March 30, 2015Iranian-born artist Hadieh Shafie’s first New York solo show is now on display at Leila Heller Gallery through April 11. Top: Detail of Shafie’s 9 Colors (Ketab Series), 2015. Portrait by Jason Fagan, all photos courtesy of the artist and Leila Heller Gallery

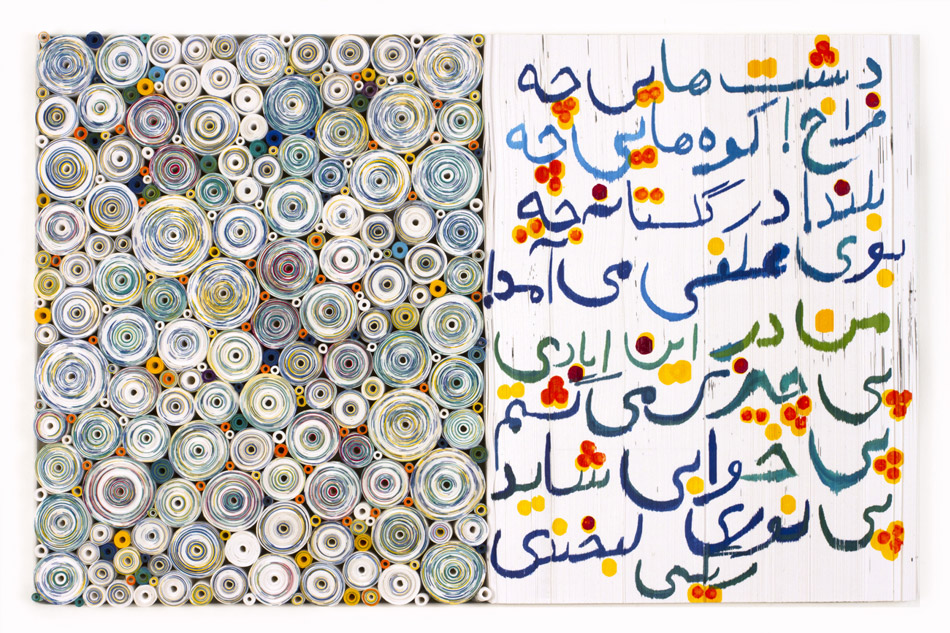

The Iranian-born artist Hadieh Shafie is standing in the middle of the Leila Heller Gallery, site of her first-ever New York solo show, explaining how she creates her paintings. Describing them as “part sculpture, part drawing, part artist’s book,” she says that most begin with numerous rolls of coiled-up paper strips, whose edges are saturated with jewel-toned paint. Turned on their sides and packed tightly into wooden casings, the coils mass together into swarming arrangements of variously sized circles and seem to pulse with suppressed energy, as if they are about to burst out of their frames.

“It is beauty that allows the viewer to be pulled in,” Shafie says, and indeed, her works are marked by vibrant, seductive color and formal power. But there’s far more to them than initially meets the eye: Upon closer inspection, one sees that each strip of paper is covered with Arabic lettering — although most of it is hidden deep inside the coils, as though the work were suppressing something else.

“I think about them as a library,” says the artist, whose interest in text was partly inspired by childhood memories of censored books and magazines in the days after Iran’s 1979 revolution. “They’re miniature books that go back to the most basic book form, a scroll.”

Over the last few years, Shafie, who is 45, has built a substantial reputation by producing increasingly complex variations on this theme. Although she has lived in America since the age of 14 and was trained in American art schools (she has two MFAs, from Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute and the University of Maryland, Baltimore County), she is usually regarded as an artist of the Iranian diaspora. In 2011, she was shortlisted for the Victoria & Albert Museum’s prestigious biennial Jameel Prize, awarded to a contemporary artist or designer whose work is inspired by Islamic tradition. Her work has been collected by patrons like Saudi Arabia’s Jameel family, who endowed the eponymous V&A prize, and the financier and author Saeb Eigner, and it has been acquired by more than ten museums, from London’s British Museum to the Salsali Private Museum in Dubai.

Despite her global renown, however, Shafie has not had a solo exhibition in New York until now. On view in Chelsea through April 11 are 16 paintings and one sculpture, all made within the last year. (An exhibition opening at New York University’s Abu Dhabi Center Gallery in New York on April 7 will feature her drawings.)

