February 20, 2017Julian and Isabel Bannerman’s new book explores the fantastical gardens they have created in the U.K. and beyond (portrait by Andrew Montgomery). Top: At Woolbeding Gardens, in West Sussex, they designed the Chinese bridge (painted “a good yellow”) to maximize views across the lake (all photos © Isabel and Julian Bannerman and Dunstan Baker 2016).

Isabel and Julian Bannerman are highfliers in the upper echelons of English garden designers. Designated by the Prince of Wales as “worthy heirs of William Kent, one of the greatest and most creative of early eighteenth-century ‘designers’,” in his introduction to their new book, Landscape of Dreams (Pimpernel Press), this husband-and-wife team has been in the business of designing gardens and garden buildings (classical temples, rock-hewn tunnels and fanciful follies) since the early 1980s, when they were invited by a friend to help landscape a grotto at Leeds Castle and stayed on to build a wooden hermitage.

Word got around about their interest in ruins and grottoes (they became known as “the grotty people”), and at the suggestion of Lord Rothschild’s daughter, Beth, he invited them to get involved in remaking a ruined garden around a restored dairy at Waddesdon Manor. This led to a succession of commissions, including creating a temple grove at Highgrove (the prince’s country home), replete with arbors, a pair of classical wooden temples and a towering gunnera fountain; restoring a neglected and now ravishing Arts and Crafts garden at Asthall Manor, in Oxfordshire (one of the childhood homes of the legendary Mitford sisters); and designing the wildly inventive Collector Earl’s Garden at Arundel Castle. Possibly their best-known projects are their own two gardens: at Hanham Court, near Bristol, which they owned for 18 years; and at Trematon Castle, their current home in Cornwall.

The Bannermans are addicted to saving derelict houses and shattered gardens, and they admit to wanting to create gardens with a dreamy “left alone” quality but understand that garden design also needs to be practical. Their book takes readers on a photographic tour of 16 of their biggest and boldest projects. They cheerfully acknowledge in their epilogue that this “is only part of the story . . . photography is one thing, gardening another.” Nonetheless, the volume reveals their pervasive sense of drama and their total immersion in the worlds of architecture, literature and history — which colors but never gets in the way of their intuitive, lighthearted approach to garden making.

Introspective recently spoke with Julian Bannerman about the book and the particular magic behind the creation of these very special edens.

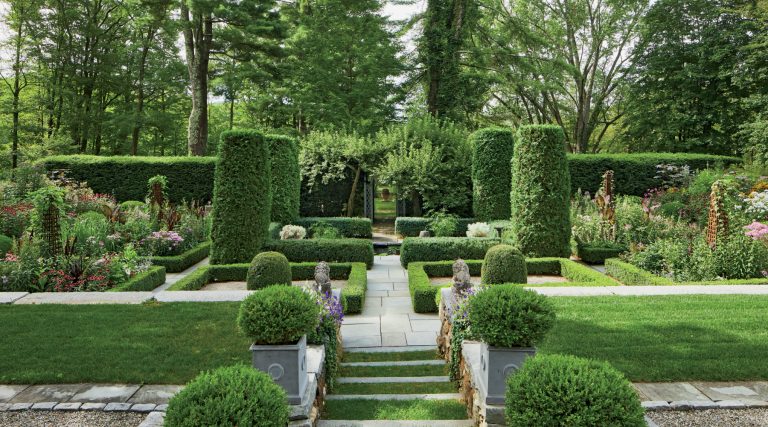

The Bannermans moved into Hanham Court in 1993 and lived there for 18 years, restoring the house and gardens. This view of the garden in winter shows frost-covered yew cylinders, yew balls, box balls, Euphorbia, frost-flattened Eryngium and the remains of a statue.

When you take on a project, do you and Isabel divvy up the terrain and assume different responsibilities?

No, we do everything together. The only difference between us is that I am more talkative.

How would you characterize your approach to garden design?

You know the expression “the genius of the place”? What’s most important for us is to get a sense of where we are. Garden design is about problem solving and the need to reconcile oneself with one’s surroundings. The fun lies in the problem solving. We want to make a good garden but not overdo it. Too often, garden design is like ordering Chinese food at a restaurant, where the tendency is to order too much food and too many different dishes.

Actually, we think about food a lot. This thing of eating outside is very English, so our gardens are very much for eating. It’s one of the reasons we make so many arbors: It rains a lot in England, but this means one can still eat in the garden. And even if it’s freezing cold by eight p.m., no one seems to mind.

Your book includes one project in the United States. How did that come about?

We received an invitation to enter a competition to come up with a design for the Queen Elizabeth II September 11th Memorial Garden, in New York City, on a small triangular plot at Hanover Square. Competitions are not something we normally do, but this was different. We plunged in and came up with a very simple design. You can see the plans in our book. However, there was a coup d’état, and it didn’t end up looking anything like what we had planned.

At Houghton Hall, which was built in the 1720s by Sir Robert Walpole, Great Britain’s first prime minister, the Bannermans updated the unfinished park. Leading to the antler temple, the vibrant border includes West Country lupines.

So many of your gardens, especially Arundel, revolve around fantastical buildings and structures. How do you find the craftsmen to carry out your often extremely complicated designs?

Over the years, this has become much easier, because if they are good, we work with the same people again and again. We love to work with people we know. Robert Kime [the noted interior designer, who is a good friend of the Bannermans] once said that work is all about networking and memory.

Explain your thinking about the public garden you created at Arundel Castle.

When we got this commission from the current Duke and Duchess of Norfolk, we were asked to think boldly. Inspiration came from an imagined historical garden made in the seventeenth century by the fourteenth Earl of Arundel at his London house and long since gone. The garden we made at Arundel had to be a dream and very theatrical. [It boasts pediments, temples, monumental doorways, obelisks and huge urn fountains.] The climax of the theatrical experience is a sixteenth-century water trick. [At Arundel, that refers to a “dancing crown,” which seems magically to spin and float atop a jet of water.] Arundel couldn’t be a “garden garden,” so it was an excuse to enjoy ourselves.

PURCHASE THIS BOOK

or support your local bookstore