August 15, 2021London’s Geffrye, a museum of domestic life occupying a complex of early-18th-century almshouses, has reopened after a three-year, $18 million expansion. Long a secret treasure, it is bound to be a secret no more. With its rebranding as the Museum of the Home, its purpose is now evident even to those not already “in the know.”

Exhibition space has doubled, and a collections study room and education facilities have been added. As before, the main floor presents a historical survey of British middle-class domestic interiors.

But, as Sonia Solicari — who has been the museum’s director since 2017 and has overseen its transformation — observes, the institution previously “lacked the experience of the home and its emotional aspects.”

The series of new lower galleries now tell contemporary stories of many different people in their British homes, including what life was like when home became the whole world during lockdown.

I fell in love with the Geffrye on my first visit, 20 years ago, and worried that enlargement might somehow spoil it. It has not. The chemistry between building and contents still makes for an experience that feels uniquely personal and, therefore, moving.

The 1704 will of Sir Robert Geffrye, a self-made success whose investments included a share in a slave-trade ship, directed that most of his fortune should be used to create and endow almshouses (homes for impoverished pensioners). And so it was.

These 14 interconnecting structures were home to as many as 50 men and women at a time for 200 years. Today, they appear as a single large and rangy dark brick house set on a vast green lawn. It is a charmer, its two side wings open wide in welcome.

“What makes a house a home?” is the unvoiced question asked by the present-day museum. The building answers: warmth, solidity, security. Once you’re inside, answers multiply.

