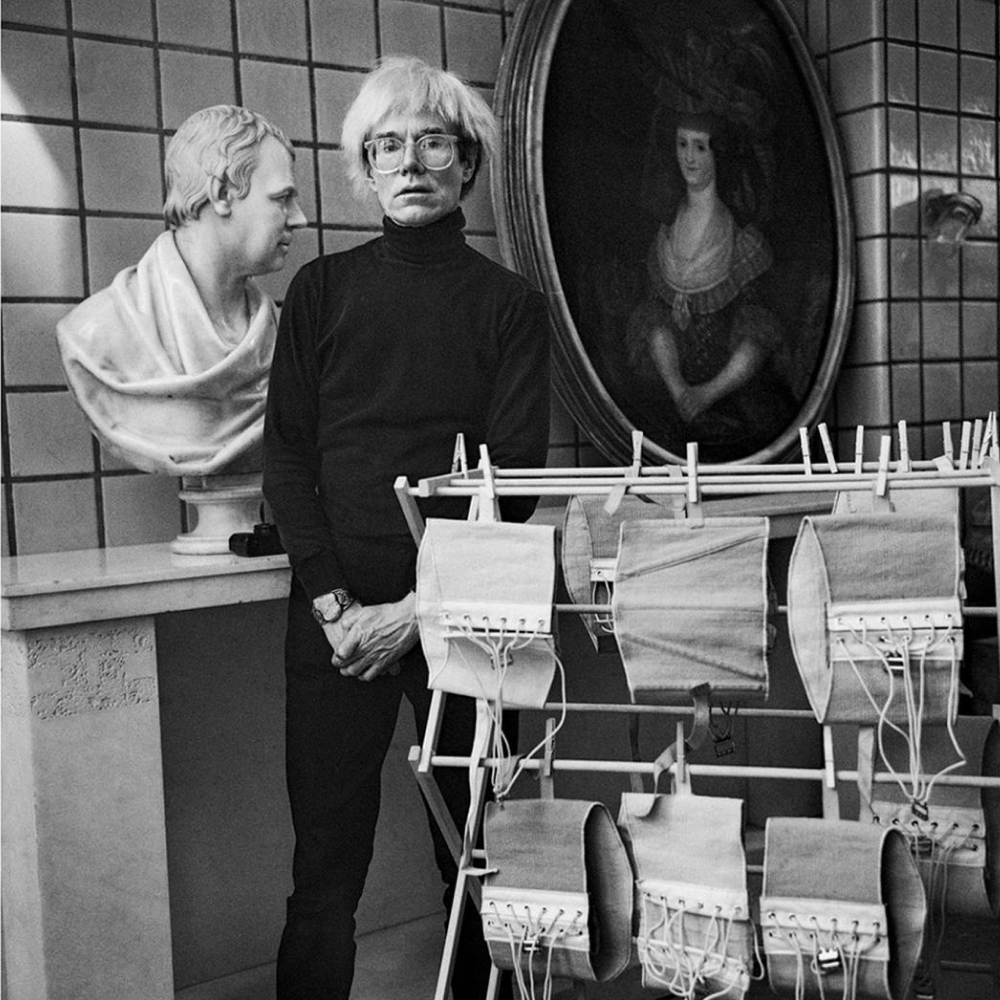

June 5, 2017An Irving Penn retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art highlights the photographer’s famous work in fashion and portraiture, as well as his lesser-known efforts, like his series of nudes and tradespeople (portrait, Irving Penn, New York, 1963, by Bert Stern). Top: Detail of After-Dinner Games, New York, 1947 (Photo © Condé Nast). All photos © The Irving Penn Foundation, unless otherwise noted

