October 9, 2022In the half-century since art historian Linda Nochlin penned the influential 1971 essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” — which condemned institutions for long preventing women from achieving critical and financial success as artists — curators, critics and collectors have worked to raise, relaunch and rediscover the careers of female creators.

Important recent milestones — like the late Swedish abstract painter Hilma Af Klint’s (1862–1944) Guggenheim retrospective, in 2019, which sold more tickets and catalogues than any other exhibition at that museum — point to cracks in the glass ceiling. But gender equality in the art world remains a largely unattained goal. Compared to their male peers, female artists remain underrepresented in museum collections, account for fewer exhibitions and fetch significantly less money at auction.

Inspired by the 50th anniversary of Nochlin’s intellectual call to arms, the editors at Phaidon, in collaboration with writer and curator Allison Gingeras, have compiled the beautiful and impressive new volume Great Women Painters.

Addressing inequities stemming from what Gingeras refers to in the book as “generations of exclusively male tastemakers and gatekeepers,” this revisionist tome presents more than 300 artists who deserve our attention.

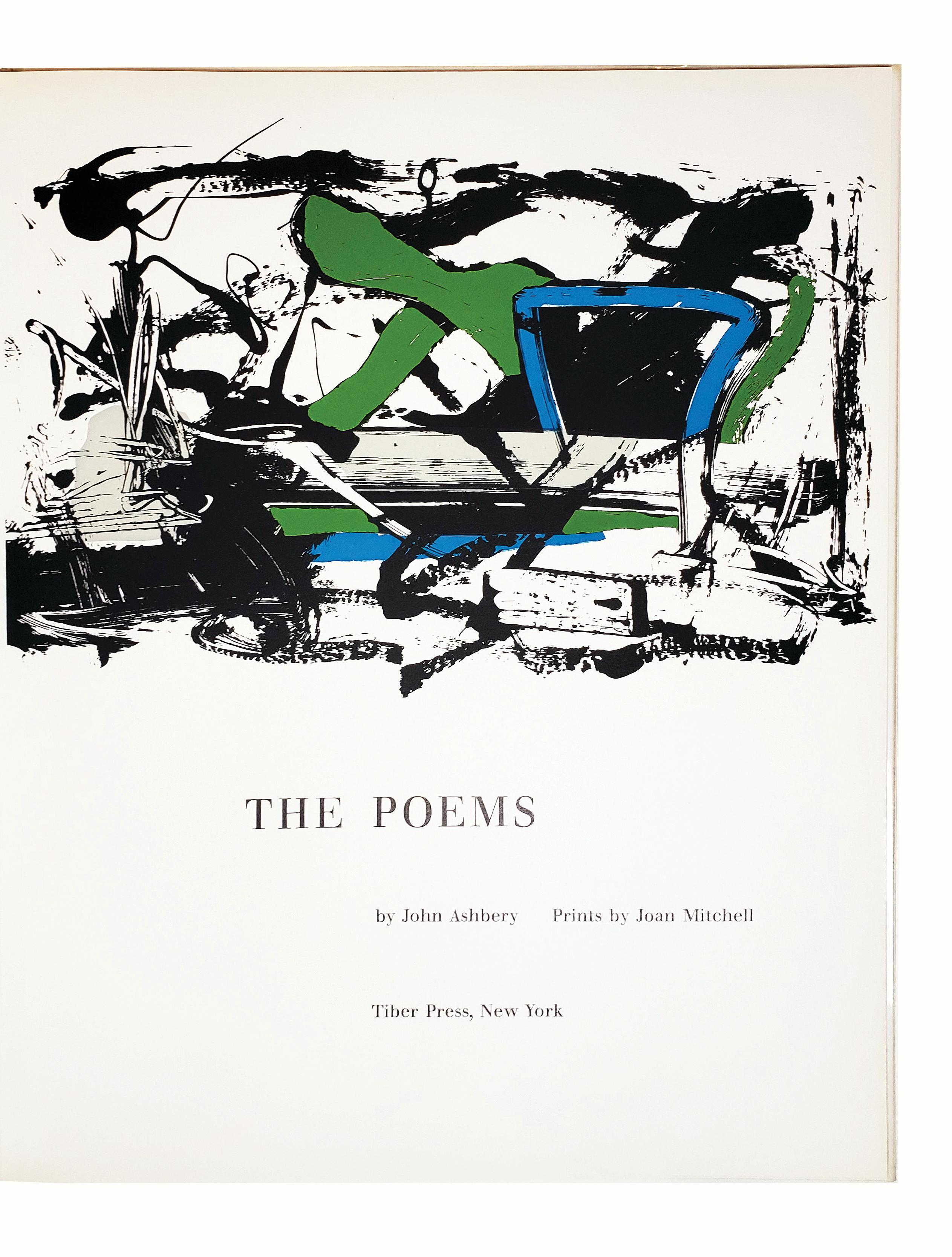

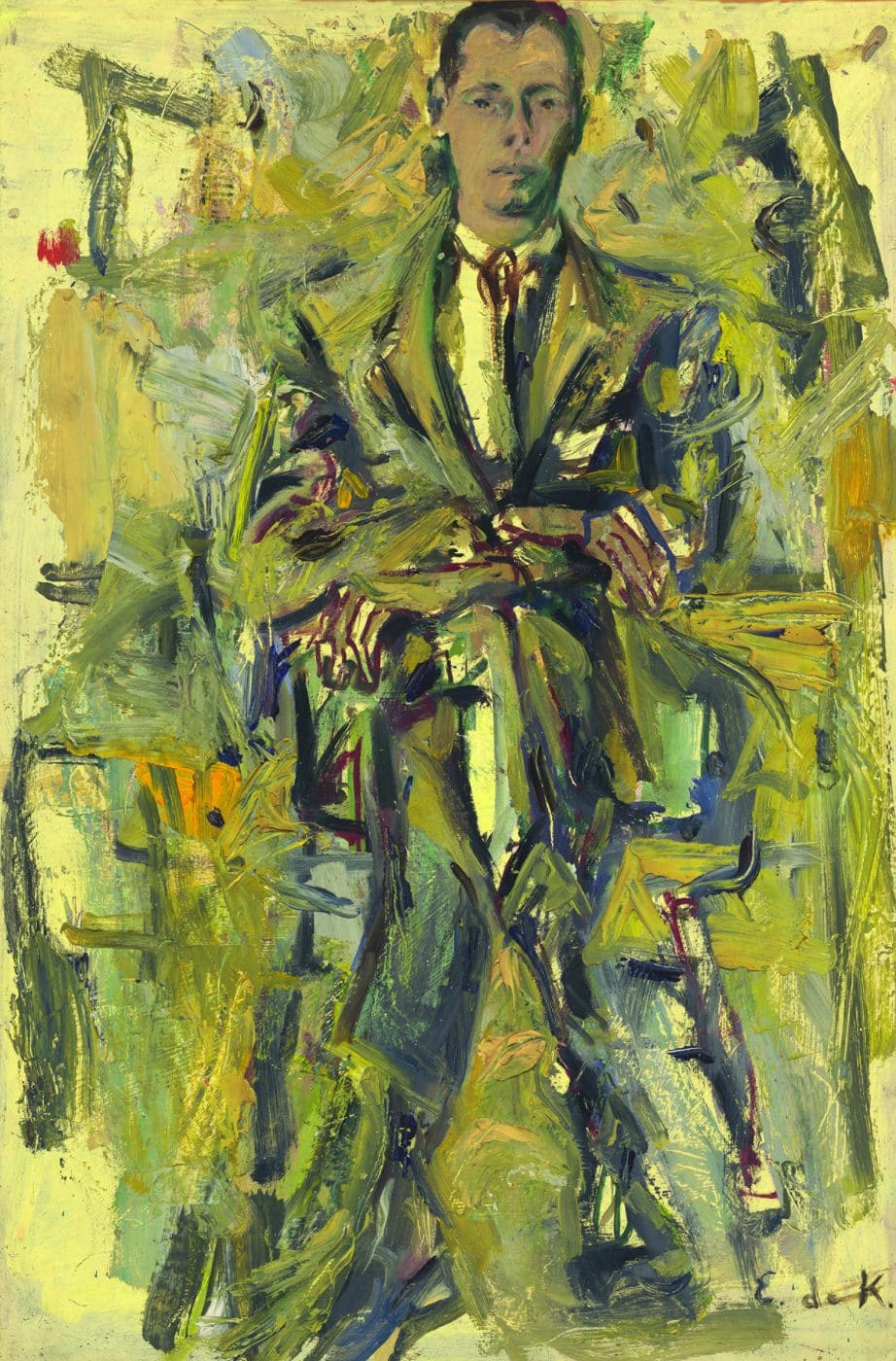

Hailing from all over the world and representing art historical periods from the Renaissance through today, the painters featured in this book include blue-chip names like Rosa Bonheur, Mary Cassatt, Elaine de Kooning, Joan Mitchell, Georgia O’Keeffe and Yayoi Kusama as well as lesser-known talents and those whose most important contributions to art history have largely been written out of the canon.

