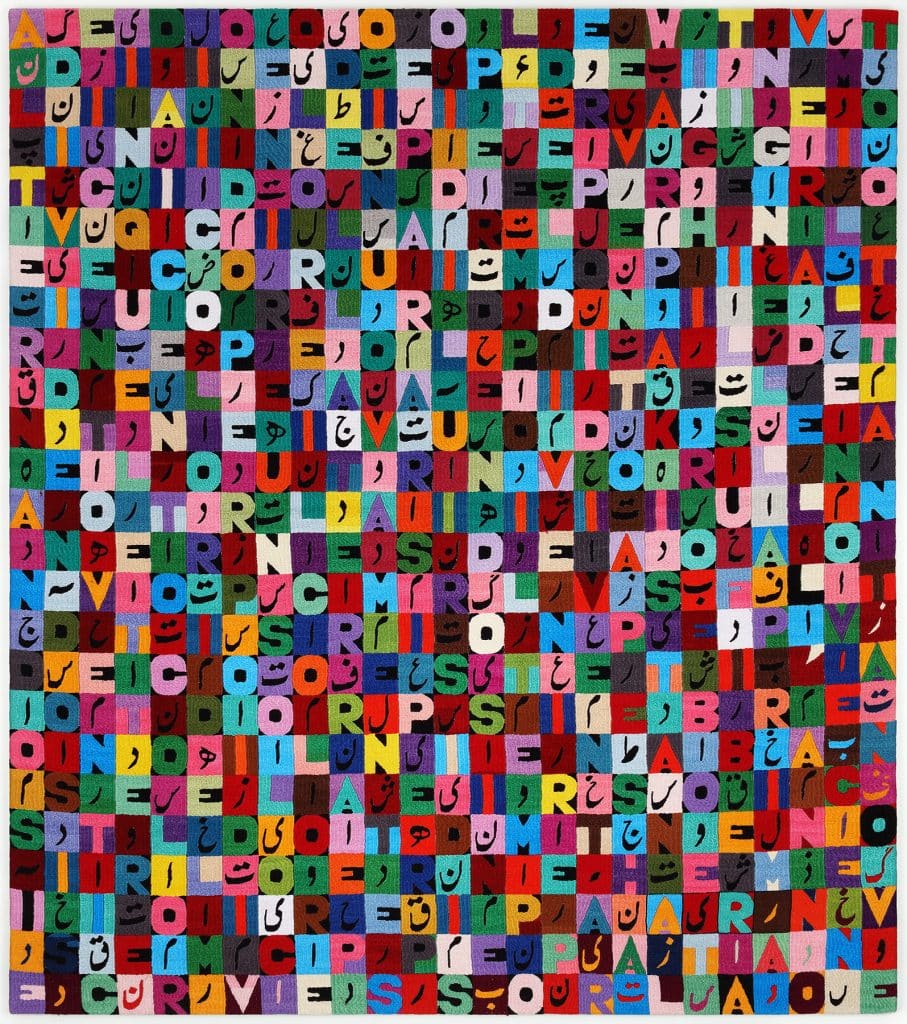

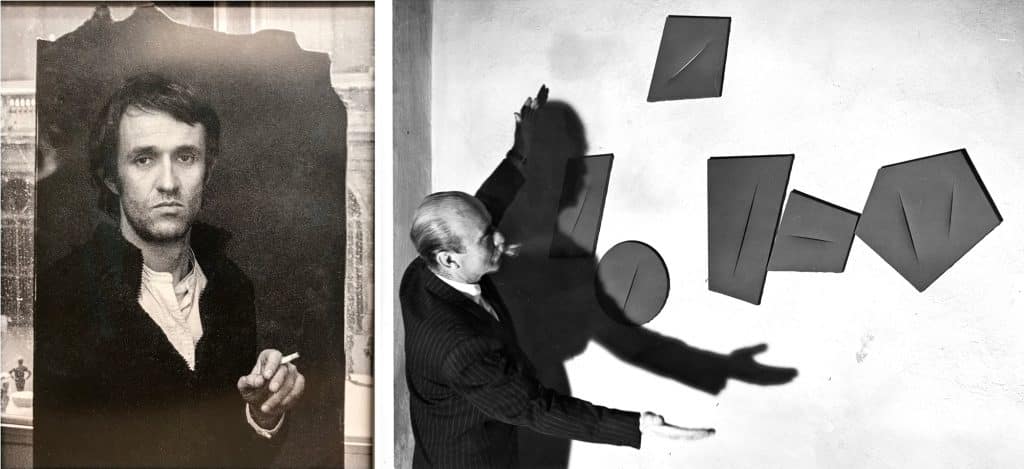

“Bochner Boetti Fontana” was small and powerful, comprising 17 works. Bochner presented seven of his own paintings and sculptures. They joined five grid-based pieces by post-war Italian art star Alighiero Boetti (1940–94), a key figure of Arte Povera, the 1960s and ’70s movement of “plain” or “poor” art that is essentially an Italian branch of conceptualism. Also on view were five works by Lucio Fontana (1899–1968), a founder of Spatialism, who was later famed for his slashed-canvas paintings, which exemplify his ability to grab the viewer with bold visual gestures.

The Boettis came from Spanu and Olnick’s collection, while the Fontanas were on loan from the Fondazione Lucio Fontana and private collectors. Bochner supplied his own works.

The show “is not about compare and contrast, which I despise,” says Bochner, who is perhaps most famous for his witty text-painting series that plays with the phrase “Blah Blah Blah.” Instead, he continues, “it’s about hopefully taking a viewer on some kind of journey and seeing works that speak to each other.” As you might expect from a conceptual artist who paints with words, he doesn’t mince them.

The opening work was Fontana’s 1960 Concetto Spaziale, Quanta, composed of an array of painting fragments whose deep red color echoes Bochner’s Measurement: 12 Inches Between, a red rectangle with a small square cut out of its center and a white square the size of the missing piece placed to its side.

The blue grid of Bochner’s Counting: 24 Trajectories (1997) plays off the orange of Fontana’s classic 1959 slash painting Concetto Spaziale, Attese (Space Concept, Waits), displayed next to it.

Themes Explored in “Bochner Boetti Fontana”

Arte Povera — which often used humble materials to offer a thoughtful look at immigration and nationality, as well as a critique of postwar Italian society — wasn’t exactly known as a laugh-a-minute movement. But Bochner’s take on Boetti reveals the levels of sophistication that imbue the works of the three artists in the show, all of whom deftly surf the line between humor and seriousness.

