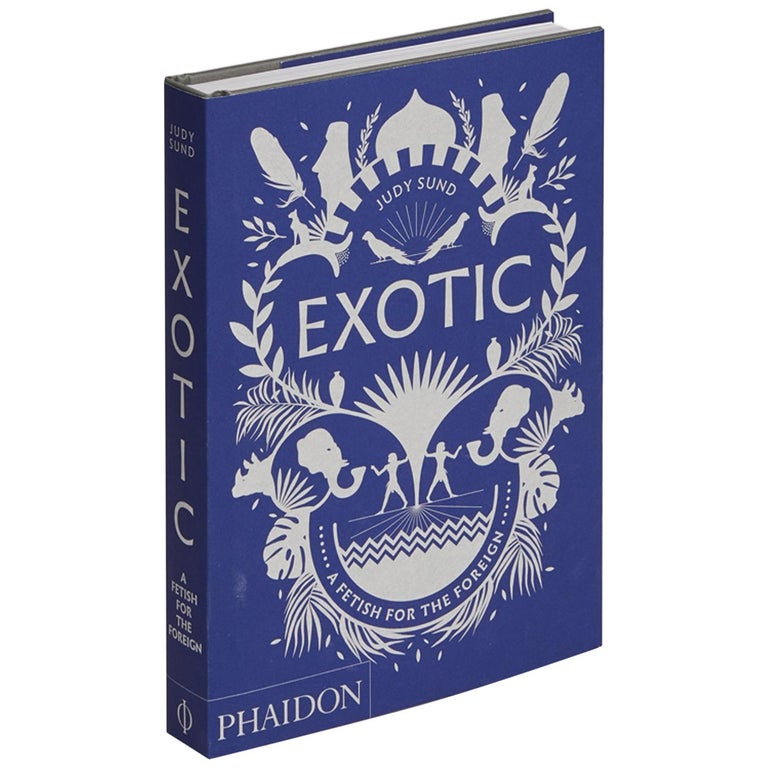

June 9, 2019Written by art professor Judy Sund, Exotic: A Fetish for the Foreign (Phaidon) shines a spotlight on our fascination with the “Other” across time and geography. The book’s examples include British painter George Romney’s 1776 portrait of the Mohawk Joseph Brandt (née Thayendanegea) in English garb (photo courtesy Granger Historical Picture Archive/Alamy Stock). Top: For his representation of America in Versailles’ Salon of Apollo, Charles de La Fosse borrowed the feathered ceremonial dress of indigenous Brazilians (photo © RMN-Grand-Palais / (Château de Versailles) / Gérard Blot).

Judy Sund is a daring scholar. In her new book, Exotic: A Fetish for the Foreign (Phaidon), the City University of New York art professor takes readers on a fascinating journey around the globe as she explores the history of that word, whose definition has always been, as she puts it, “slippery,” and whose meaning today has become politically fraught.

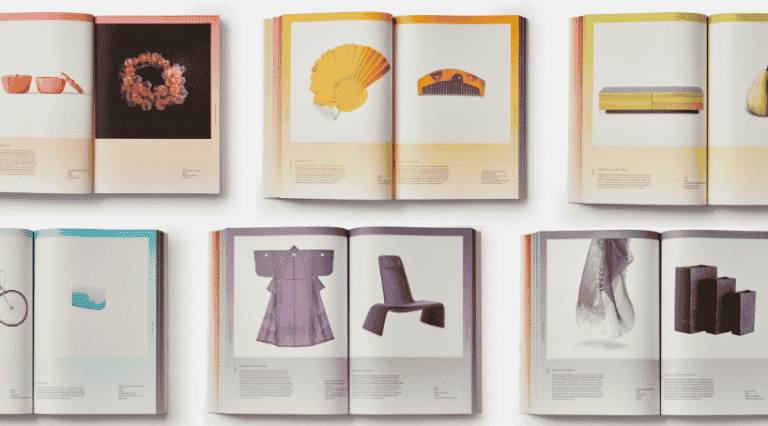

Yet, as she argues with wit, intelligence and myriad examples, from the erudite to the pop, in this gorgeously illustrated book, the exotic is integral to our understanding of Western visual culture — and particularly, I might add, of the decorative arts.

If you think the notion of the exotic arose during the Age of Exploration, when the discovery of new lands and sea routes — and the riches and marvels they offered — brought out the darkest colonizing impulses in European nations, think again.

As Sund tells us, the practice of “exoticism” — the process of turning the products of another culture to one’s own purposes, be they aesthetic, commercial or, for that matter, political — is not unique to the West.

The motives “may vary, and sometimes overlap,” she says. “But the processes of co-option have been remarkably consistent and are traced in my book through numerous intercontinental examples.”