“Though a fierce defender of Abstract Expressionism” — and its creators, including her husband, Willem — Elaine de Kooning “became best known for her portraits, particularly of men,” Gingeras writes, “and she is credited with having reinvented the modern portrait by combining figuration with an abstract vocabulary.” That blend can clearly be seen here, in 1956’s Tom Hess #1 (art © the artist / National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution / Edek Trust).

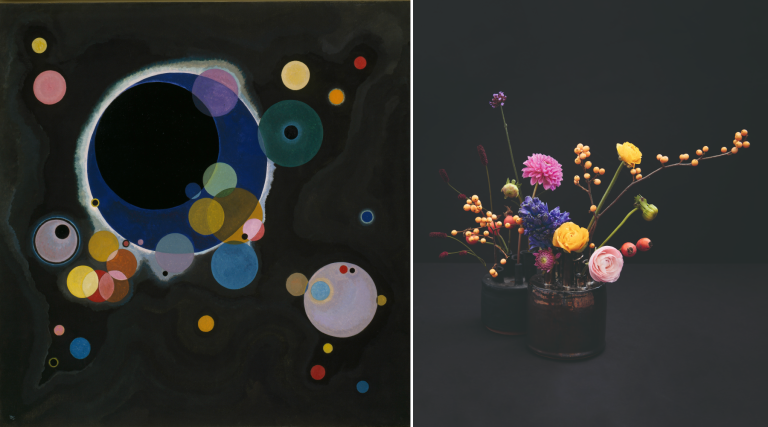

Celebrated in the book for inventing the “soak-stain” painting technique in the 1950s, Helen Frankenthaler was initially dismissed by the art world establishment as too feminine to be taken seriously. “Kotex paintings” is how fellow female abstractionist Mitchell famously disparaged her contemporary’s work. Not until two male artists — Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland — visited Frankenthaler’s studio in 1953 and adopted (stole?) her method of soaking canvas with turpentine-thinned paints did soak-stain become a respected style.

