October 11, 2020Barry Malin did not take a conventional path to owning a gallery. Although he frequented the Albright-Knox Art Gallery as a child in Buffalo and took a lot of art history classes as an undergraduate at Williams College, Malin went on to become a plastic surgeon specializing in facial reconstruction for head and neck cancer sufferers.

He indulged his art interest as a collector, amassing some 1,500 works, with an emphasis on contemporary African art. After frequently counseling patients to make the best use of their limited time, Malin eventually took his own advice and switched careers.

In 2014, he opened a small gallery in Chelsea called Burning in Water (after verse by Charles Bukowski) focusing on work with sociopolitical relevance. Now relocated in a spacious split-level space on West 29th Street and with a new, simpler name, Malin Gallery boasts a growing and diverse roster. “Our artists all seem to be on the same page in terms of some of the bigger issues they want to address with their work,” says the dealer. “As time has gone on, that’s become less directed on my part and more just the character of the gallery.”

Here, Malin talks about his evolution as a gallerist and some of the artists he has championed.

How do you think your experience as a doctor informed your collecting and your approach as a dealer?

I worked with patients and families who were essentially facing the end of life. It was pretty grim. Art was something that buoyed me. It felt like this kind of spiritual lifeline. In the things I want to present at the gallery, there’s usually an element of gravitas.

The art world certainly exhibits growing interest in and awareness of artists who have been through the criminal justice system. But when you were just starting out in 2015 and you took on Jesse Krimes, who served a six-year prison sentence for drug possession, did it feel like a risk?

