September 4, 2017The go-to landscape architect for Palm Beach residents in the know, Jorge Sánchez has just released a book titled The Making of Three Gardens (Merrell Publishers). Top: An elaborate river-stone drive gives way to the upper garden of Carmona hedges, Bismarckia nobilis palms and Podocarpus hedges at the Turtle Bluff Estate, in Palm Beach. Both photos by Andre Baranowski

Jorge Sánchez, of SMI Landscape Architecture, is the mastermind behind many of Palm Beach’s most admired private gardens and public spaces, including the town’s famed shopping street, Worth Avenue, which he redesigned in 2010. Pictures of its iconic “living wall,” an 840-square-foot vertical showcase of textured, cascading foliage along the western side of the town’s Saks Fifth Avenue, have been Instagrammed around the world and cited by city planners as an archetype of imaginative design.

As a young boy in his native Cuba, Sánchez grew radishes in his family’s garden — and became hooked on horticulture. In 1959, the family moved to Florida, establishing a sugar business in both Palm Beach and Martin Counties where Jorge worked after studying business, finance and history at Villanova University. Eventually, interior designer friends asked the avid gardener and natural plantsman to help them plan their clients’ gardens, and before long, Sánchez’s hobby grew into a full-time job.

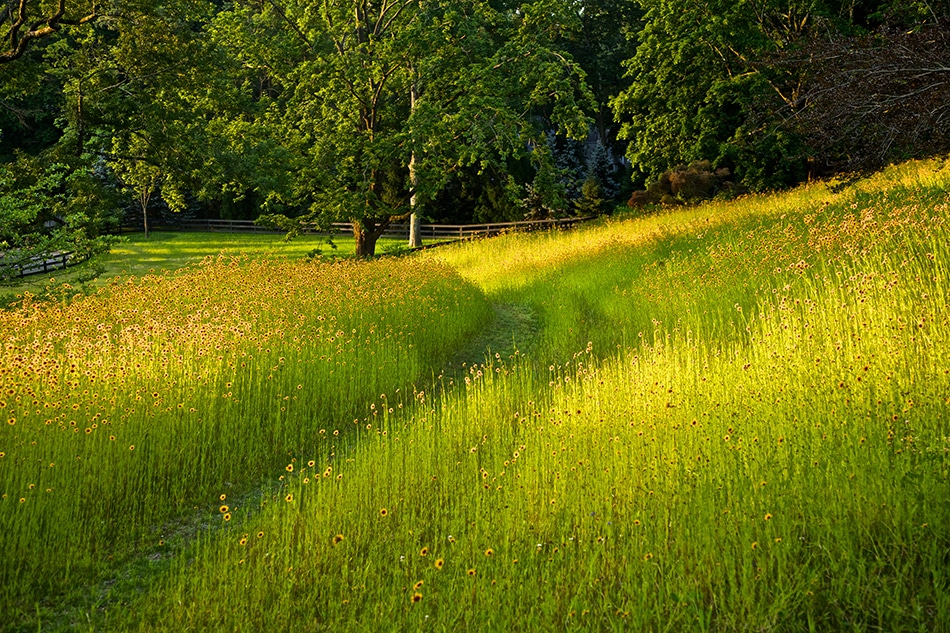

Sánchez, as courtly as he is creative, is loath to name clients, but he will concede that Facundo Bacardi, scion of the rum fortune, and investor Paul Tudor Jones, among others, have turned to him for their private residences. Public commissions include designing a classical fountain garden at the Gibbes Museum of Art, in Charleston, South Carolina, and Palm Beach’s four-acre Bradley Park, a lakefront green space, set to reopen to the public in November, whose restoration has been fully funded by the Palm Beach Preservation Foundation. But his most consuming project may be the ongoing transformation of a large swath of Florida scrubland in the far reaches of Port Saint Lucie County where, with the guidance of the Nature Conservancy, he and his wife, Serina, removed pines, chopped most of the underbrush and did controlled burns to create a family retreat whose vast grassy landscape includes stables, a five-acre spring-fed lake, a strategically placed sabal palm allée and a camellia and azalea garden, as well as groves of organic olive, mulberry, fig, pomegranate and apple trees.