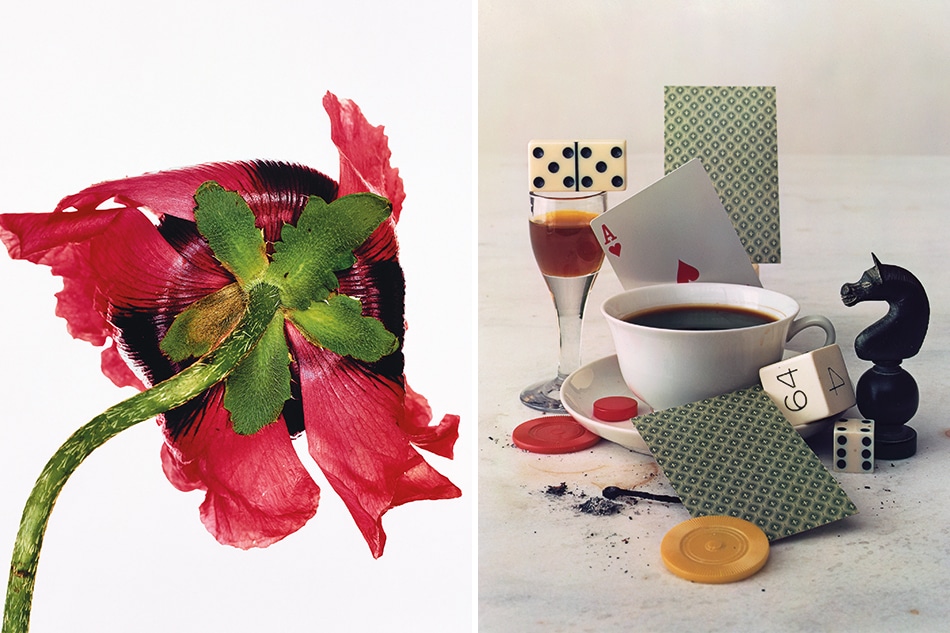

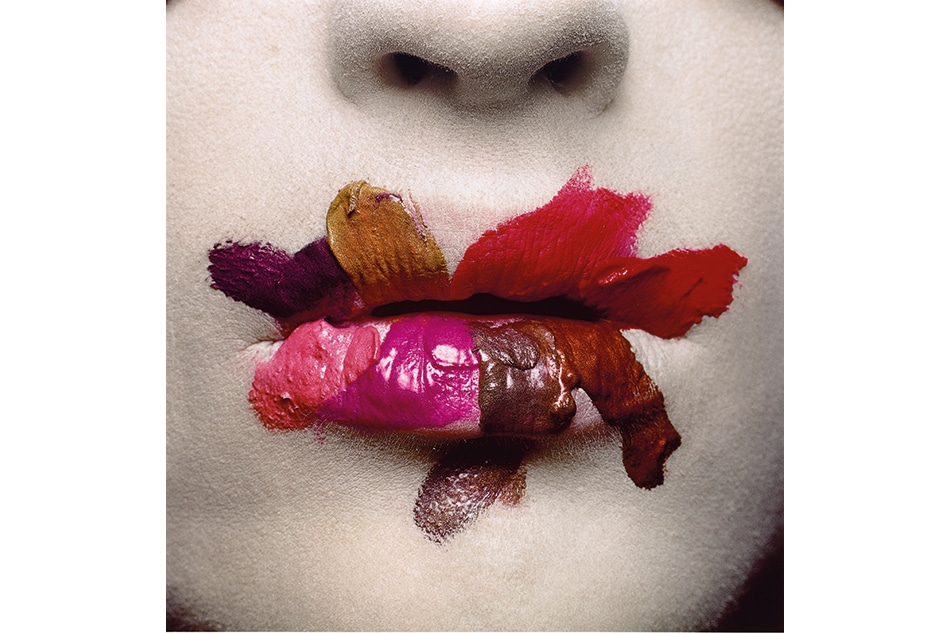

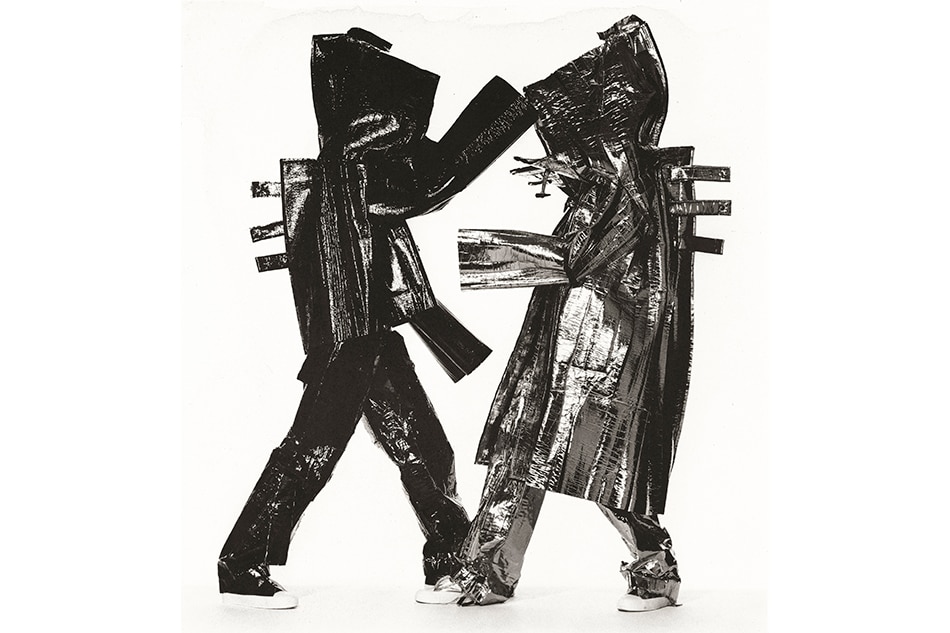

With a career in magazines that spanned the mid-20th century heyday of print journalism and lasted through the first decade of the 21st, Irving Penn was the preeminent photographer for six decades at Vogue, where he worked right up until his death, in 2009, at age 92. His refined and dynamic images of models, celebrities and products like Clinique and Jell-O pudding, all shot in compositions of stunning equipoise in the cool remove of his minimal studio setups, were designed to stop traffic and cut through the clutter of magazine pages.