These are often surprising. The most ancient visual record Sund cites is a set of temple reliefs at Deir el-Bahri, near ancient Thebes, dating to 1493 BC. They portray an Egyptian expedition sent by the female pharaoh Hatshepsut to the Land of Punt, probably located somewhere south of the kingdom on the Red Sea littoral.

There, according to Sund’s book, the visiting Egyptians acquired gold, frankincense, myrrh and animal skins. The reliefs also depict Egyptian ships departing with baboons and uprooted trees for the pharaoh’s exotic menagerie and temple.

So, it seems a taste for the curious and rare is not a Renaissance phenomenon — as one might have thought with that era’s predilection for assembling Wunderkammern — but positively primeval.

Below, Sund talks about several of the most captivating revelations in her book.

“Tents were a time-honored offering from Eastern rulers to Western counterparts,” Sund writes. In the 18th century, these shelters — such as the painted-copper 1787 version by Louis-Jean Desprez shown here, in Solna, Sweden’s Haga Park — “were erected in Asian-style gardens across northern Europe.” Photo by Robert Matton AB / akg-images

Johann Joachim Kändler, Meissen‘s chief modeler at the time, crafted this porcelain figure of a Turk riding a rhinoceros around 1752. Rhinos enjoyed a European vogue in the middle of the 18th century after one was brought from Bengal to Rotterdam on a Dutch trading ship and toured around the Continent — “as a myth come to life: a ‘real unicorn,’ ” Sund writes. Photo by Stefan Rebsamen / © Bernisches Historisches Museum, Bern.

1. At a moment when discussions about the validity of cultural appropriation often dissolve into vitriol and outrage, you’re courageous enough to delve into the history of a word that elicits the worst of those tendencies. Clearly you have a message for us about the complex role that the “Other” has played in Western civilization.

Exoticism, as a practice, dates to the earliest interactions between groups that perceived one another as unalike. The Other — a concept that’s relative, of course — has proved both fascinating and unsettling. And exoticism is described here as a means of negotiating difference and responding to a recurring question: What to make of that which is unaccustomed, even alien?

Although all exotics derive from that which is foreign, not everything foreign is exotic. Only people and products that are judged useful are “brought home,” and once displaced and relocated, most are tweaked — “improved,” “adjusted,” “enhanced,” drained of original meaning and/or fragmented — and repurposed.

The resultant exotics often inspire takeoffs and, over time, may become so enmeshed in the appropriating culture that they lose their foreign connotations. But exotics — overtly or undercover — enrich the appropriating culture and contribute aesthetic dynamism, no matter how they are deployed.

2. Many of our readers may know that the word “exotic” is derived from Greek, but I’m not sure how many are aware that the Greeks “exoticized” Persians and sub-Saharan Africans, whom they called Aethiopians, meaning “charred by the sun.”

Aethiopians were prized servants because they were so different looking as to be immediately recognizable as Other and were relatively rare. Novelty and rarity are bywords of the exotic. The possession of that which is rare confers status.

Aethiopians were regarded in the same way exotic animals were: as marvels to be gaped at. Persians, by contrast, were not themselves as exotic as Aethiopians, but their goods — tents, drinking cups, clothing, et cetera — were valued for their extravagance and novelty.

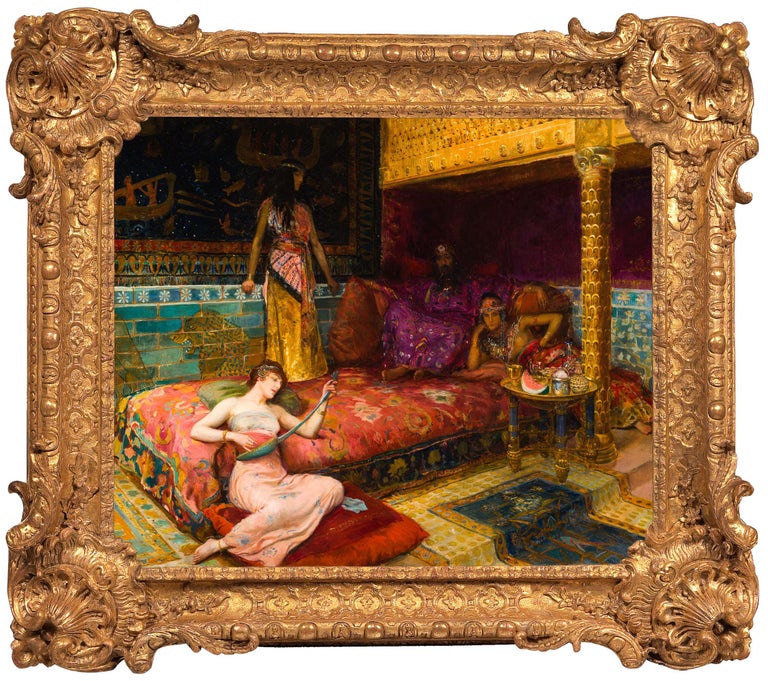

In The Seraglio of the Pug, a 1734 “canine send-up of the Ottoman court,” Sund writes, “Jean-Baptiste Oudry pokes fun at the vacuous pasha even as he acknowledges the desirability of his creature comforts: loose clothing, soft seating and a pipe of Turkish tobacco.” Photo © Audap & Mirabaud