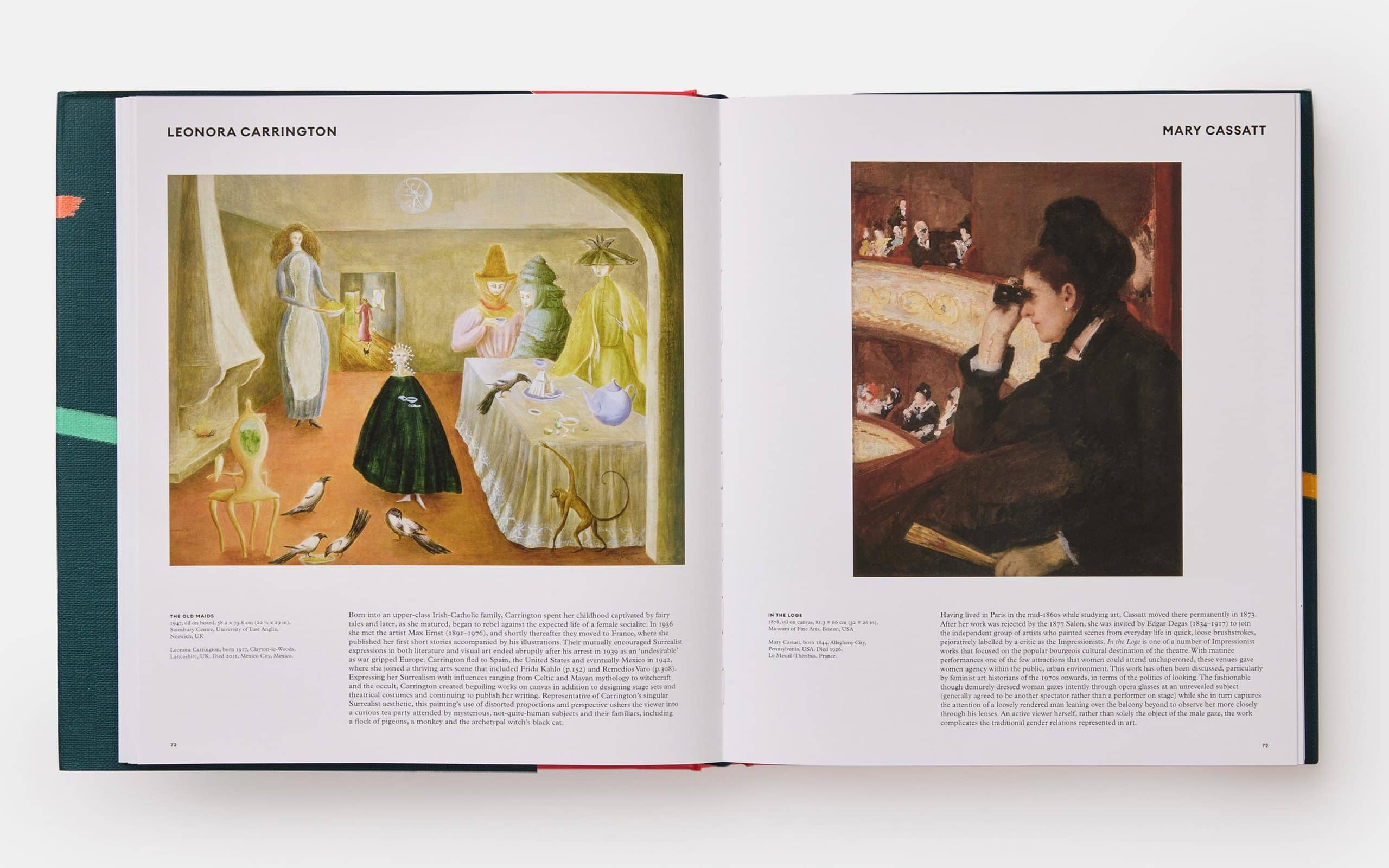

The painters in this book are presented in alphabetical order and each represented by a single painting and brief text that includes biographical details, art historical context and stylistic description. Unsurprisingly, many of the works feature female subjects or so-called feminine subject matter — from pregnant nudes to the Statue of Liberty — which creates fascinating visual dialogues throughout the book.

Take, for example, the juxtaposition of Cassatt (1844–1926) and Leonora Carrington (1917–2011). It makes for a lively tête-à-tête about the traditional roles assigned to women in art and society. Cassatt’s Impressionist portrait of a female opera-goer using binoculars (In the Loge, 1878) is often cited as an early commentary on the “male gaze,” while Carrington’s Surrealist scene (The Old Maids, 1947) depicts a group of women busying themselves with tea and cakes while pigeons and a monkey add to the overall sense of absurdity.

Painted in distinct styles and portraying different subject matter, these paintings find common ground in what they say about the experience of being a woman and an artist. Namely, that men have long held a monopoly as gazers and as absurdists.

Flipping through Great Women Painters provides many such surprising and stimulating pairings. Each spread offers a chance to reconsider, celebrate and compare works by artists of different cultures, working in various artistic styles and across the centuries. As a whole, the book represents a long-overdue opportunity to reinsert these women into the art historical canon.