February 13, 2022Kenyan-born Shiro Muchiri believes passionately in fusing the finest of craft cultures around the world. In her collaborative design practice, she has paired beadwork from Kenyan communities with luxury Italian-made furniture and brought on board indigenous Ainu artisans from Japan, uniting their fish-scale carvings with Italian ceramics.

“The starting point was wanting to involve as many creative voices as I could in high-end furniture in a very authentic way,” she tells Introspective by Zoom from her home in London. “What really appeals to me is bringing these amazing stories to the fore using design as a tool to educate people about these communities.”

Muchiri launched SoShiro in London in September 2020 to showcase her inventive new design collections and host art exhibitions. The idea for the atelier-cum-gallery, located in a five-story Georgian townhouse in Marylebone, grew out of Muchiri’s early fascination with interior architecture and her desire to design living spaces that responded to different cultural needs.

Growing up in a former British colony, Muchiri was frequently perplexed to encounter houses imported straight from London with no consideration for the locale. In Kenya, the kitchen is central to the culture, and hours are devoted to food preparation, cooking and entertaining, but she’d see women crammed into one tiny room. “I knew I wanted to work with how spaces interact with people,” she says.

While studying interior architecture in Milan, she was struck by the Italian sensitivity to texture, beauty and balance, which would later underpin her designs. She completed a masters in design at the University for the Creative Arts in Farnham and founded an interior architecture practice in London in 2000.

But Muchiri found the “Eurocentric color palette” of high-end design at the time too restrictive — “I felt the design consumer could do with more variety” — and decided to create her own collections centered on cultural hybridity. She began with Kenyan crafts to avoid cultural misappropriation.

She had never given much thought to the beaded artifacts sold in tourist shops at home, but she became captivated by the work done by the Pokot women in northwest Kenya, who adorn everything from baby bottles to intricate, plate-like necklaces with bright beads. Traveling there, she learned that the necklaces were important indicators of status.

“They’re very uncomfortable to wear, but sometimes the women sleep with these necklaces on because of the identity it gives them,” she says. Muchiri’s first collection, Pok, was inspired by the Pokot women’s creativity and resourcefulness, although she commissions another Kenyan community known for its workmanship to do the beading.

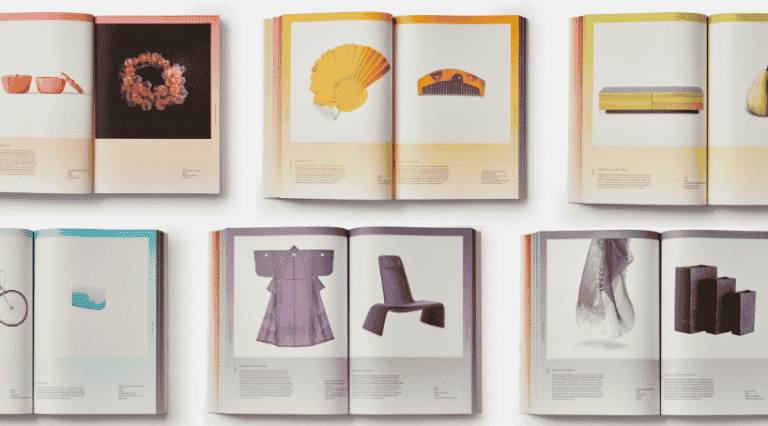

The undoubted showstopper of the collection is an Italian-made marble-topped, gray-oak-veneered credenza featuring exquisite handcrafted beadwork in eye-catching patterns down three central nubuck leather panels. The piece blends elegant classic lines with a dash of flamboyance, the tactile simplicity of its exterior concealing a generous storage system within.

When Muchiri brought the beaded leather panels to Italy and the finished unit to the Kenyan beaders, both communities were amazed. “There was this communication through creativity and art forms that was really exciting,” she says. The credenza remains one of Muchiri’s favorite pieces. “If it didn’t succeed, it would have been very difficult to continue, so it will always be a symbol of this journey for me.”