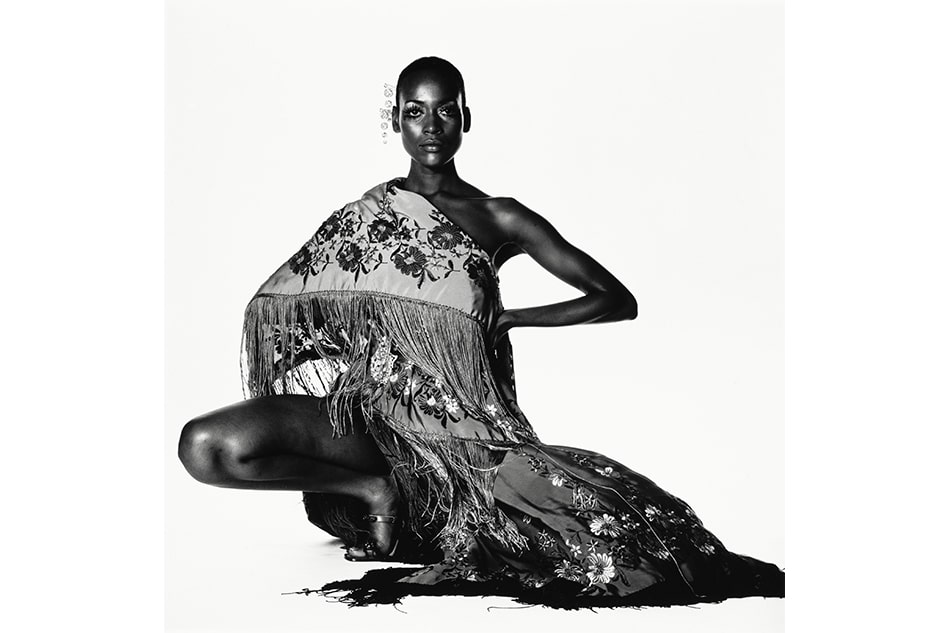

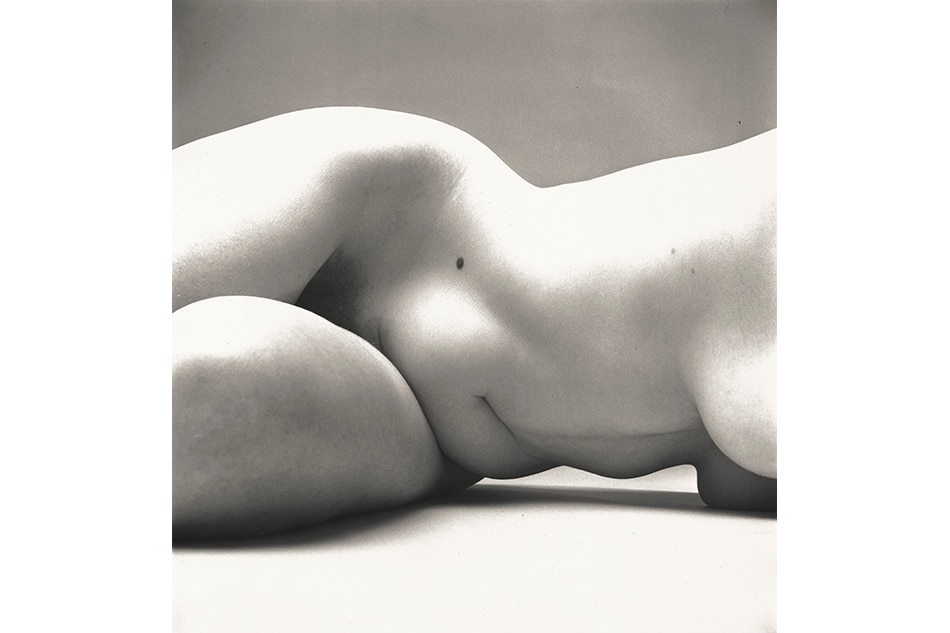

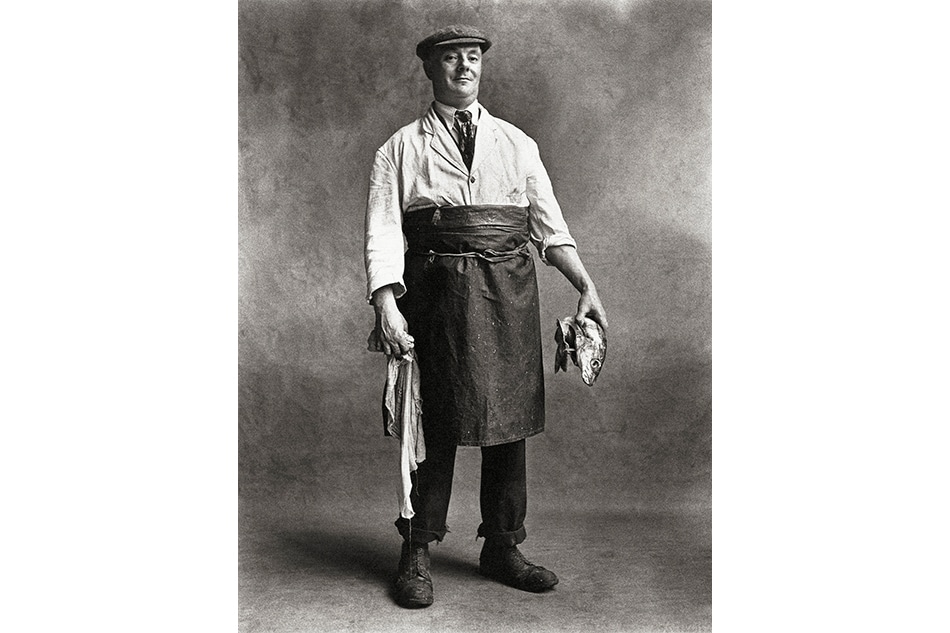

“Penn trained in the idiom of magazine imagery and mastered it, transforming fashion photography and defining so many things that we now take for granted,” says Jeff Rosenheim, curator in charge of photography at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. With the independent curator Maria Morris Hambourg, Rosenheim has co-organized “Irving Penn: Centennial,” the most comprehensive retrospective of the artist to date, comprising more than 200 photographs, many from a promised gift to the Met by The Irving Penn Foundation. “There’s a push and pull between his broad achievement and how he explored a single subject in depth,” says Rosenheim. Up through July 30, the show punctuates Penn’s well-known fashion shots, portraits and still lifes with discrete galleries devoted to his series on the Quechua (1948), his fleshy nudes (1949), his tradespeople (1950–51) and his monumentalized cigarette butts (1972).