Taking a cue from Sol LeWitt and the other Minimalists Shafie revered in school, most of the work at Leila Heller begins with the same building block: a one-inch-by-11-inch strip of rag paper, cut from a standard letter-sized sheet. “It’s a paper size we’re all familiar with,” the artist says, adding that “it’s the standard size of a notebook.” Yet, in her hands, the strips seem less familiar. Printed and hand-lettered in Farsi, they are amassed by the thousands (or tens of thousands, in some cases) into hard-edged, mostly geometric shapes — circles, squares, rectangles and the occasional teardrop. Drenched in luscious colors, which range from primrose to purple, they produce alluring optical effects and call to mind fields of hypnotic flowers.

“My main influence, whether I like it or not, is a western way of thinking about art: For me, it’s very natural to put text on a grid.”

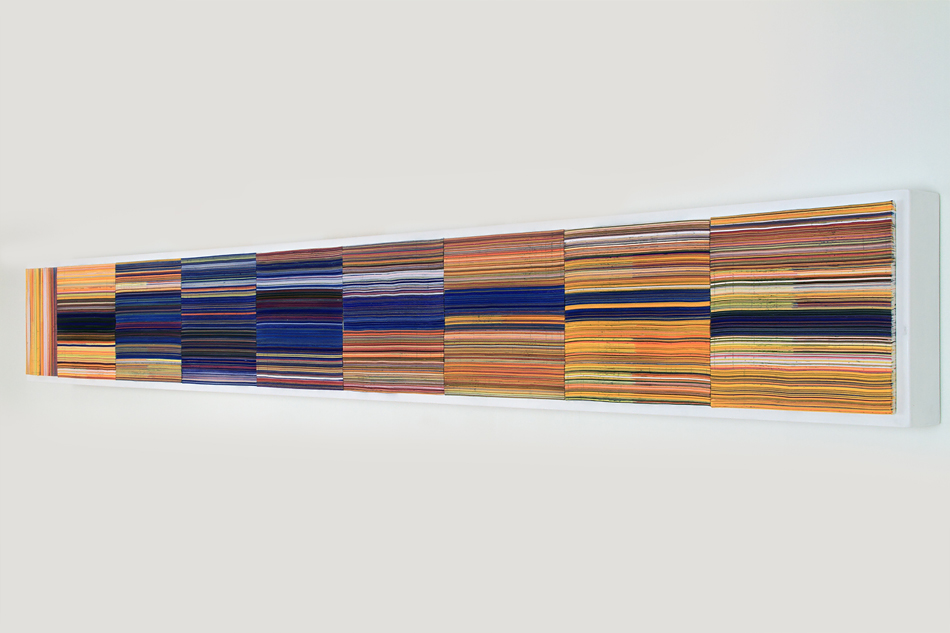

In Forugh 5, 2015, stacked strips of paper form rectangles that have morphed and sagged somewhat over time — an effect Shafie says is part of the artistic experience: “It’s like a live drawing.”