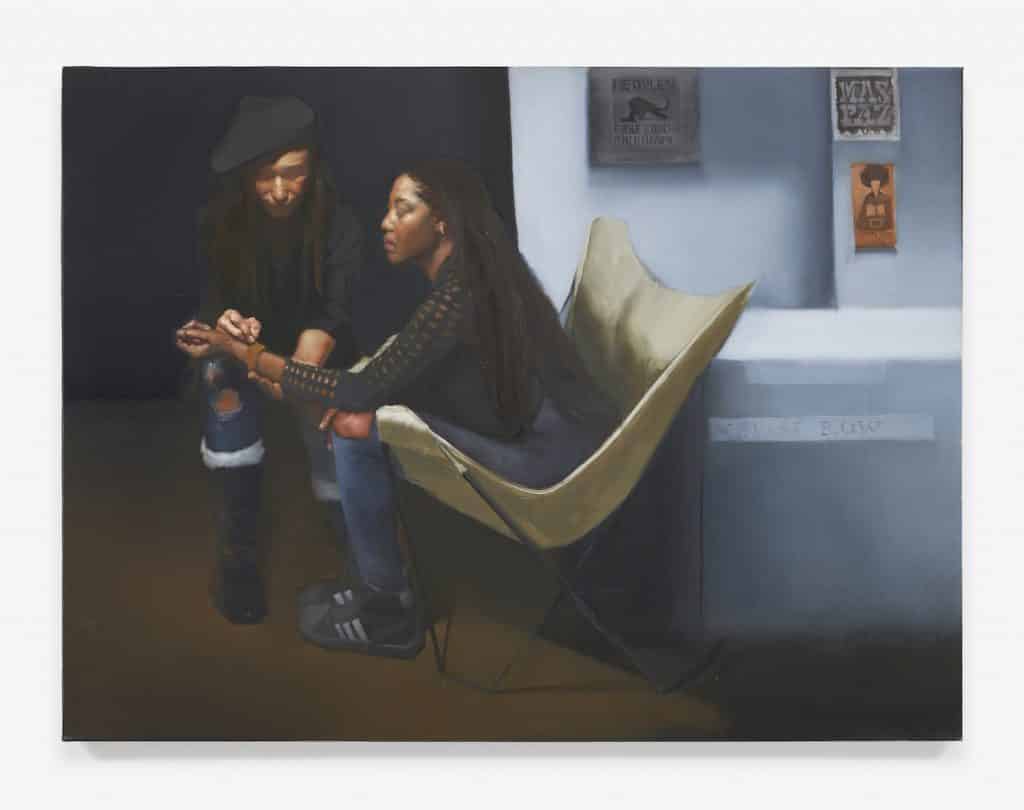

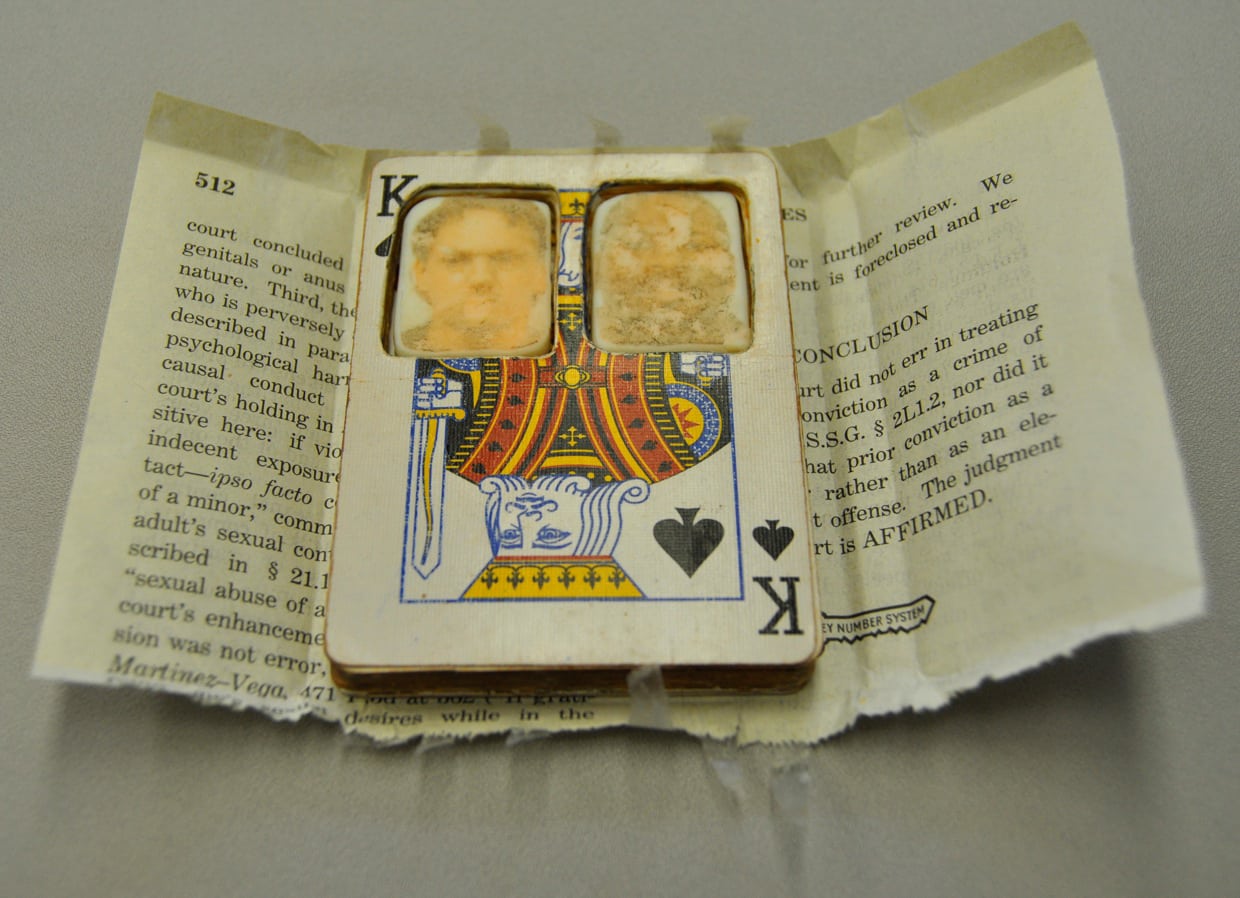

His work just seemed so urgent and relevant that we took a leap of faith. Jesse had been an artist before he went to prison. He started making these portraits using shards of prison-issued bars of soap. There are more than three hundred of them, almost one for each day he was in solitary. For his first exhibition, we built shelves floor to ceiling and showed all the soaps.

The whole goal for Jesse was to make the transition from being this guy in prison who made these crazy works with soap to being an accomplished fine artist who happened to have had this very important experience. We’ve consciously tried to shepherd him through that process.

After that first show, he was fortunate enough to be one of the first grant recipients in a program called Art for Justice that Agnes Gund started. She’s become a supporter of Jesse’s and now collects his works. We’re really gratified that his soap work titled Purgatory and his bed-sheet work are exhibited at MoMA PS1 this fall in a group show on mass incarceration.

Have you helped bring other artists new recognition?

We’ve been fortunate to have a role in the remarkable renaissance of Oliver Lee Jackson, an 85-year-old African American artist who blends figurative elements in abstract compositions. Oliver’s success was a long time coming, and there were other people involved, most notably Harry Cooper, the curator who organized his 2019 show at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. We followed that show with our big show of his paintings here. Those things worked together.

Are there works that you’re particularly proud of having placed in museum collections?

The Smithsonian acquired Oliver’s felt Triptych [2015] in the National Gallery show. We were a conduit, one of the parties involved in making that happen. We’re also in the process of working on a large-scale metal sculpture by Oliver that, if everything goes well, is going to be a permanent installation at the National Gallery.

With the Black Lives Matter movement, have you seen a greater interest in more socially oriented work?

Our current show of Sylvia Maier [“About Sangomas and Soothsayers and Mischief,” on view through November 1] — whose subject is her community in the Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn, which has a large population of people of Haitian descent — had been planned for a year but now has sort of met its moment. It’s not like we set out to do that, but we had the ingredients in place, so it wasn’t an accident either. Recent events have contributed to the commercial success of the show. We’ve been selling the work during what’s typically the slowest time of the year and in the middle of a pandemic.

What piece do you love too much to sell?

I have two very large-format photographs by Richard Mosse. The images are of child soldiers in the middle of the Congo, but everything is bright pink, including their uniforms. The subject matter and the way you perceive it on a sensory basis don’t fit, yet they fit perfectly.

What piece do you regret having sold?

Valerie Hegarty did a series of ceramic sculptures that were topiaries of George Washington. There was one where his sword was detumescent, and he was sad and weird looking. The piece hadn’t sold, so Valerie wanted to give me something and offered it to me. A few weeks later, someone wanted it. Of course, I was not going to deny her a sale, but that one hurt, because I really loved the piece.