June 17, 2022If a single figure could be said to represent the entirety of the current Venice Biennale, it might be Cecilia Vicuña. More than any other figure, the 74-year-old Chilean artist and activist seems to embody the event’s key themes, defined by curator Cecilia Alemani as “symbiosis, solidarity and sisterhood.”

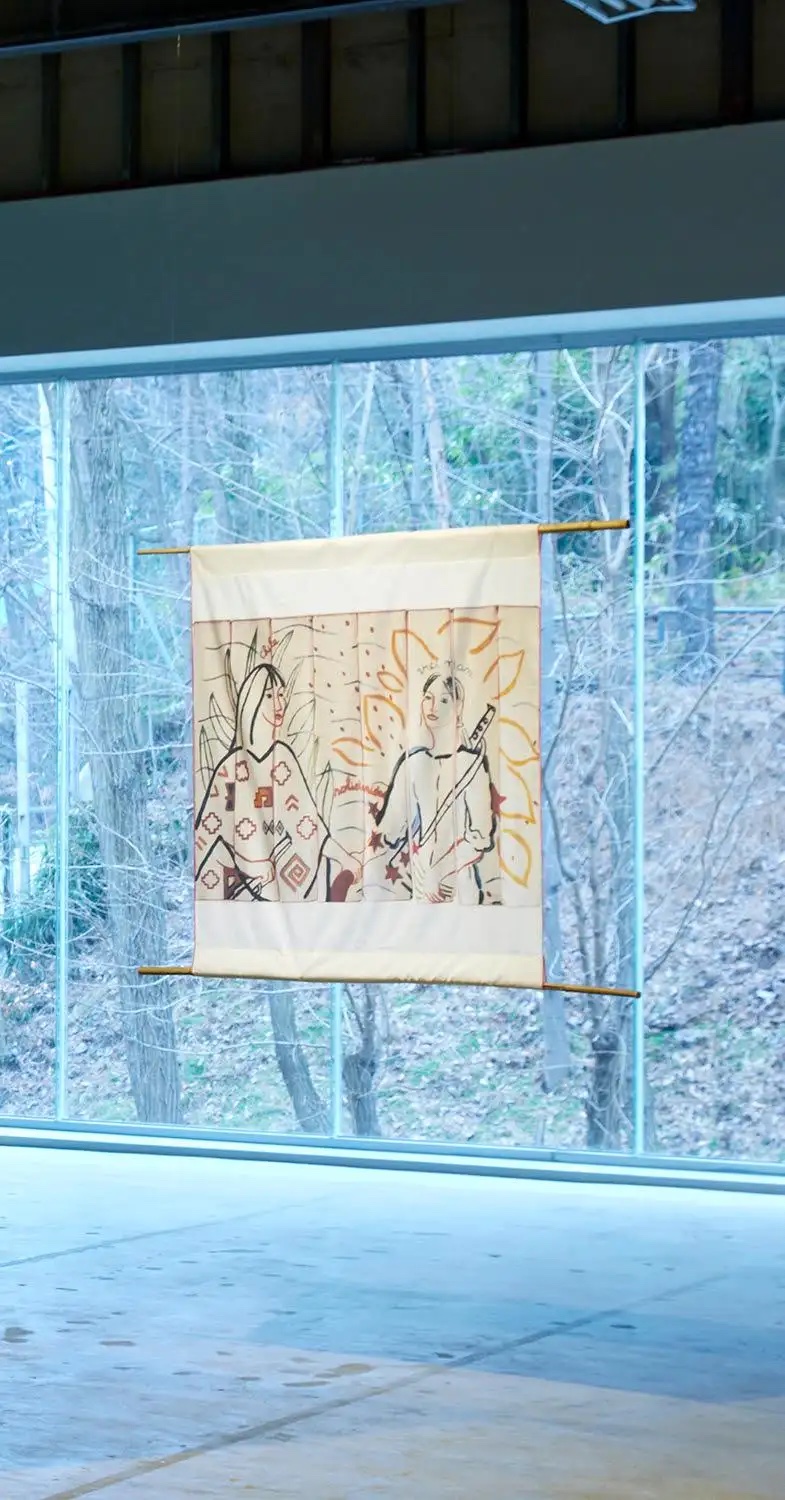

Over the course of decades spent in exile, Vicuña has created a body of work spanning surreal portraiture, word-based printmaking, monumental textile sculptures and flag-like banners. Through these pieces, she has passionately and persistently addressed issues that only now are being taken up with similar urgency across the art world — among them, Indigenous knowledge and spirituality, gender and sexual diversity, climate change and scientific innovation.

