December 5, 2016Last last month, London’s Design Museum opened its new home in a mid-1960s building reimagined by minimalist British architectural designer John Pawson. Above: The structure’s soaring main space is now cut through by a spiraling wooden staircase that also provides seating (photo by Gareth Gardner). Top: The building’s signature blue-tinted glass exterior and undulating roof. Photo by Gravity Road

On November 24, London’s Design Museum opened the doors of its elegant new home, a more than $100 million redesign of a 1960s icon on Kensington High Street, which it hopes will put it on a par with world-class cultural institutions and bring contemporary design into the mainstream.

The museum now occupies the former Commonwealth Institute, which until 2002 served as a miniature World’s Fair, promoting trade and cultural exchange among Britain’s former colonies. The new premises give the Design Museum 108,000 square feet of space, three times as much as its previous site, a converted banana warehouse on the southern bank of the River Thames.

“We thought the time was right to grow the museum, to take it beyond the exclusively design-orientated visitors that we’d had, to really make design part of a wider conversation,” says the museum’s longtime director, Deyan Sudjic. “So in some ways what Tate Modern did for contemporary art, we are hoping to do for contemporary design and architecture.”

Originally designed by architects Robert Matthew, Johnson-Marshall & Partners and completed in 1962, the square building resembles an aquamarine gem from the outside, clad with blue-tinted glass panels that reflect the parkland behind and topped by a wavy concrete and copper canopy roof. The distinctive exterior has been restored and rebuilt to preserve its original appearance. One crucial exception is that the cinderblock wall that used to back the glass facade has been stripped away to allow natural light inside.

The most conspicuous change is to the once dark and dreary interior, which has been revamped by British architectural designer John Pawson. In place of the raised marble dais that had marked a dead space in the building’s core, Pawson has created an airy oak-paneled atrium. The 100-foot-high roof, a curving expanse of concrete and exposed spoke-like girders, draws the eye upward for a stunning, sweeping view. “When you come in, the revelation is that you see this soaring space above you. People do go ‘Wow,’ ” Pawson says. “They do seem slightly moved, as it has a physical effect.”

Pawson wants museumgoers to come away saying, “That felt good, that looked good. I enjoyed going to this museum.” Photo ® Orla Connolly

Despite the “wow” factor, the building has an intimate feel, thanks to its manageable size and the warm oak finish Pawson used throughout. The museum is surprisingly tranquil, reflecting a similar atmosphere to that of buildings by Shiro Kuramata. Pawson spent time with the late Japanese designer in his studio decades ago, and has long admired him for his spare, sensual aesthetic. “I like clarity, and I like calmness,” Pawson says. “I think it’s unusual in a museum.”

At the center of the redesign is the idea of the museum as a place for education and social gathering. So a generous central oak staircase that leads to a mezzanine has cushioned steps for people to sit on — “a bit like a Greek outside theater,” notes Pawson.

Broad walkways spiral up and around the atrium, as in an open-pit mine, connecting the three floors. On the ground floor are the main gallery, the cafe and the gift shop; the second floor is given over mainly to a library, offices and the Swarovski Foundation–funded learning center, which contains a digital studio and a creative workshop; the top floor is divided among a display of the permanent collection, a restaurant, a members’ room, events space and four designer-residency studios. Two below-ground floors — new additions to the building — house a second gallery and a 200-seat auditorium.

Pawson’s scheme for the redesigned Commonwealth Institute changed very little from concept to execution. Artwork by John Pawson

Throughout the Design Museum, every detail has been carefully thought out, from the furniture for public spaces designed by Swiss company Vitra to the way-finding and signage systems by London firm Cartlidge Levene. “It’s a whole series of louder and softer moments. The new building acts as frame for the old one, so it turns itself into the exhibit, which gradually reveals itself in different ways as you walk around,” says Sudjic.

As for the exhibitions themselves, the museum has opened with several powerful design shows. On the top floor, a vibrant, free, permanent display titled “Designer, User, Maker” employs around 1,000 objects from the collection to examine the life cycle of a design from conception through manufacture to the consumer.

Pieces on view range from classics, like the Olivetti Valentine typewriter designed by Ettore Sottsass and the Sony TPS L2 Walkman, to Mikhail Kalashnikov’s AK47 rifle, a section of the first Model T Ford, a segment of the Pompidou Centre in Paris and a scale model of a new London tube train. Fashion is also represented, with a display of punk pieces by Vivienne Westwood and Christian Louboutin’s towering-heeled Pigalle pumps. Another highlight is the Crowdsourced Wall, featuring 200 everyday items from 25 countries that were chosen by the public, including a Bible, a Coca-Cola can, a football, a Burberry trench coat, a Nokia 1100 phone and an iMac.

