February 10, 2019A major renovation and expansion project at Colonial Williamsburg‘s folk and decorative arts museums has put a new focus on the Virginia historic site. The institutions’ holdings include this 1780 portrait of George Washington by Charles Willson Peale (photo courtesy of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg). Top: The Governor’s Palace in Colonial Williamsburg (photo courtesy of Colonial Williamsburg)

With a historic area that sprawls over 300 acres and includes many meticulously restored structures, Colonial Williamsburg is far more than the destination at the end of a long-ago family car trip. Yes, the buildings are old and charming, and the “residents” dress in bonnets and other period paraphernalia. But this National Historic Landmark and living history museum devoted to 18th-century Virginia life and America’s beginnings also boasts an impressive endowment (upwards of $700 million as recently as 2017) and welcomed some 600,000 visitors last year. Chief among its attractions are the two on-site art museums: the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum and the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, both exemplars of their fields.

Located next to each other, the sibling institutions feature treasures like Charles Wilson Peale’s iconic 1780 portrait of George Washington and the silver teapot owned by Virginia’s last royal governor, John Murray, as well as numerous masterpieces by self-taught artists and artisans, from paintings (the early 19th-century Baby in Red Chair is a popular favorite) to quilts.

From time to time, history needs a spit and polish, just as a teapot does. So these two museums are undergoing a $41.7 million expansion and renovation, due to be completed next year. The project will add 60,000 square feet of exhibition space and, most notably, revamp the entrance, lobby and orientation areas, providing a new restaurant and shop. Tradition suffuses the place even as it moves forward: When ground was broken on the new facilities, designed by New York’s Samuel Anderson Architects, officials used replicas of 18th-century shovels.

The overhaul, led by Colonial Williamsburg CEO and President Mitchell Reiss, included hiring art world veteran Ghislain d’Humières as executive director and senior vice president of core operations, which encompass the museum collections, conservation and historical interpretation. The French-born d’Humières started in the position last year, after leaving the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Kentucky, where he had spearheaded the funding and construction of a striking $60 million addition by the architect Kulapat Yantrasast.

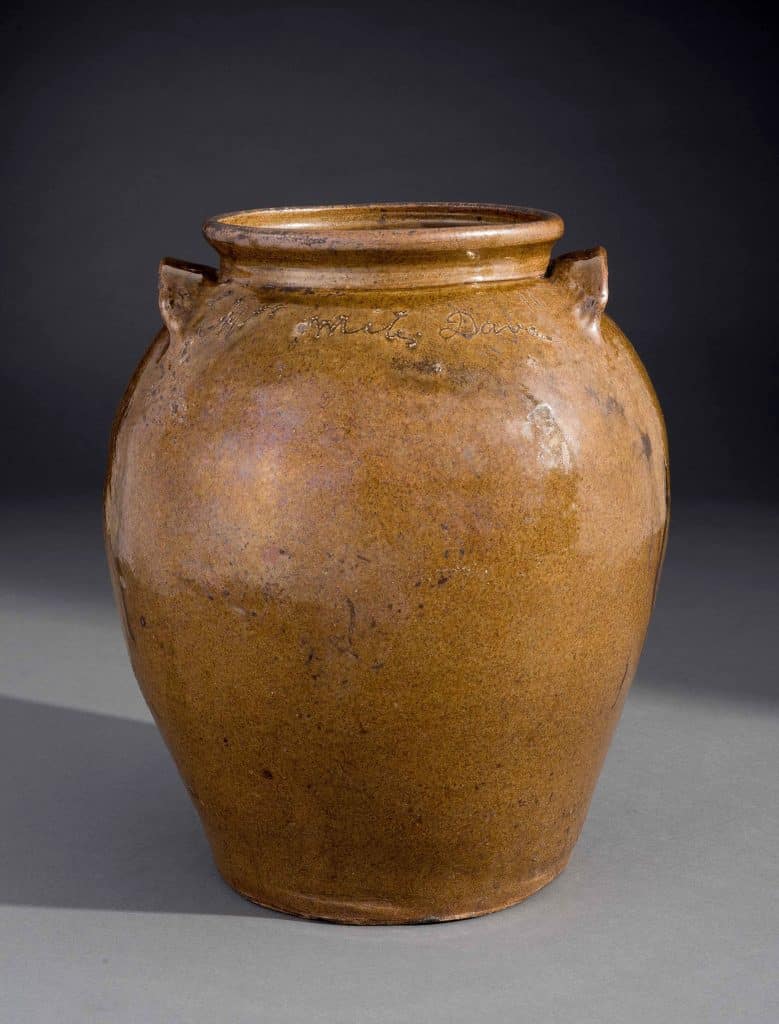

“A Rich and Varied Culture: The Material World of the Early South” — a long-term exhibition at the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum — shows off objects, furniture and art from several regions of the southern American colonies. Photo courtesy of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg

As museum chiefs go, d’Humières has had a somewhat unconventional career. Before his stint in Louisville and his preceding post as director of the University of Oklahoma’s Fred Jones Jr. Museum, he worked at both Christie’s and Sotheby’s in the market-oriented part of the art world.