“They share a sense of irony,” says Olnick.

Measurement — with the deeper meaning of how we assess the world around us — is a theme that crops up again and again in the art on view. It’s also a concept that was vividly present to visitors of the show, as Magazzino used the technology to enforce social distancing in the age of Covid-19: Museum-goers wore lanyards attached to buzzers that vibrated if they came within six feet of anyone else’s.

The use and meaning of text are also explored in the works on display. Among these is the Fontana work Io Sono un Santo (1958), thought to be his first punctured canvas, which contains the title phrase, meaning “I am a saint,” in graphic script on a neutral background, with a less legible “non” (“not”), inserted after “Io.” Not far away, Boetti’s Tavola pitagorica (1990), with its grid of letters, evokes the stacked words of Bochner’s Blah, Blah, Blah (2009).

Mel Bochner’s Past Shows and Collaborations

Bochner says he hasn’t curated a show since 1966, when he put together the pioneering “Working Drawings and Other Visible Things on Paper Not Necessarily Meant to be Viewed as Art” at the School of Visual Arts in New York.

“It was an exhibition of books of xeroxed copies of other artists’ works,” he says. “And it’s sometimes considered the first work of conceptual art.” The project featured the work of such artists as Sol LeWitt, Edgar Orlaineta, Allen Ruppersberg, Adrian Piper, and Marcel Broodthaers.

The Magazzino show did have a more recent antecedent, however. A few years ago, Bochner collaborated with gallerist David Totah, who has a space on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, on an exhibition of his works and Boetti’s.

“It had Boetti’s embroideries, which have text and color, and my paintings on velvet, which have text and color,” says Bochner. “David thought that was a really interesting juxtaposition, and it turns out to be so.”

