August 15, 2016Italian-born, London-based designer Luciani Giubbilei’s new book, The Art of Making Gardens, delves into his time at the historic Great Dixter estate, in East Sussex, England, where he worked on an experimental garden plot. All photos by Andrew Montgomery, courtesy of Merrell Publishers

Luciano Giubbilei’s The Art of Making Gardens is not your typical book on the subject. Neither how-to nor coffee-table flower porn — although the photography, by Andrew Montgomery, is undeniably lush — the volume is a very personal account of a leading international landscape designer’s awakening to nature. The book makes the case for the inextricable link between aesthetics and botany.

“It’s a very pretentious title, I must say,” Giubbilei, 45, admits somewhat sheepishly. But in truth, it’s an accurate reflection of his considered approach to his practice. Indeed, the Italian-born, London-based designer speaks of trees and flowers, shrubs and grasses as if they were oil paints, marble or clay. Take his discussion of oak trees, one of his favorite elements: There is the texture of the bark, the way light falls through the leaves at various times of day, the sculptural quality of the trunk and branches — each of these elements finds a unique expression in every individual tree. “You have to choose the oak,” he says. No wonder designing a garden for a private client takes him three to five years and he limits his projects to no more than a dozen at a time. “Making a garden is one thing you can’t rush.”

Raised by his grandmother in Siena, Giubbilei found his calling while living in a rented house in the Tuscan countryside outside the city in the early 1990s. He was 20, studying to be a banker, with a part-time job making bread in an old bakery. It wasn’t that he had a sudden urge to dig in the dirt or that he was intoxicated with the romance of Tuscany. It was a far more primal need that first connected him to the earth: food. “I came to gardening through the love of growing vegetables and the love of moments you spend with friends and loved ones,” he says. “I grew the food, and I had a great passion for cooking.”

His affinity for the visual aspect of landscape design is connected to the same impulse — the desire to take care of people the way his grandmother had. “I remember we had a fig tree at the back of the house in Tuscany, and I’m thinking about where the table should go so the food is in the shade of the fig tree. The view was very beautiful. That’s where I started.”

Giubbilei says his time at Great Dixter has helped him understand that “a flower can look different because of the light, the time of day or the way it holds itself.” Seen here is the Anemone x hybrida, or “Queen Charlotte,” flower.

Planning to become a gardener, Giubbilei spent three months apprenticing with the gardener in charge of caring for the 18th-century gardens at Villa Gamberaia, in the hills outside Florence. “His name was Silvano and he was a very simple man,” Giubbilei says, “but he was very wise.” Noticing his young assistant’s interest in composition, the elder man urged him to study design at a college.

London provided the best options, so Giubbilei moved there and enrolled in the Inchbald School of Design, graduating in 1995. He was soon making flower arrangements for acclaimed chef Giorgio Locatelli and creating installations for others, including restaurateur and designer Terence Conran. In 1998, he landed his first residential commission. “It was a composition I had in mind when I left college — a simple terrace that spoke not just about gardens but about a harmonious composition of all the elements,” he says. The terrace, with a symmetrical arrangement of trees in the corners and carefully pruned, rounded shrubs in minimalist containers, all surrounding a sleek but comfortable seating area, was published internationally, sending more commissions Giubbilei’s way.

His early residential commissions were influenced by his youthful experiences in Italy. “I grew up in the center of Siena, where there is little of gardens,” he explains. “The gardens I saw as a kid were made of gravel and trees, geraniums on the windowsill. It was very simple.” He was concerned primarily with compositional space. “It was very architectural, very high-impact, almost theatrical. Siena has a very theatrical presence. You look through the alleys, the light is very dramatic. We obviously think it’s the most beautiful place in the world, Siena.”