Other highlights from the collection include a luxurious baby camel wool throw, bedspread and cape ornamented with the circular bead design of Pokot necklaces; delightful pyramidal wooden salt and pepper grinders embedded with beads; and a handsome side table and stool of solid oak inset with polished marble balls, with pleasingly chunky legs and graceful curved edges.

Muchiri next turned her attention to a small community of Ainu sculptors in Hokkaido, the northernmost island prefecture of Japan, who were keeping alive centuries-old artisanal traditions, such as a fish-scale-carving technique practiced by only around eight craftspeople today.

She proposed a collaboration with Toru Kaizawa, a renowned Ainu artisan who made a piece in 2018 for the British Museum. The resulting collection, named Ainu, is a tour de force, marrying Ainu design with quality ceramics from a family workshop in Italy’s Veneto region. Its striking signature motif, created by Toru’s brother Mamoru, is based on the Blakiston fish owl, which the Ainu believe protects their culture.

Muchiri has created an impressive range of household items using this motif, from a stylish ceramic tea service to the magnificent HERBAL WARDROBE CART, a vertical garden on wheels with undulating hand-finished ceramic troughs to hold aromatic potted plants. Designing this piece so that functionality was not compromised was a challenge. “It was hit and miss. I almost gave up, but the result is fantastic,” she says.

The collection includes non-ceramic items, like the dramatic Blakiston Fish Owl lamp in polished metal and glass and the stunning gray steel and red lacquer All Aid wellness cabinet, with six color-coded drawers and a carved oak handle. Muchiri worked with the Kaizawa brothers to find the right wood for the cabinet, since the Ainu have a sacred relationship to forests and nature.

“I liked the protective nature of the owl,” she says. “It protects their culture, and this medicine cabinet also protects your health.”

Muchiri has grand ambitions to host cross-cultural events at her London space to complement her holistic approach to design. Because of the covid pandemic, she had to cancel a planned Ainu poetry reading for the collection’s launch, but she went ahead with an Ainu sake tasting, conducted by a sake sommelier, accompanied by Ainu eats. “We not only wanted people to know about the art form in terms of the furniture but also to learn about sake, the food, the language, the poetry.” she explains.

Last year, Muchiri unveiled her third collection, Layers, a collaboration with Alexandre Arrechea, a founding member of the acclaimed Havana art collective Los Carpinteros who has a thriving solo practice. In October, she staged a two-part exhibition of Arrechea’s artworks at the gallery alongside his furniture designs, like the distinctive pearwood and aluminum I Do desk, whose base spells out “I do” in retro red, digitally inspired lettering; and the superb double-sided pearwood Collector cabinet, decorated with a huge mosaic eye that forms a drop-down shelf.

For SoShiro, an events-based gallery dependent on its luxury products’ being physically experienced, the pandemic’s impact has been “like being hit by a freight train,” says Muchiri, noting that Brexit compounded the difficulties. What’s kept her going is “knowing what we were doing would be needed more after this.”

She says she is interested in artists “who are using their talent to speak about issues within the community and about global issues.” Through March 4, SoShiro is hosting an exhibition of paintings and a textile installation by the emerging South African artist Lulama Wolf, who explores Black spirituality in her work, often employing patterns and smearing and scraping techniques traditionally used by African women to decorate their homes.

Muchiri is planning a pop-up presence at the upcoming Milan Design Week and is working on the launch of a new collection. “We have up to ten collections penciled out with different communities around the world. We just haven’t been able to activate them because of the restrictions on travel and meeting, but the resources we have are huge,” she says.

Muchiri is also hoping to reach out to the design community to involve diverse creative voices in high-end real estate projects. “I want to be able to be the conduit for that,” she says. “Inclusivity has a richness — it makes us patrons of human heritage. You can live in luxury, but for me, pure luxury is how much impact you can have.”