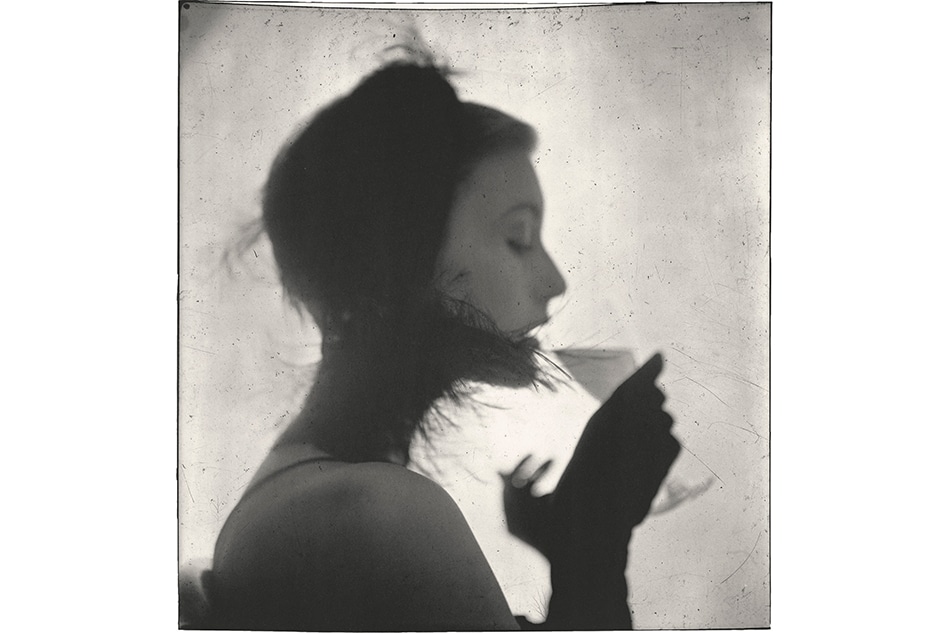

Truman Capote, New York, 1948

Penn flourished under the mentorship of two legendary art directors: Harper’s Bazaar‘s Alexey Brodovitch and Vogue‘s Alexander Liberman, both Russian émigrés like Penn’s father. Brodovitch introduced Penn to surrealism and avant-garde photography as his teacher at the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art and hired him as his assistant at Harper’s Bazaar during the summers of 1937 and ’38. Penn bought his first camera after graduating that year. He met Liberman in 1941, passing off to the recent New York transplant his freelance art director job at Saks Fifth Avenue. Liberman returned the favor by hiring Penn at Vogue in 1943 to sketch cover concepts, later encouraging him to shoot his unconventional juxtapositions of accessories and household items himself.