Moreover, the exoticization of Persian goods had a political dimension. Having invaded and attempted to conquer Greece, Persians were seen as aggressive and were vilified. Athenian moralists pointed to their extravagant lifestyles as evidence of Persians’ self-indulgence and the men’s effeminacy.

Women, it should be noted, were the original Other, and exoticism and femininity have often been seen to go hand in hand. The politics of the Persian vogue are especially evident in the remaking of Persian-style drinking horns as comedic vessels for use in Athenian symposia, and in Athenian women’s co-option of clothing and accessories associated with Persian men of high rank, especially fans, parasols and the horseman’s jacket called a candys.

The Egyptian Revival style that swept into fashion following the discovery of King Tut’s tomb in 1922 — dovetailing nicely with the Art Deco aesthetic then the rage, as demonstrated by this 1929–30 Illinois theater by Elmer F. Behrns — was only the latest manifestation of Egyptomania. Sund writes that the craze extends back to “the 7th century BC, when Greeks first coined words for pyramid and obelisk and re-gendered as female the creature they named the Sphinx.” Photo by Brandon Bartoszek

3. I was intrigued by some of the examples in your book of intercontinental exoticism. You explain that the blue-and-white porcelain made by the Chinese started out as an export item not for Europeans but for Muslims in the Middle East. And the distinctive cobalt blue of that “china” came from Persia. Can you elucidate?

One of the book’s takeaways, I hope, is that exoticism is universal. Everybody did it and does it. What’s exotic is relative. In the book’s introduction, I mention how fashion-forward Japanese adopted Portuguese bombachas around 1600. I also note the folding screens on which Japanese artists caricatured Europeans in portrayals that became part of domestic decor.

The blue-and-white porcelain we consider quintessentially Chinese was first developed for export to the Middle East. It featured not only intense blue shades derived from imported cobalt, which the Chinese called huiging, or “Muslim blue,” but Middle Eastern vessel shapes and dense foliate ornamentation.

Because this blue-and-white porcelain appealed — in its novelty — to the imperial court, Chinese ceramists began to make it for Chinese consumers, using imperial motifs like the dragon, and later devised export versions aimed at European consumers.

We may think of Chinese blue-and-white export porcelain as intended for a European market, but it was originally made for Muslim countries and then picked up by the Portuguese, who were the first Continental traders in China. Here, a bowl from the Jiajing period (1522–50) of the Ming dynasty features the coat of arms of Portugal’s King Manuel I, inverted. Photo by Christopher Allerton / Casa-Museu Medeiros e Almeida, Lisbon

Glossy black lacquerwork made in China’s Henan province and embellished with gold and colored incising was christened Coromandel by English traders, after the Indian coast from which it was shipped to Europe. Shown here is the 1740s Coromandel room of Brühl, Germany’s Schloss Falkenlust. Photo by Florian Monheim / Bildarchiv Monheim GmbH

4. I think it’s fair to say that people today who have a Berber rug, a suzani bedspread and a collection of handwoven Balinese temple baskets in their boho chic homes are exoticists. Do you see this craving for manifestations of the Other as distinctively human?

It’s a commonality that spans centuries and continents. In the book, I cite Gervase of Tilbury, who in the thirteenth century wrote a chronicle of marvels and observed that the inherent human craving for novelty led “the old to be changed to something new, the natural into the marvelous, and familiar things into strange.”

Five centuries later, a journalist in London described his contemporaries’ “remarkable greed for novelty, which requires continual feeding with fresh material.” In the modern world, with quicker fashion cycles, exoticists need to be ever more resourceful as they seek to sate our enduring desire for that which is new, unique and oddly alluring.

5. What for you are the most beguiling contemporary examples of cultural appropriation, especially in the realms of interior design, architecture and art.

This is a tough question. I guess I’m intrigued by regional exoticisms — things like “outsider art” and “street art,” which are culled from non-elite spaces to sate elites’ quests for the unusual and “authentic” — as opposed to mainstream exotics that many brand as kitsch.

On the other hand, I’m also drawn to exoticists’ embrace of full-on kitsch in spaces like tiki bars, which are seeing a resurgence years after Ivana Trump rid the Plaza Hotel of its delightful Trader Vic’s in the interests of refinement.