“It’s only a small shift from art history to history itself,” d’Humières remarks of his transition from the Speed to Colonial Williamsburg. His new job is about three times as big, involving the oversight of nearly 1,000 employees.

French-born Ghislain d’Humières was recently appointed head of Colonial Williamsburg’s art museums, overseeing their collections, conservation and historical interpretation. Photo by Chris Humphries

As it happens, the time period he’s now engaged with is not totally foreign: He was an 18th-century specialist in graduate school — albeit in French decorative arts. Asked to cite a favorite object in the Wallace’s collection, he mentions a George III clock inlaid with bronze. “I guess I like it because it’s French,” he says with a laugh.

But d’Humières is serious about the substantial holdings he now oversees. “Both museums are world-class,” he states. “Our folk art museum is by far the best such institution in the country, and the Wallace’s English and decorative arts pieces are as good as the Met’s. People may not know about them, though.” Having taken charge of communications, he aims to correct that.

D’Humières may be a newcomer, but Carlisle H. Humelsine Chief Curator and Vice President for Collections, Conservation and Museums Ronald L. Hurst has been on staff for 38 years, and he sees the coming changes as bringing a deserved spotlight to the fruits of a lifetime’s hard work. He points out that with 70,000 objects of folk art and decorative arts between them, the two museums can dive more deeply into material culture than most other institutions.

“In the decorative arts, we own both British and American pieces from 1670 to 1840, and we’re the only place that collects the full range of American, from Maine to Louisiana,” Hurst says. “The regional differences are profound. It’s been our mantra from the beginning to cover a wide geographic spectrum. No one else does that.”

Aesthetic and stylistic characteristics find echoes among the various collections, interconnecting them. “You see the ethnic influences,” Hurst says. “The French influence on Louisiana furniture is palpable. And the German influence on what’s made in the Shenandoah Valley.”

Colonial Williamsburg, moreover, is not just sitting on a trove. Hurst notes that it also still actively buys some 300 works a year, such as the 1829 schoolgirl sewing sampler he just acquired from Detroit.

With the new spaces coming in 2020, “we’ll have the room to do what we need to do,” he says. The flavor of the exhibitions has always been “no art historical jargon, just completely digestible information. It’s not enough to say, ‘This is an important Philadelphia chair.’ We tell people why they should care. We string the objects together in stories, and one object may have ten different roles in ten different exhibitions.”

This ca. 1700 tall English case clock by Thomas Tompion is, according to the DeWitt Wallace museum, “the most important clock in the Colonial Williamsburg collection and possibly in North America.” Made for William III of England and owned by all succeeding English monarchs through Queen Victoria, it was acquired by Colonial Williamsburg in the mid-1950s for the Governor’s Palace. Photo courtesy of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg

To illustrate, Hurst points to a double chest of drawers from Charleston crafted between 1765 and 1780 from mahogany, cypress and poplar. “It’s the finest example of the form from the Carolinas, with all the bells and whistles,” he says. “But this is made by a British immigrant right during the time of the Revolution — there are so many facets here.”

For at least a decade or two, art museums have been at pains to appeal to younger, more diverse audiences and to provide “experiential” content of all stripes. Oddly, this puts Colonial Williamsburg — a traditionalist bastion founded in the 1930s largely with Rockefeller family support — ahead of the curve: What could be more experiential than historic re-creations enlivened by real people playing parts?

D’Humières relishes this twist. “Working in the historic area, dealing with actors — it’s been my biggest challenge, but completely fascinating,” he says.

And, he points out, it’s of a piece with his experience: “Making sure that the mission is relevant for the next generation, that’s the thing I’ve been doing my whole museum life.”

With his French heritage, d’Humières, who just recently became a U.S. citizen, has an outsider’s perspective that often leads to big-picture clarity. At Colonial Williamsburg, he says, “we’re here to show Americans who they are.”