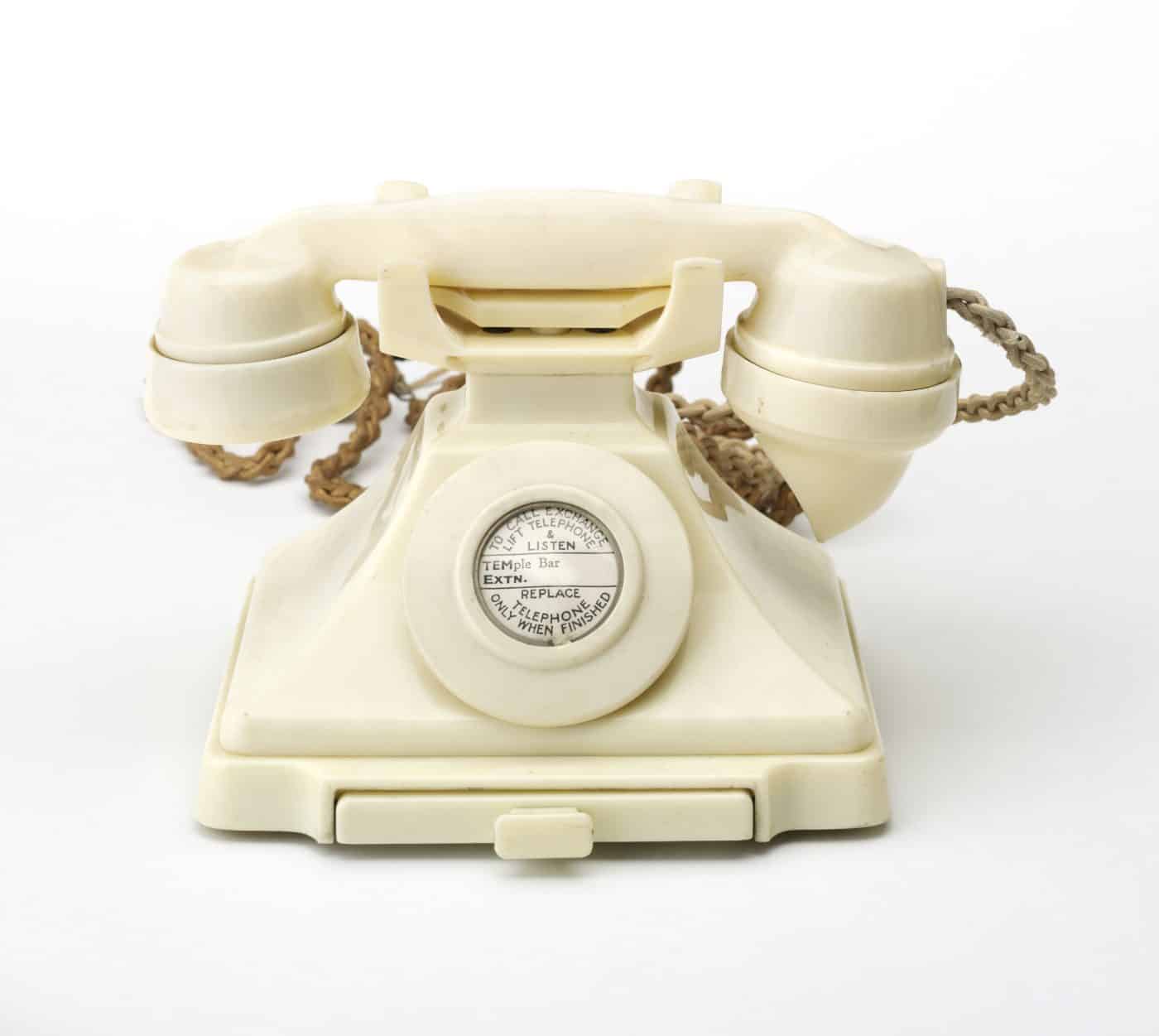

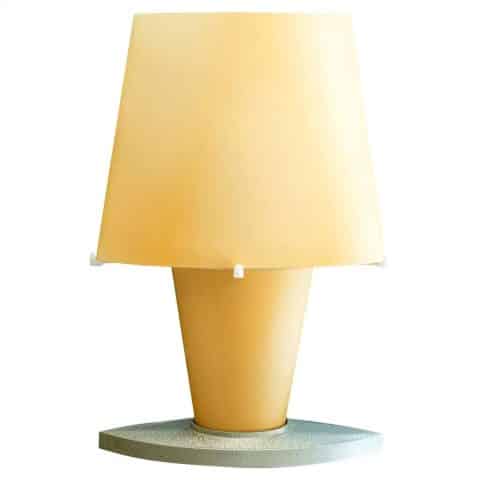

“Rooms through Time” presents a parade of 10 period rooms introduced by “Domestic Gamechangers,” a lively small display of products and inventions that have dramatically altered daily life since the almshouses were built, 300 years ago. Among these are electric light fixtures and clocks, a bright red rotary landline phone, an Amstrad home computer from the 1980s and Alexa chattering away about the weather.

A hall as it might have looked in 1630 is the first of the period displays. This begins the story of how the living room’s role has evolved over the centuries. Here, the austere dark wood table and surrounding chairs provide a place for meals, Bible readings and children’s games. The last of the rooms is multipurpose too: The 1998 “loft-style” space has a platform bedroom reached by a ladder; below, a counter separating an open area from the kitchen is both a place for breakfast and, as evening approaches, a bar.

In between the two, you’ll find an 1879 Victorian parlor and a 1976 Afro-Caribbean front room, as well as a 1745 Georgian parlor and drawing rooms from the Regency era and World War I, among other living spaces. These displays robustly express the conviction that you can’t have too much of a good thing — especially if it involves patterns.

The Victorian parlor has plush upholstery, heavy drapes and an upright piano. Every flat surface is covered: There’s a greenery-filled terrarium, a glass dome stuffed with stuffed birds and a cast of a thousand knickknacks. The colors are subdued — you sense that here, everyone whispered.

The equally maximalist Afro-Caribbean room, on the other hand, is a banquet of hot, spicy colors. Starched cotton crochet work, much of it orange, red or violet, rests on every surface, including the top of the TV. Sit on the sofa and lean against a pair of life-size crocheted cats.

In the cellar below — originally the almshouses’ kitchens, laundry and coal stores — are the sleek new “Home Galleries.” Here, the focus is on people. Their ideas about home are reflected in texts, photographs, videos, a soundscape, old prints and mini-displays of domestic objects, from teapots to textiles.

Photographer Mark Cowper’s contribution is a standout: A photomontage of 32 images, it surveys decorating taste in 2008. Each shot shows a different living room within the London high-rise where Cowper lived. They are identical in plan but vastly different in decor choices. (The only common denominator is a large television set.)

The downstairs galleries open directly onto the back of the house and a series of richly scented period gardens that complement and amplify the displays inside. They begin with clipped boxwood Tudor knots and end with a contribution from the revamp’s architects, Wright & Wright. The flat roof of the firm’s sleek, new one-story, open-plan study center is covered in Mediterranean plants — practicality (the garden insulates) and delight.

Nearby is the museum’s new entrance, which conveniently faces the Hoxton Station tube stop. But first-time visitors should go around to the front and enter as those who lived there did. It is magical, and it will make all the difference.