Bochner’s History with Fontana and Boetti

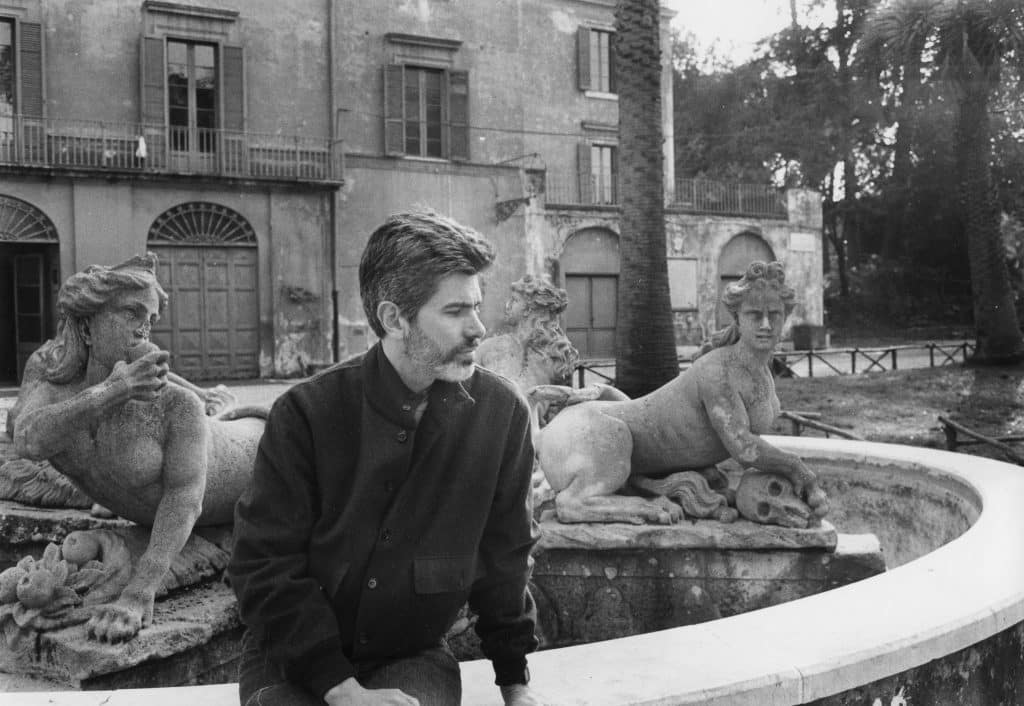

The roots of Bochner’s interest in the two late, great Italian artists goes way back, to when Bochner was a student at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, in Pittsburgh, and saw Fontana’s radical work at the 1961 Carnegie International exhibition.

“At the time, nothing surprised me — not Willem de Kooning, not Franz Kline, not Robert Motherwell,” says Bochner, citing some of the cutting-edge Abstract Expressionist painters of the day. “But in the last room, there was a large canvas, slashed down the center, and I was just shocked. And I went up to the guard and said, ‘Listen, somebody just slashed that painting in there.’ He laughed and said, ‘Everybody thinks that, but the artist slashed it himself.’ And I went, ‘Really? Why would he do that?’ That was my first Fontana experience.”

Bochner met Boetti in 1970, when they were shown together in Turin, Italy. “While we were very different, there were some conceptual relationships in terms of systems, series, repetition and common materials,” Bochner says of the dialogue between his work and Boetti’s. “He and I were on a similar wavelength. And also I appreciated what I took to be his humor. He was a funny guy.”

The Playful Side of Mel Bochner

The playful and inventive side of Bochner that comes out in Blah Blah Blah is also evident in his floor sculpture Meditation on the Theorem of Pythagoras (1972/1993), comprising rows of small, smooth chunks of Murano glass in a rainbow of colors, a nod to Italy and its influence. (Olnick and Spanu happen to collect Murano glass, too.)

Through its complex mixing of European and American sensibilities, the show “goes beyond any sort of provincial sense of national origin,” says Bochner. It’s a cosmopolitanism that suits Magazzino — a museum of Italian art in the Hudson Valley, founded by an American (Olnick) and an Italian (Spanu) — perfectly.

It’s easy to engage with these works even as they retain their conceptual mystery — they draw you in quietly but firmly. As Olnick puts it, “What I love about Arte Povera is that it wants the viewer to become part of the work, and you can see a clear connection to that in this show.”