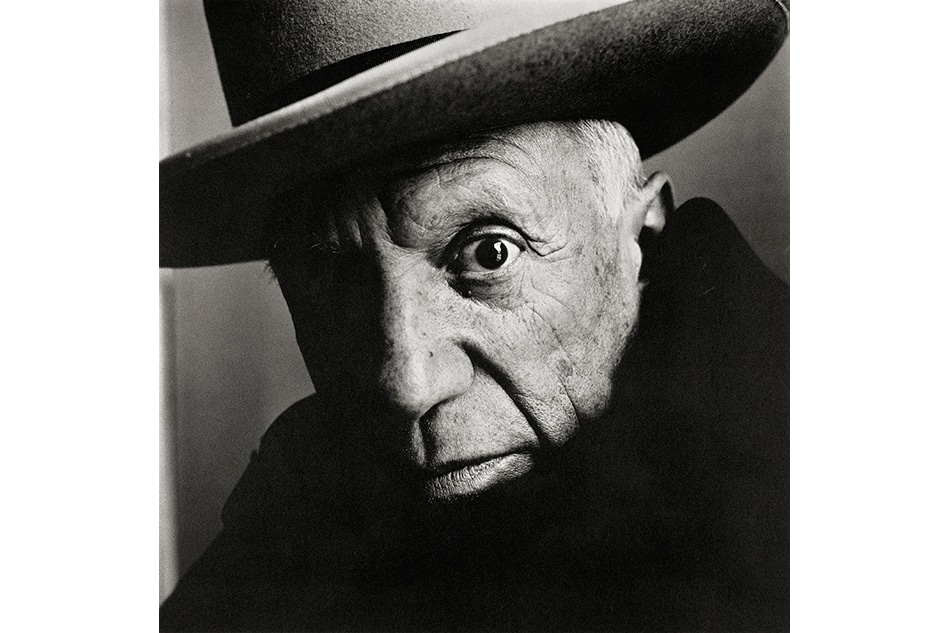

Assigned to photograph some portraits in the mid-1940s, Penn took a cue from the stage-set windows at Saks. He angled two studio flats in his studio and placed his subjects, including Truman Capote, Jerome Robbins and Salvador Dalí, in the resulting tight corner, literally and psychologically. Spencer Tracy leans jauntily against the walls in his portrait, while Georgia O’Keeffe simmers straight-armed in her confinement. “We can feel the pressure of the space,” Rosenheim says. “These corner portraits hold the light and push the personality of the subject forward.”

Penn didn’t work well with the distractions of the outside world. In 1950, when he was instructed by Liberman to buy an evening jacket and shoot the couture shows in Paris, he managed the assignment by having the dresses brought to him. He rented a top-floor studio with great light but no electricity and photographed models, including Lisa Fonssagrives (whom he married shortly after), against a mottled gray theater curtain that he continued to use for the rest of his career. Between deliveries from Dior and Balenciaga, he began his personal project “Small Trades,” in which he had local Parisians — a knife grinder, a mailman, a cucumber seller — pose for him with tools of their trade against the same backdrop. (He extended the series in London and New York.)

Cigarette No. 37, New York, 1972

“On any given day on the studio floor, Penn was working on a still life for a commercial job, he was setting up for a fashion shoot, he was doing a portrait of some celebrity, and then he had the fishmonger with the fish coming up the stairs,” says Rosenheim. “He treated everything the same, and everything ultimately has this kind of still-life quality, even the people.”

While Penn made bold, reductive still lifes for advertising campaigns throughout his career, in 1972 he applied his sculptural understanding of form to the unlikeliest of subjects: cigarette butts he gathered from the streets. “A stubbed-out cigarette tells the character, it tells the nerves,” Penn once told an interviewer. In his lush, oversized platinum-palladium prints, he elevates the lowly castoffs to heroic objects worthy of archaeological scrutiny.

This independent project aligned with a shift in the status of photography. “In the late 1960s and 1970s, there was this burgeoning museum culture that supported photography,” Rosenheim says. The Museum of Modern Art showed Penn’s cigarette butts in 1975, and the Met exhibited another series of material salvaged from the street in 1977. At this time, Penn also began revisiting his earlier photographs, reprinting them at larger scale and with the more painterly quality achieved with the platinum-palladium process.

“He’s reinventing the medium for a new audience — the museumgoer, the collector, the connoisseur,” says Rosenheim. “He transformed those images, made for the magazine pages, into objects with the physicality of an old-master painting or a great watercolor.”