‘New River’ bougainvilleas surround the spiral columns of the loggia at the Royce Estate, in Palm Beach. Photo by Steven Brooke

Sánchez spoke with Introspective on the eve of the publication of his book The Making of Three Gardens (Merrell Publishers), which details the evolution of a trio of glorious SMI projects: the Bacardi family property in Miami, which encompasses a sunken garden, grotto, bamboo forest and great oval lawn; a sprawling wild garden with fields and paths in Scarsdale, New York; and a dramatic two-tiered garden in Palm Beach influenced by the work of Beatrix Farrand, the celebrated 19th-century American landscape designer. The book also includes a foreword by the Duke of Devonshire, a longtime friend and devotee of Sánchez’s work. “Landscape gardening,” Sánchez states, “has allowed me to fulfill and enrich my life in ways I could have never imagined.”

Your first book, published in 2009, was titled The Civilized Jungle. Would you use that term to describe your gardening style?

I do prefer that the areas in proximity to the house are more formal and then become more jungle-like or woodsy farther from the residence. This progression lays the groundwork for asymmetrical symmetry, which I am fond of. As an example, I’m thinking of a particular garden where the plantings around the pool, including crinum lilies, are very symmetrical, yet the beds beyond include three foxtail palms and a plumeria tree on the right and two thinner palms of a different variety on the left. The rest of the planting is unbalanced. The entire composition has grace and does not feel forced.

Can you discuss garden design in relation to architecture and interior design?

I think of garden design as architecture. The first response to any garden ought to be the hardscape, or overall structure. This hardscape can be used in Long Island, New York, or in Phoenix, Arizona, as long as it is subservient to the primary structure on the property. Only then are plants that are appropriate for that climate zone added to complement the design.

What are some of the highlights of your career?

The majority of our work is residential, but we do accept commissions outside of that when they are interesting. Two that come to mind are Pan’s Garden [devoted to preserving Florida’s native plants, including gumbo-limbo trees, endangered Florida rosemary and butterfly orchids] and the redesign of Worth Avenue, which was the most challenging because it required unifying the east and the west ends of the street, which are very different, the east being of no note architecturally and the west consisting of cloistered walkways designed by Addison Mizner. Everybody had opinions on the design, including whether or not to bring back the coconut palms that had succumbed to a lethal yellowing blight in the 1970s. In the end, we put in the coconut palms.

Confederate jasmines and Ganges primroses frame a view of the coquina and river-stone terrace, which features a stone Bacchus, on the Shiverick Estate. Photo by Owen McGoldrick

As to private projects, I would have to say that developing my own ranch has been a treat. That was a transformation from cattle pastures and run-down woodlands to broad-stroke design — a large experimental form that has proved most rewarding.

Have you noticed trends, in terms of plant material, outdoor furniture, decorative objects and water features?

There are many, and that is what provides the spice to our work. There are also current realities that need to be accounted for, such as reductions in maintenance and conservation of water. Each client has his or her own likes and dislikes. Our mission is to interpret these wishes in the most aesthetically comprehensive way, while also creating gardens that are as pest free as possible, particularly the lawns. This is not an inexpensive undertaking, because so much of it is about amending the soil. We also look at maintenance and think about keeping down future expenses, which can influence, say, the number of annuals we plant.

How do you feel when you’ve finished a project?

It is always a mixture of satisfaction and disappointment that it’s over. Even though we try to keep close tabs on our finished projects, it always feels as if I’ve come to the end of something very enjoyable. A garden featured in the new book — Southlawn, in Scarsdale, New York — was one such project. Although, fortunately, our clients recently purchased an adjacent property, so there is more to come.

How does your new book differ from The Civilized Jungle?

The Making of Three Gardens differs greatly from our previous one. Aside from having very attractive images, the text is meant to be educational. It tells a prospective landscape gardener what the inner clues are that determine if one has the aptitude for this type of career. The book also describes how this trio of gardens came into being, from start to finish, with all the glories and the pitfalls.

PURCHASE THIS BOOK

support your local bookstore