June 16, 2019Among the 300-odd top international dealers showing Old Master, Impressionist and modern paintings and assorted other treasures at March’s TEFAF Maastricht, in the Netherlands, the London-based Osborne Samuel Gallery stood out for the edgy boldness of its specialty: modern British art.

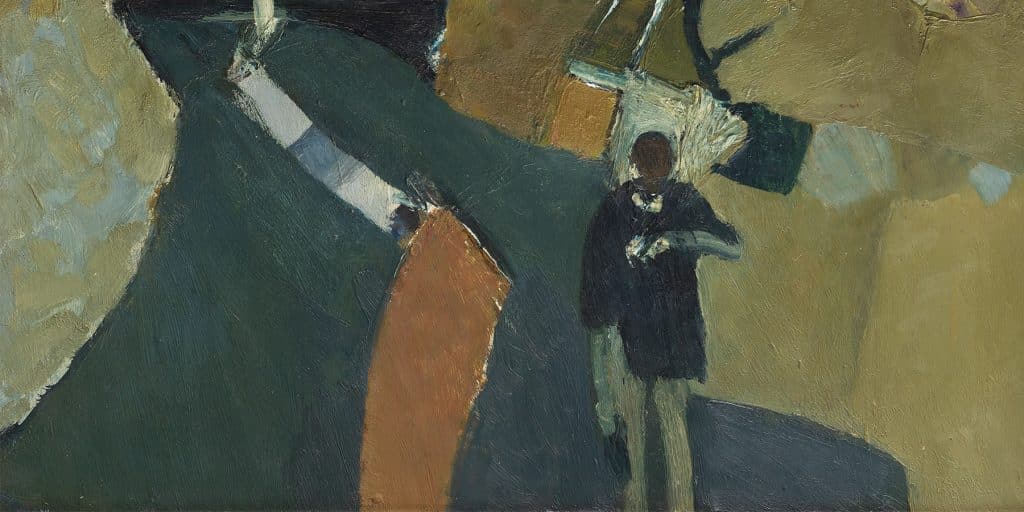

Longtime specialists in modern British art, dealers Peter Osborne and Gordon Samuel established their Osborne Samuel Gallery in London in 2005. Their booth at TEFAF Maastricht, in the Netherlands, earlier this year included Lynn Chadwick’s Beast IX, 1956, at far left above, as well as piece by Frank Auerbach, René Magritte and Barbara Hepworth. Top: The subject of the gallery’s current show, up through July 12, Keith Vaughan painted Road to the Sea between 1953 and 1958.

A titan of modern British art, long championed by the gallery, Hepworth is seen here in 1953 with one of her works. Photo by Carl Mydans/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

After falling out of fashion with the arrival of Pop art in the 1970s, the work produced in the 25 years after World War II is experiencing a revival. This is thanks in no small part to the unwavering enthusiasm (and steady nerves) of Peter Osborne and Gordon Samuel. The duo has long championed the art of that period, created by such painters as Terry Frost and William Scott, sculptors like Lynn Chadwick and Kenneth Armitage and graphic artists like John Craxton. The dealers provide context, too, also showing such prewar figures as the Expressionist David Bomberg and the later School of London powerhouse Frank Auerbach.

Osborne Samuel’s offerings at TEFAF, which included pieces by Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth as well as Chadwick and Keith Vaughan, looked as fresh as if they had been made today, even though most were created some 50 years ago.

Three Standing Figures, 1955, by Lynn Chadwick

The two dealers have been champions of modern British art for nearly as long, and they make a well-balanced team: Osborne’s special interest is sculpture, Samuel’s painting and graphics; Samuel is soft spoken and self-contained, while center stage appeals to Osborne. Both are passionate about the genre and have long believed that wide recognition of artists requires the active support of a gallery.

At home in the UK, as well as abroad, there was initially a strong positive response to these artists. Their febrile work graphically expressed the grief, horror, guilt and shattered certainties produced by the war and its aftermath. Critics used such phrases as “iconography of despair” and the “geometry of fear” to describe sculpture by Chadwick and Armitage; painters like Vaughan were torn between a desire for the stability of tradition (figuration) and the allure of radical change (abstraction).