Those topics are also front and center in her new exhibition, “Cecilia Vicuña: Spin Spin Triangulene,” on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through September 5. It is the first survey of her work by a New York museum, even though the city has been her home since 1980.

Born in Santiago, Chile, Vicuña exhibited at the National Museum of Fine Arts there and was well known in activist circles by the early 1970s. When a military coup ousted democratically elected Chilean president Salvador Allende in 1973, while she was studying in London, she sought asylum in England. After a few years there, she moved to Bogotá, Colombia, before settling in the United States.

Vicuña has made regular appearances over the years in important group shows like the 1997 Whitney Biennial, the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art 2007 exhibition “WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution” and the 2017 edition of documenta. But the coinciding exhibitions in Venice and at the Guggenheim — as well as a prestigious commission for Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall to be unveiled in October — signal a new level of appreciation for her art. So does the biennale’s presentation to her of the prestigious Golden Lion award for Lifetime Achievement.

“At the moment there is so much confusion, so many questions, and the persistence of somebody like Vicuña is needed,” says Rachel Lehmann, cofounder of Lehmann Maupin gallery, which represents Vicuña and has been instrumental in bringing wider attention to her work in recent years.

The title of the Guggenheim show refers, somewhat cryptically, to the triangulene molecule. This microscopic mound of carbon atoms, assembled in a recent feat of laboratory engineering, has potentially significant applications in electronics. Vicuña, however, seems more interested in the poetic and symbolic resonance of the molecule’s double spin. “Becoming aware of the spirit-spin that weaves us together, we enhance our chance of survival,” she writes in a statement for the exhibition.

Vicuña’s signature textile works, titled Quipus, embody the insight that contemporary scientific discoveries like the triangulene molecule often mirror ancient Indigenous practices. The Quipus, made from a combination of unspun wool and found objects, are based on traditional Andean weavings of the same name that used sophisticated systems of knots to encode important stories and other pieces of information.

An installation view of Biombo casita para pensar qué situación real me conviene (Little House to Think What Real Situation Suits Me), 1971, at the Guggenheim. Photo by David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2022

“This is what Cecilia has been trying to do all along, to show the connections of previous cultures to science and knowledge,” Lehmann says. “Many cultures had this knowledge way before we knew about anything. It’s about this continuation.”

The Guggenheim show includes a haunting new three-part Quipu, commissioned for the exhibition. Quipu del Exterminio (Extermination Quipu) suspends found objects, including branches, shells, seeds and amulets, in tangles of wool, plant fiber and horsehair. It evokes both the fragility of life on earth and the interconnection that may yet sustain us.