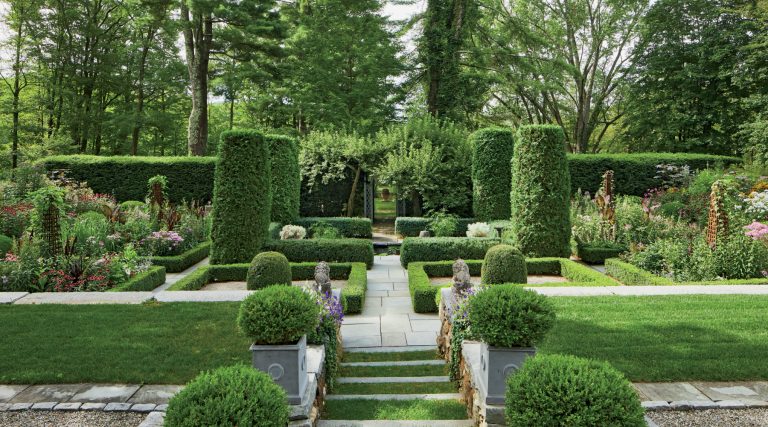

While sticking to a vocabulary of trees, bushes and grasses, along with stone, wood and contemporary sculpture, Giubbilei steadily built his reputation in Britain, the United States and Europe. And he won awards, all the while eschewing the flowers for which British gardens had been famous for generations. His gardens were sensitive studies in proportion, silhouette and light. They were green, with accents of brown. They were not about explosive color.

Parsnip flowers provide a pop of lime green in the gardens of Great Dixter, seen on a misty morning in early June.

Then, in 2009, Giubbilei was asked to design the Laurent-Perrier garden for the Royal Horticultural Society’s Chelsea Flower Show, the preeminent annual exhibition of its kind. The sponsor had one of Giubbilei’s serene, green spaces in mind. “I thought, ‘That doesn’t make sense,’ ” he says. It was the Chelsea Flower Show, after all. “Ultimately, you make a garden for the people who are going to see it,” he says. He wanted this one to have a sense of grandeur, to “make a great statement.” Giubbilei’s geometric hedges and floral borders won a gold medal.

He followed that two years later with a design for the show that included a bamboo pavilion by Japanese architect Kengo Kuma, abstract, pinkish stone sculptures by British artist Peter Randall-Page and a gentle waterfall. The flowers were subtle purples and pinks. “The colors, I wanted very quiet,” Giubbilei said at the time. “I always say I’m a quiet person, so I wanted that to reflect me.” He walked away with another gold medal.

But he was not completely happy. “I had a lot of doubts because, although I knew people would come and see how beautiful it was, it also touched my sense of integrity, in that I knew this would never work in a real garden,” he says. The gardeners who had assisted him were expert at forcing the flowers to bloom spectacularly for the five days in May when the show was on. It felt fake to Giubbilei. “There are tricks. You can’t see the tricks.”

Serendipitously, he met Sir Paul Smith, the British fashion designer, at the show. “He invited me to come to his studio to just have a chat,” Giubbilei recalls.” He’s a very open man, very generous. He’s very interested in gardens.” Giubbilei felt at a crossroads, both personally and professionally, and Smith gave him some sage advice. “He’s the one who said to me, ‘Maybe you should go and learn something new now. Maybe it’s a good time, in your forties, to learn something you could really use the rest of your life.’ ”

Fashion designer Paul Smith (right) says that he and Giubbilei share a bond in their constant curiosity.

To that end, Giubbilei visited Great Dixter, a historic garden in East Sussex that served as a lab of sorts for gardener and writer Christopher Lloyd throughout the latter half of the 20th century. Giubbilei had clearly mastered the design component of his field; now he was determined to delve into the horticultural part. “I wanted to understand more about flowers and growing plants,” he says. Great Dixter’s head gardener, Fergus Garrett, surprised him with an offer: Giubbilei could have his own flower bed on the estate where he would be free to experiment, cultivating whatever flowers he chose however he liked. Garrett, who became his mentor, told him, “There is no right or wrong about what you are doing here. You have to develop something that is yours.”

