December 4, 2013Liberman painted this self-portrait in 1936, when he was living and working in Paris. Courtesy of the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

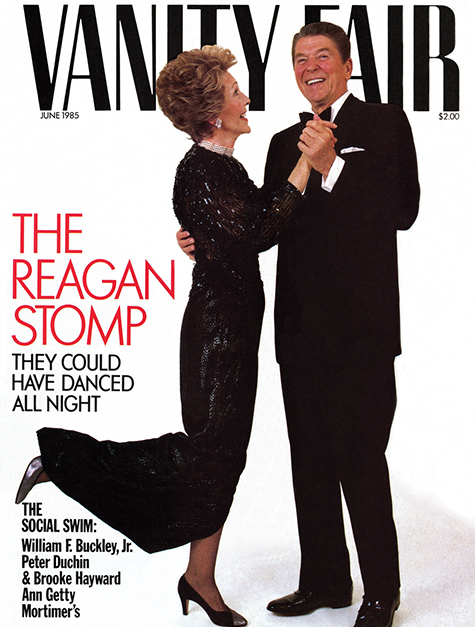

Most of us accept the inimitable style of Condé Nast magazines as fact; we regard the aesthetic aplomb vested in Vogue, Vanity Fair and the rest as an enduring, overarching visual signature, without a singular source or point of origin. But in reality, much of Condé Nast’s success as a modern style arbiter can be traced back to one man, Alexander Liberman, who worked for the company for more than 50 years, first as an art director and then, until his retirement in the 1990s, as the publishing giant’s editorial director, overseeing the look of all its titles. (He died in 1999.) A recognized artist in his own right, Liberman proved a hugely influential force both within the company and in the larger media world, and it’s this story that Charles Churchward — a former Vogue design director who worked under Liberman for more than two decades — captivatingly captures in his new book, It’s Modern: The Eye and Visual Influence of Alexander Liberman, just released by Rizzoli.

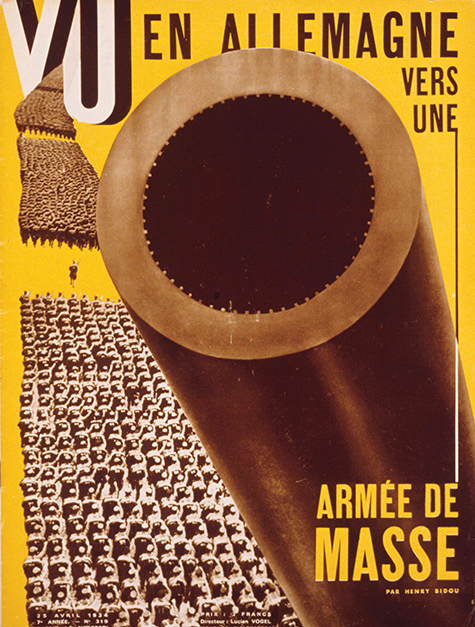

Liberman was born into a comfortable family in the Ukrainian capital of Kiev in 1912. His father was in the timber business; his mother was a theater director who employed Constructivist artists to create her sets. They emigrated to Moscow, and then, at age nine, Liberman was sent to boarding school in London. He later joined his family when they fled Soviet Russia for Paris, where he attended the École des Beaux-Arts, became transfixed by the famously influential Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in 1925 and, through his well-connected mother, met artists Jean Cocteau, Marc Chagall and Fernand Léger. (Throughout his life, Liberman displayed a talent for being in the right place at the right time and knowing the right people.) At age 19, he began working in the art department of the French weekly Vu, the first newsmagazine to be illustrated primarily with photography. It’s Modern includes early examples of the Liberman-designed covers, many of which he laid out in a Constructivist style, often using collage, in dramatic visual strokes. These were all profound experiences that formed traceable visual themes throughout his career.

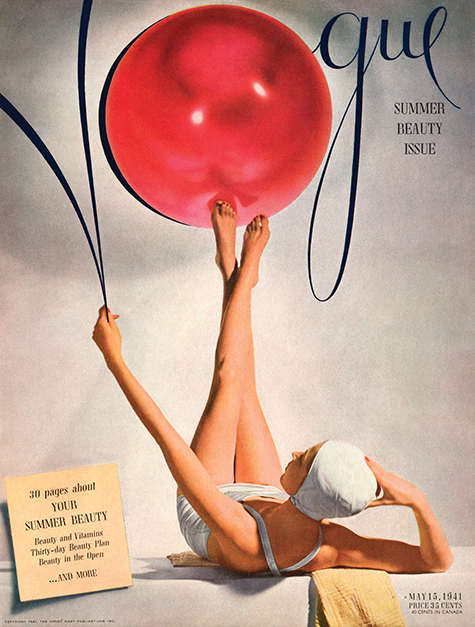

Liberman decamped for New York during the early stages of World War II, with fellow Russian Tatiana du Plessix, who later became his wife, and her daughter, Francine, in tow. Together, they drew on all the fellow immigrant contacts they had, and, in 1941, Liberman, with Vu’s avant-garde layouts to recommend him, landed a job in the art department of Vogue. Du Plessix also started work almost immediately, designing hats for Henri Bendel, and moving a year later to Saks Fifth Avenue.

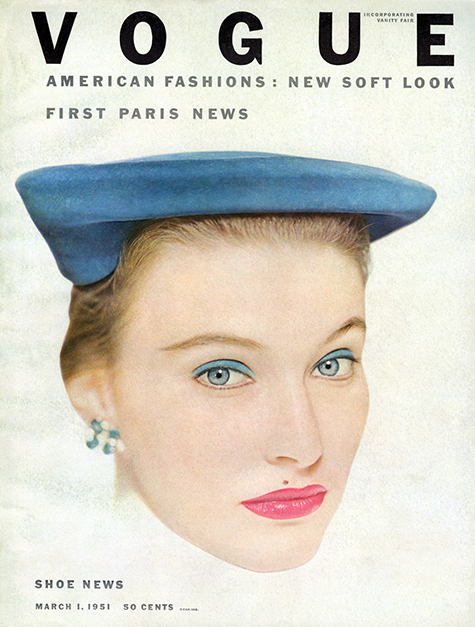

As soon as he was settled at Vogue, Liberman used all his spare time to fulfill his early fine-art promise, and this both formed the underpinning of his magazine work and served as a strong separate career. “His art is important,“ explained Churchward in a recent interview. “And it changes over the years. If you really look at the paintings, he’s always a couple of years ahead of his time.” His work as an artist informed everything Liberman did at Condé Nast, and it contributed to the magazines’ sense of style — a particular aesthetic that resonated with a modern, educated, curious and (mostly) female readership.

Churchward seamlessly weaves together Liberman’s two vocations, depicting both his fine-art work — he started as an abstract painter then moved into large-scale sculpture and photography (his estate is represented by the New York gallery Mitchell-Innes & Nash) — and his Condé Nast oeuvre, including some of the finest magazine work produced under his supervision: fashion photography by Irving Penn, Richard Avedon and Helmut Newton; commissioned art by Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg; and Liberman’s own photos of modern masters such as Paul Cézanne and Georges Braque. “No one ever compared his visual growth in both fields, and the design did go hand-in-hand with his art,” explains Churchward.

Why do a book on the legendary art director today? “It just seemed like the right time,” Churchward says. He pauses, then adds: “I hope to influence young designers, to show them what such creativity used to be, and maybe they will form some ideas about how to bring it back.”

PURCHASE THIS BOOK

or support your local bookstore