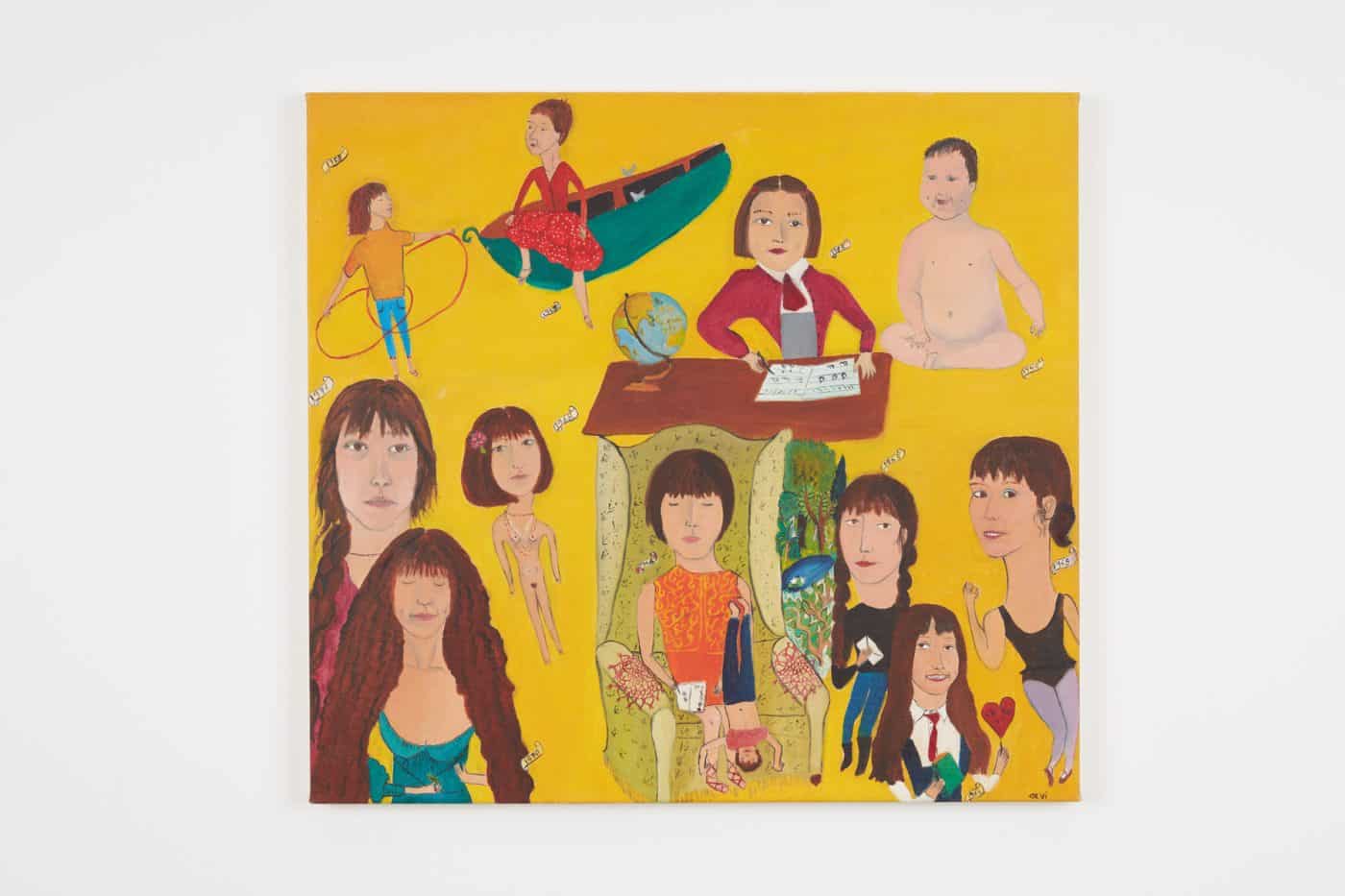

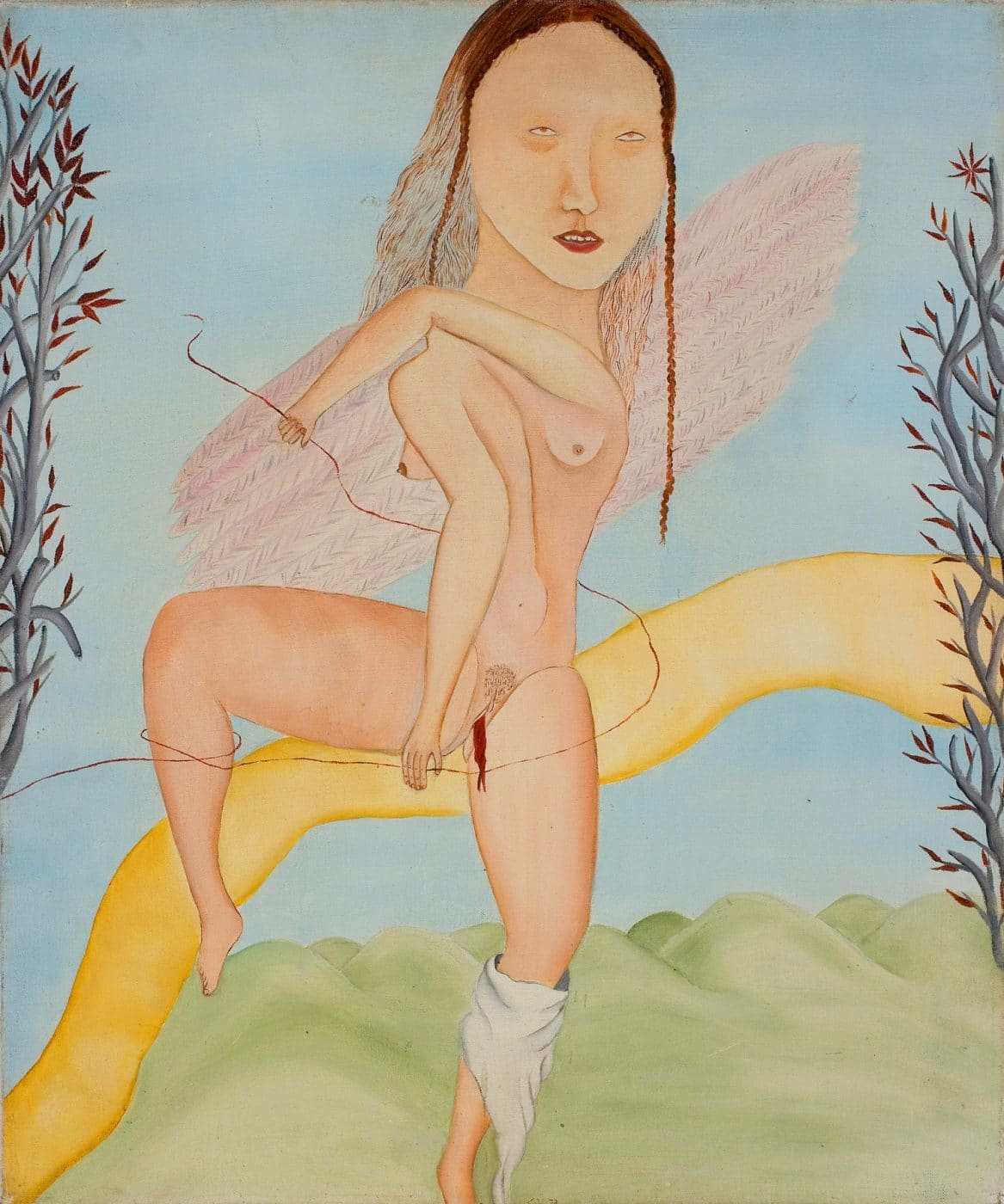

The exhibitions in Venice and at the Guggenheim also highlight Vicuña’s bold and colorful paintings. In these, she depicts real and imagined figures — including herself and fellow activists, along with animals and mythological creatures — in a style loosely influenced by Surrealism and Social Realism.

The delightful self-portrait La Vicuña (1977), prominently displayed at the Guggenheim, can be seen as an avatar. It shows the artist sitting triumphantly astride a vicuña, a wild Andean camelid whose wool was prized by the Incas.

Several other works celebrate Indigenous female leaders like María Sabina, a Mazatec healer and poet who is now hailed as a pioneer of psychedelic medicine, and Elisa Loncón, a Mapuche linguist and eco-political activist in Chile.

Many of these paintings have only recently come to light. Lehmann recalls that on her first visit to Vicuña’s studio, in 2017, the artist had a corner stacked with unframed canvases. In Chile, during the repressive dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet that followed the coup, exhibiting Vicuña’s art was dangerous. A Santiago museum director stashed her portrait of Karl Marx (now on view at the Guggenheim) in his house to keep it safe from police raids, even going so far as to paint Charles Darwin’s name over Marx’s.