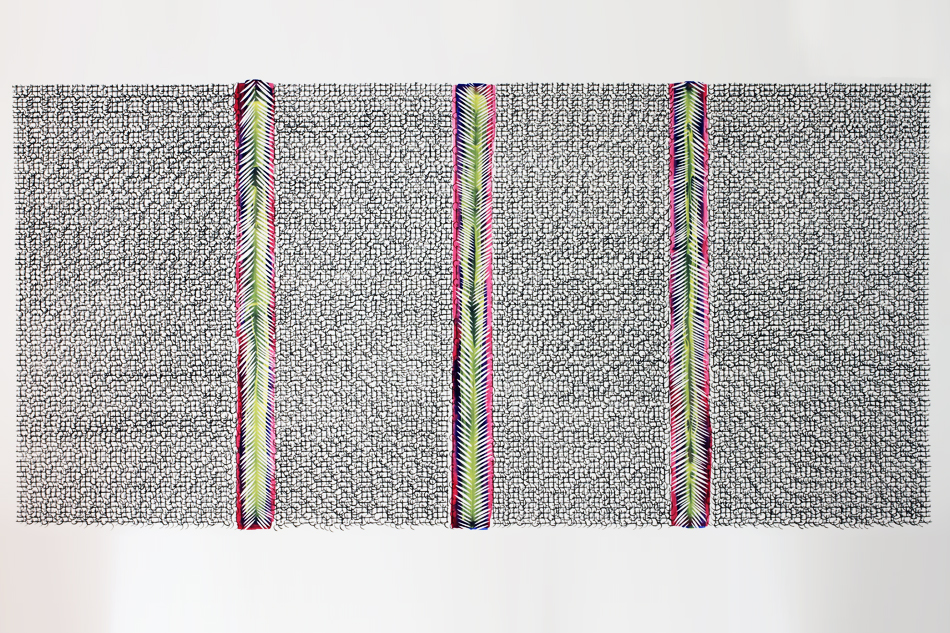

In many of her more recent works, she stacks the strips rather than coiling them, creating gently sagging rectangles. “Once they’ve lived in the work for a bit, they start to undulate,” Shafie says. “It’s like a live drawing.” Occasionally, handwritten lettering that often spells out “Eshgh,” the Persian word for “passion” or “love,” is marked across the work’s surface. Yet even for those who understand Farsi, the characters may be hard to read, because Shafie distorts them with a variety of systematized actions — pushing a stack into zigzags before lettering its edge or cutting and shuffling the strips like long, floppy decks of cards — creating loose scrawls that seem more reminiscent of Twombly or Basquiat than of the formalized curlicues of Persian calligraphy.

It’s Shafie’s blend of Western conceptualism and Islamic tradition that drew gallerist Leila Heller to the artist’s work when she saw it in a collector’s home in 2011, a few months before the artist was shortlisted for the Jameel Prize. “Hadieh didn’t look like a Middle Eastern artist,” Heller says. “She uses a very global language. I think that’s due to the fact that her education and upbringing was in Maryland,” where Shafie’s family settled after leaving Tehran in 1983. In fact, the artist didn’t become curious about Iranian modernism or tradition until she was in graduate school. “If you look at her work, she’s doing the reverse of what other Middle Eastern artists do,” Heller adds, by starting with an American artistic language — which includes Minimalism, Conceptualism and Color Field painting — and bending that to incorporate her own casual, unschooled twist on Islamic calligraphy.

When viewing Spike 8, 2015, from the side, viewers can understand the amount of painstaking labor involved in coloring and then coiling each one-inch-by-11-inch strip of paper.

This unusual approach also appeals to Maryam Ekhtiar, associate curator of Islamic art at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 2013, the museum acquired Shafie’s Abi Abi, 2013, a circular composition in hues of blue that seem to shift and deepen, depending on the light and one’s point of view. “The work is so enigmatic,” Ekhtiar says. “It looks different from different angles and in different lights, and the technique is not revealed until you get very close to it.” The shapes seem talismanic, akin to the Bedouin, Turkmen and Moroccan jewelry Shafie loves to wear, and the paper she uses to create them often suggest textiles, especially wax-resist ikat prints. Adds Ekhtiar: “Although Hadie’s work deals with the word, it deals with it in a way that sometimes you don’t even see it.”

To other curators, however, like Linda Komaroff, head of the art of the Middle East department at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, which also acquired a work of Shafie’s last year, the artist’s use of text is primary. “It’s such an important element in Islamic art,” Komaroff says. “Some artists, especially those who came to America at an early age, can be whatever the visual equivalent of bilingual is.” That said, she adds, when an artist chooses to incorporate text in the work, it’s “a way of making themselves distinct from the West.”

Shafie, for her part, maintains that she has taken pains to distance herself somewhat from Islamic tradition. “My main influence, whether I like it or not,” she says, “is a Western way of thinking about art: For me, it’s very natural to put text on a grid.” Her use of Farsi may introduce undulations into that grid, but she has also made a deliberate effort to use handwriting, rather than calligraphy, so that her text remains spontaneous and untrained. Incorporating her heritage this way is “a feminist thing for me,” Shafie says. “By doing that, I am asserting my person. I’m asserting that my mark is important, that it has something to say.”

“She uses a very global language,” dealer Heller says of Shafie, whose work incorporates elements drawn both from American artistic styles (Minimalism, Conceptualism) and from Iranian culture (Farsi characters and words).