In the 1970s, after modern British art had largely fallen out of favor, replaced by Pop art, Osborne visited Chadwick at Lypiatt Park, his part-medieval country house in Gloucestershire. “When I first met him, he was not talking to anybody at all, because the world had passed him by,” Osborne remembers. “He was sitting in his castle sulking.” Photo by John Knoote/Associated Newspapers/Shutterstock

At the 1953 Venice Biennale, MoMA’s inaugural director, Alfred Barr, bought Chadwick’s 1952 Barley Fork, an arresting, lethal-looking take on a vintage farm tool. Peggy Guggenheim purchased the 1951 version of Armitage’s People in the Wind, a huddled group of figures who resemble trees worn and bent by long exposure to gale force wind. (She later acquired three other iterations of the sculpture.) Nelson Rockefeller, too, became a major modern British art collector.

At the 1956 biennale, Alberto Giacometti was tipped to win the International Sculpture Prize, but it went to Chadwick. His powerful, unnerving 1956 plaster Beast — its formidable body balanced on slim tapering legs without feet — was on the cover of the catalogue for the British Council’s sculpture exhibition, which toured the world that year and the year after. (Osborne Samuel offered a 1957 bronze cast of Beast, from an edition of six, at TEFAF.)

Theseus and the Minotaur, 1950, by Vaughan

By the 1970s, however, people were longing for something new and more high spirited. (Today’s anxious mood may contribute to the renewed interest in the work.) Artists took their fall from favor hard. During this time, Osborne was sent by the gallery where he was working to court Chadwick at Lypiatt Park, his rambling, part-medieval country house in Gloucestershire. “When I first met him, he was not talking to anybody at all, because the world had passed him by,” Osborne recalls of the artist, who was then approaching 50. “He was sitting in his castle sulking.” Nevertheless, the dealer formed a bond with Chadwick, whose work he has promoted ever since.

In 1951, Vaughan painted a mural for the Dome of Discovery at the Festival of Britain. Photo by Derek Berwin/Fox Photos/Getty Images

“I did shows in America,” Osborne says. “We helped organize a show at the Hakone museum, in Japan. We did many shows in Caracas.” Indeed, South American collectors appear to have had a special affinity for the artist’s work. “Back in the day, you went to Venezuela, and they’d never heard of Henry Moore, but Chadwick was god,” the dealer remembers, adding that, on the North American front, entrepreneur Phil Berman “bought one hundred Chadwicks and built a museum for them in Philadelphia.” (Berman died in 1997; the Chadwicks are housed with his collection at Ursinus College, his alma mater.)

Osborne established his own gallery with Samuel in 2005, and since then, the pair have shown their modern British art internationally at fairs and biennales, in addition to mounting a regular schedule of exhibitions in their Mayfair space, overlooking Bond Street. With their decades of expertise in and engagement with the genre, Osborne and Samuel are aware of who owns what — crucial when promoting artists who are dead. This knowledge was especially important for planning their current show, “Keith Vaughan: Myth, Mortality and the Male Figure,” on view until July 12. Vaughan’s production was relatively limited, and those who own his work are often reluctant to let go of them. “We have one collector who is in his late nineties,” says Samuel, “and I have been trying to buy his Vaughans for ten years. I still can’t get him to sell.”

Reclining Figure, 1945, by Henry Moore

Despite these difficulties, the gallery managed to gather paintings, gouaches and drawings in a show whose ambitious scale has excited keen interest. Well before it opened, earlier this month, a third of the readable, scholarly catalogue’s print run of 1,000 copies had sold. Vaughan’s subjects were often naked males, alone, in couples or groups. His extraordinary diaries — almost a million words in all — detail a life filled with guilt and shame about being what he called “a member of the criminal classes.” (Homosexuality was illegal in England until 1967.) He committed suicide in 1977, at the age of 65. Some 40 years later, Vaughan’s work was included in the Tate’s “Queer British Art” exhibition. There, it exercised a strong appeal, as it does again now at Osborne Samuel, for a new generation, including those at last able to be both out and proud.

Talking Points

Peter Osborne and Gordon Samuel share their thoughts on a few choice pieces.