In “Spin Spin Triangulene,” Vicuña’s activism extends to an inspired critique of the Guggenheim’s own history. The new painting Three Spirals and an accompanying statement link the museum’s Frank Lloyd Wright design to the curved ramps of the Chuquicamata copper mine in Chile (owned in the early 20th century by the Guggenheim family) and a conch-shell trumpet of the type used in sacred Maya rituals. Her point is that the museum owes a material and creative debt to Indigenous people.

“Vicuña’s Three Spirals links her own biography with that of the museum in a meaningful way that also calls for reflection on our own histories, while at the same time connecting them to Andean Indigenous knowledge and spirituality, important terms in her artistic practice,” says Geannine Guimaraes, associate curator of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, who organized the New York exhibition with the Guggenheim’s Latin America curator at large Pablo León de la Barra.

Vicuña traces much of what we consider modern architecture, technology and design back to Indigenous culture— and to the innovations of women, in particular. It’s an argument that current-day technocrats would do well to remember.

“In my view, architecture evolved from a moment when women observed that animal hair and vegetal fibers spiraled, spinning of their own accord,” she writes. “This insight allowed them to spin the first cords. Then, they could tie together sticks, imitating bird’s nests and spider webs. The first cross-stitches uniting vertical and horizontal twigs and fibers allowed for all weaving and architecture to emerge. Human hands mirroring the cosmic spin, as observed in the spiraling galaxies visible in plain sight.”