May 4, 2015“The weavings retain a kind of energy, which I feel partially comes from the laborious process of making,” says Canadian artist Brent Wadden of his signature works (photo by Leandro Justen/BFA). Top: New Wadden compositions currently on view at Mitchell-Innes & Nash in Manhattan. All photos courtesy of Mitchell-Innes & Nash unless otherwise noted

The work of Canadian artist Brent Wadden defies classification. His abstractions borrow from diverse traditions and techniques, drawing elements of folk art, Art Brut, Abstract Expressionism, minimalism and Bauhaus design into vibrant compositions that are shaped as much by their quirks and eccentricities as by their formal harmony. Although he considers them paintings, his more recent creations often don’t involve much paint — and might be more accurately described as canvas-mounted weavings, created on a floor loom with acrylic yarns and hand-spun wools.

Born on a small Nova Scotian island and now based between Vancouver and Berlin, the 36-year-old Wadden knows his way around the art of the stitch — a skill that has all but disappeared from contemporary life — and his work embodies a process of negotiation between new forms and old methods. He was exposed at a young age to the customs of his province’s folk artists, who immortalized their cultural narratives of land and sea in decorative objects they made by hand; his subsequent education at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, known as a breeding ground for conceptual art, introduced him to an entirely different visual and technical vocabulary. Since graduating with a BFA in 2003, he has honed a distinctive style that wryly integrates his dual artistic foundations.

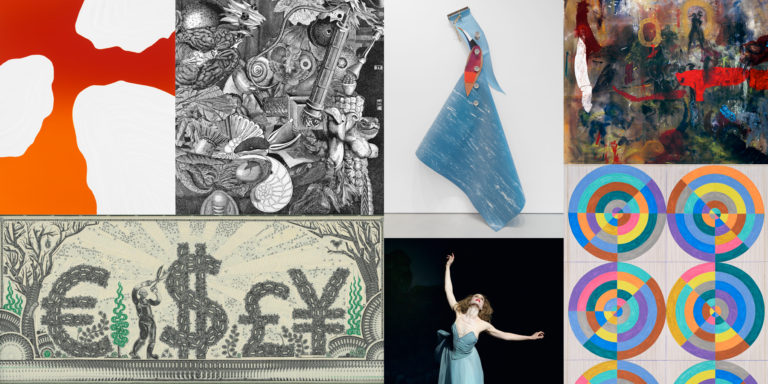

In Blue Wine (left) and Pink and Brown (all works are from 2015), Wadden experiments with form and scale, giving the initial impression of symmetry — but a closer look reveals subtle variations.

The works on view reduce shape and color to its essentials; vertical columns of dark peaks in Big BW evoke a range of art movements and techniques, from Impressionism to minimalist sculpture.

On view at Mitchell-Innes & Nash in Manhattan’s Chelsea through May 30, Wadden’s first major solo exhibition in this country presents a new suite of his humbly hypnotic “paintings,” whose initial visual impression belies their complex underpinnings. Indeed, while the superficial organization of these large-scale, wall-hung works references the cold, logical rigor of Geometric Abstraction, the rawness of their handiwork — loops of natural fibers delicately interwoven — pays homage to the artisanal. Hovering between flatness and depth, order and improvisation, each composition features a series of panels that the artist makes individually and then stitches together, orchestrating compelling dialogues between loosely delineated triangles, stripes and the rounded curves of soft parallelograms.

The eight works on view, all from 2015, evidence the refinement of Wadden’s process; reduced to simple rudiments of color and form, they acknowledge a range of traditions, from grounded to lofty. There are numerous references to the art of indigenous peoples — 5 Green Bars (double fade) concentrates the essential aesthetic and palette of Southwestern American Indian art — and to institutionally canonized art-historical moments like Op Art. Blue Wine and Tangerine Grey (double fade) recall that movement’s trippy visual matrices, while the gentle slopes of the central forms in Pink and Brown, despite their fine modulations of rosy skin tones and chocolates, evoke the stark, black-and-white tessellations of Bridget Riley’s “Winged Curves” series. Wadden looks even further back at times, as well: Though they may hardly be described as impressionistic, the horizontal assembly lines of ebony peaks in Big BW could be a graphic interpretation of Monet’s iconic Haystacks.

Wadden’s compositions are marked by an unpredictable and original use of color; in Tangerine Grey (left), ochres and oranges evoke the gradient of a sunset, while Black Robins Egg Blue features inconsistent swathes of various beiges.

Shaped by subtle modulations of color that give the impression of depth, the abstract forms in Avocado Salmon seem to simultaneously intrude into and retreat from the gallery space.

Despite the rawness of their material, there is a surprising delicacy to the paintings’ surfaces, as the artist’s masterful cadences in color operate precisely the way shading does in painting — giving the impression of physical heft. Here, too, Wadden is appealingly inconsistent, his logic not always apparent. In Tangerine Gray (double fade), firey oranges emulate the perfect gradient of a desert sunset as it approaches the earth, while the various beiges in Black Robins Egg Blue suggest that the artist may have switched spools mid-stitch. The subtlety of these variations feels as intentional as it does serendipitous, presenting an original interpretation of “handmade” that is a welcome aberrance in a market driven by high production values and outsourced labor.

Ultimately, it is something of a marvel that each of Wadden’s compositions manages to operate as a balanced whole despite its constituent parts and myriad antecedents. There appears to be a hint of symmetry in Avocado Salmon, for example, but closer inspection reveals none. In fact, the visibility of seams throughout the show, and the not-quite alignment of the woven panels in any given work — shapes mirrored across them with delicious imperfection — contribute, perhaps paradoxically, to a sense of overwhelming resolution.