“We thought the time was right to grow the museum,” says its director, Deyan Sudjic, “to really make design part of a wider conversation.” Photo by Gareth Gardner

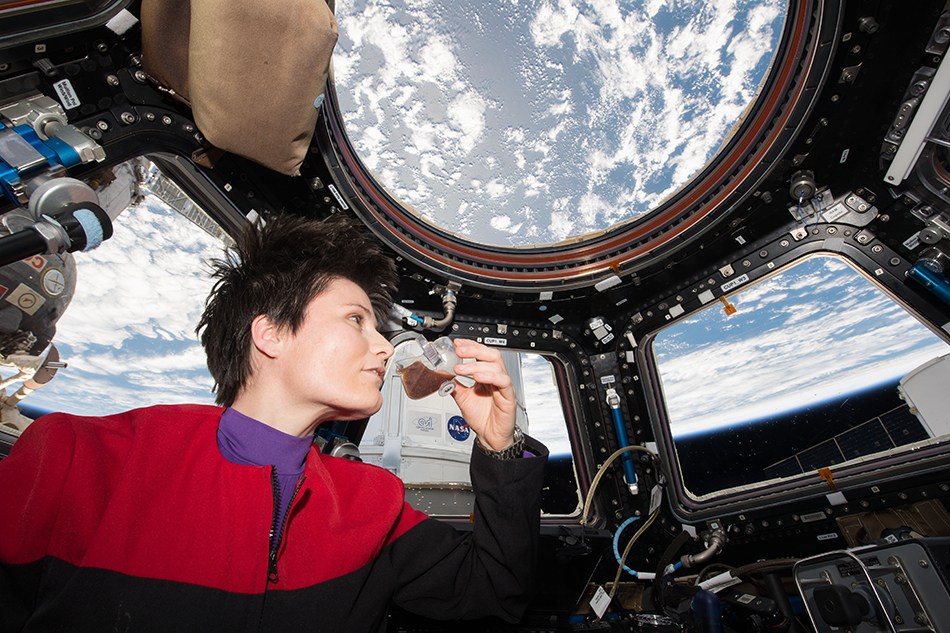

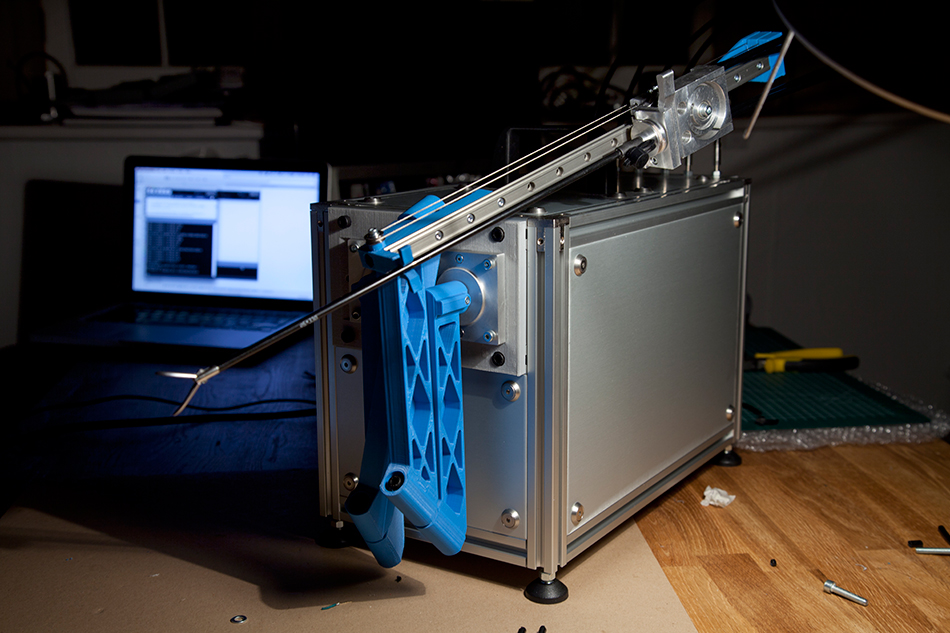

For “Fear and Love: Reactions to a Complex World,” a ticketed exhibition on the ground floor, chief curator Justin McGuirk commissioned a dozen architects and designers to create installations that respond to our anxieties about the world and how our lives are shaped by design. The third show is dedicated to the museum’s annual Designs of the Year awards, now in their ninth installment. Offering a snapshot of global design, this year’s contenders include such collaborative creations as a coffee cup for astronauts developed aboard the International Space Station, an open-source robot surgeon designed by students at the Royal College of Art and a drinkable book conceived by industrial designer Brian Gartside, graphic designer Aaron Stephenson and chemist Theresa Dankovich.

The breadth of the exhibition program demonstrates the expanded ambition and scale of the museum, which hopes to attract 650,000 visitors annually. When the museum was founded, in 1989, by British designer Terence Conran, the aim was to tell the story of contemporary design through a series of everyday objects. Today, it encompasses all aspects of design, including architecture, fashion and product and graphic design, as well as the issues surrounding them.

Conran has been supportive of the museum’s expansion from the start of the project, donating more than $20 million toward the new space. (The museum is a private foundation with charitable status and is largely self-sufficient, with limited public funding.)

Pawson, for whom this is his first major public project in Britain, says he is frequently asked whether he would have preferred to build something from scratch. The question bemuses him. “My business is not about leaving my mark. To me, I would almost have failed if people go round and say, ‘That’s Pawson, that’s Pawson.’ I want them to come away saying, ‘That felt good, that looked good. I enjoyed going to this museum.’ ”