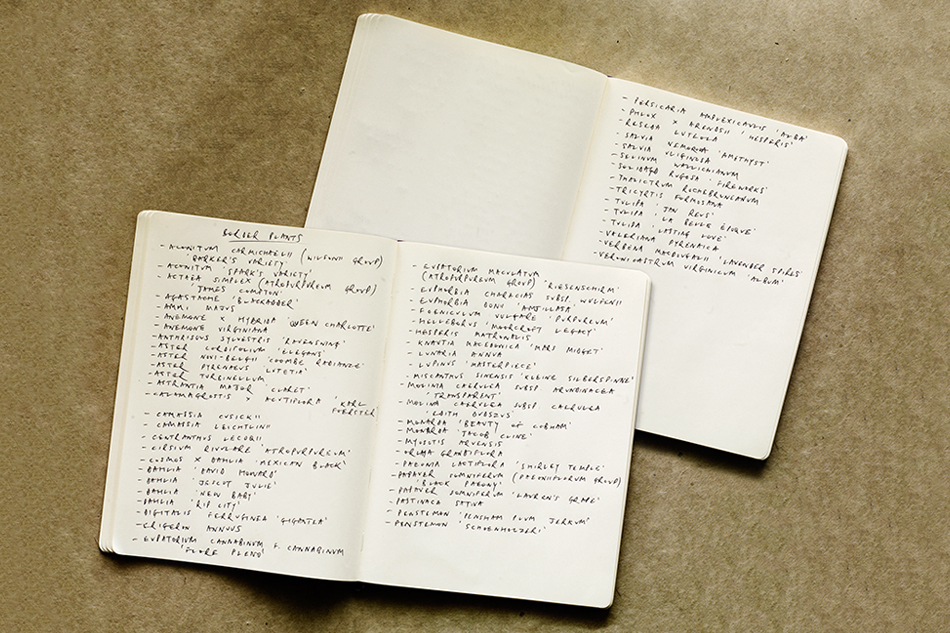

Since Giubbilei lives in London, a couple of hours away, and travels frequently for his business, Garrett assigned him an apprentice to look after his plot when he was away. Giubbilei planted tulips and dahlias, lupins and forget-me-nots. His piece of land was only 49 by 8 feet, but it became a haven of pink, purple, red, blue and green blooms, some tiny and delicate, others tall and textured.

At Great Dixter, Giubbilei found what he calls an “almost monastic environment,” where growing plants is almost a sacred endeavor. One of his most important revelations in his five years there was how much effort goes into creating what looks like a field of wildflowers. “I’ve always been very precise,” he says of his restrained designs. “English gardens, they are as precise as my perfect gardens. The idea that an English garden is wild — no.” Its beauty, he notes, comes not only from its palette but from “how this composition moves with the wind and the seasons.”

Giubbilei, working in his 49-by-8-foot plot at Great Dixter, says that plants don’t want to be placed too close together or too far apart.

Giubbilei also learned practical lessons about managing the change of season, how to prepare the soil and stand on boards so as not to compress it. He came to better understand the concept of plant spacing, or what he calls “plant companionship”— important not only aesthetically but to reduce weeds and to camouflage a gap if one specimen fails. “Plants like good company, like us,” he says. “They don’t like to be put too far apart, one from the other. They like to be put close.”

Perhaps most important, he came to accept that his chosen artistic media cannot always be manipulated or bent to his will. The second time he planted La Belle Epoque tulips, for instance, even though he used the exact same methods as he had the first time, the blooms were not as tall nor as deep a shade of pink. He asked Garrett what went wrong, and his mentor explained that the weather had been markedly drier and warmer than in the previous year. Gardening, Giubbilei says, is not like mixing colors of oil paint, easy to replicate. “This is nature.”

Two years ago, he returned to the Chelsea Flower Show, creating a garden displaying a subtle interplay between stone and tree bark, light and shadow, water and earth. He didn’t shy away from color, working with yellow, purple and pink flowers. This time he took not only a gold medal but Best in Show.

The Art of Making Gardens does not end there. It goes on to discuss some of Giubbilei’s other inspirations, from the minimalist sculpture of Isamu Noguchi to the exotic, glass- and mosaic-filled London studio of 19th-century artist Frederic Lord Leighton. It also takes the reader to yet another Giubbilei triumph: his collaboration with sculptor Ursula von Rydingsvard on an installation at last year’s Venice Biennale. In what has become a permanent intervention on the Venetian landscape, he created a winding gravel path through the Giardini della Marinaressa.

As for his little plot at Great Dixter, Gubbilei is still working it. “I took everything out,” he says. “I’m going to start again. I wanted, after the book, after five years of being there, to start fresh. Fergus told me, ‘If you have to stay here, you have to push yourself again.’ ”

PURCHASE THIS BOOK

or support your local bookstore