October 28, 2018Paul Fortune overhauled the interiors of the Sunset Tower Hotel, including the one shown above, in 2005. He also updated the Tower Bar, insisting on a new lighting design that, he writes, “flattering to all, became so renowned that it was even mentioned in a Vanity Fair editorial,” crediting it with the success of their annual Oscar party (photo by Tim Street-Porter). Top: Fortune designed this Paris home’s dining room, which is included in his new book, Notes on Décor, Etc. (photo by François Halard).

Anyone who opens Paul Fortune’s new book, Notes on Décor, Etc. (Rizzoli), thinking it will be another ode to the luxe life is in for a surprise. The British-born designer arrived in Los Angeles in 1978 and swiftly segued from creating album covers and sets for music videos to crafting interiors for boldface names, who came to include Marc Jacobs, Sofia Coppola, Aileen Getty and Dasha Zhukova. He was the designer of and a partner, with Michèle Lamy, in the ’40s-noir Hollywood hot spot Les Deux Café; he designed the elegantly understated interiors of the Sunset Tower Hotel, including the famed Tower Bar, in 2005; and it was his idea to put a 1959 Cadillac on the roof of the Hard Rock Café at the Beverly Center.

Fortune is thus particularly well placed to cast a critical eye on his trade, and he pulls no punches in expressing his opinions. The explosion of interest in design, he writes, has pushed authenticity into the shadows, and our obsession with lifestyle has spawned what he calls “Nightmare-on-West-Elm-Street disease.” But even before the rise of design as a social-media juggernaut, Fortune, in a 1997 interview in the Los Angeles Times Magazine, declared that his job as a designer was “quality control,” adding, “We must stop the reversion to the lowest common denominator.”

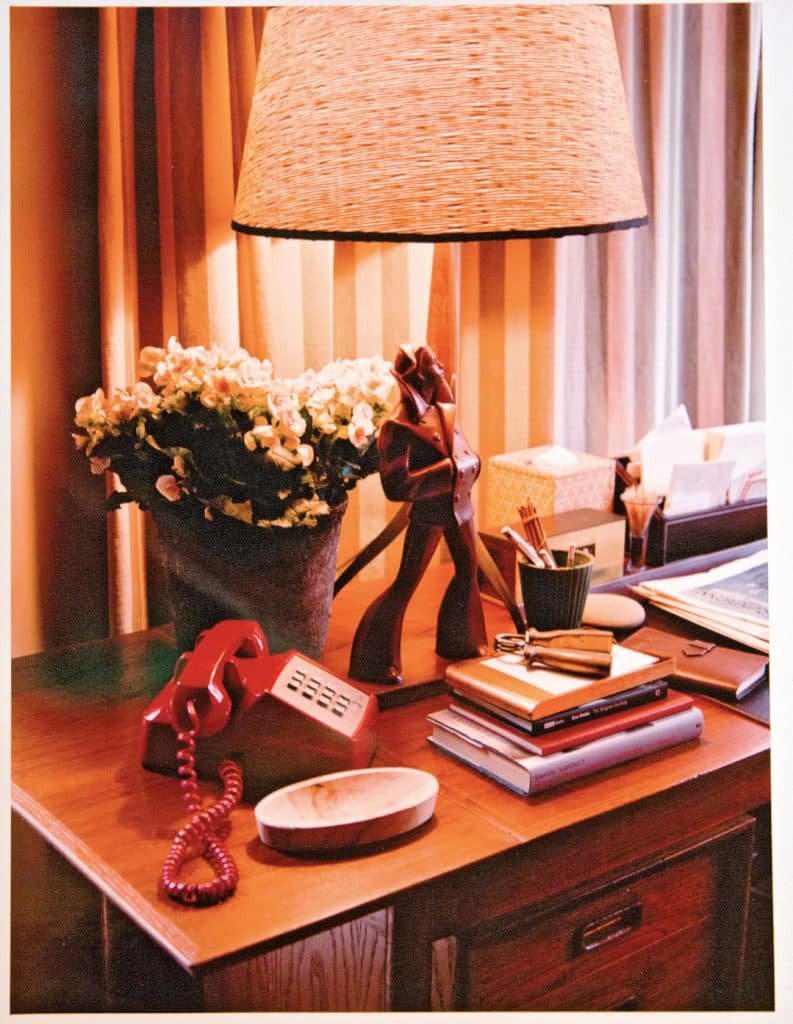

In the volume, which Fortune conceived as a kind of note- or scrapbook, he lists his pet peeves. These include “look at me” rooms filled with the art du jour; spotlights; noisy, trendy restaurants and those that don’t use white tablecloths; scented candles made of paraffin instead of beeswax; being told what to do, a reaction, in part, against his Jesuit education. (Among his likes are bedrooms with views and wood-burning fireplaces, an armchair near the bathtub for visitors, a well-appointed drinks tray and Henry Dreyfuss’s classic 2500 Touch Tone phone. “I love a landline and always will,” he says.)

His occasional curmudgeonly pronouncements, however, are those of an idealist rather than a snob. Fortune genuinely aspires to create the backdrop for a life well lived. “Interiors should be comfortable and reveal themselves slowly and sensually,” he writes, adding that “a successful room has layers that have been applied over years.”

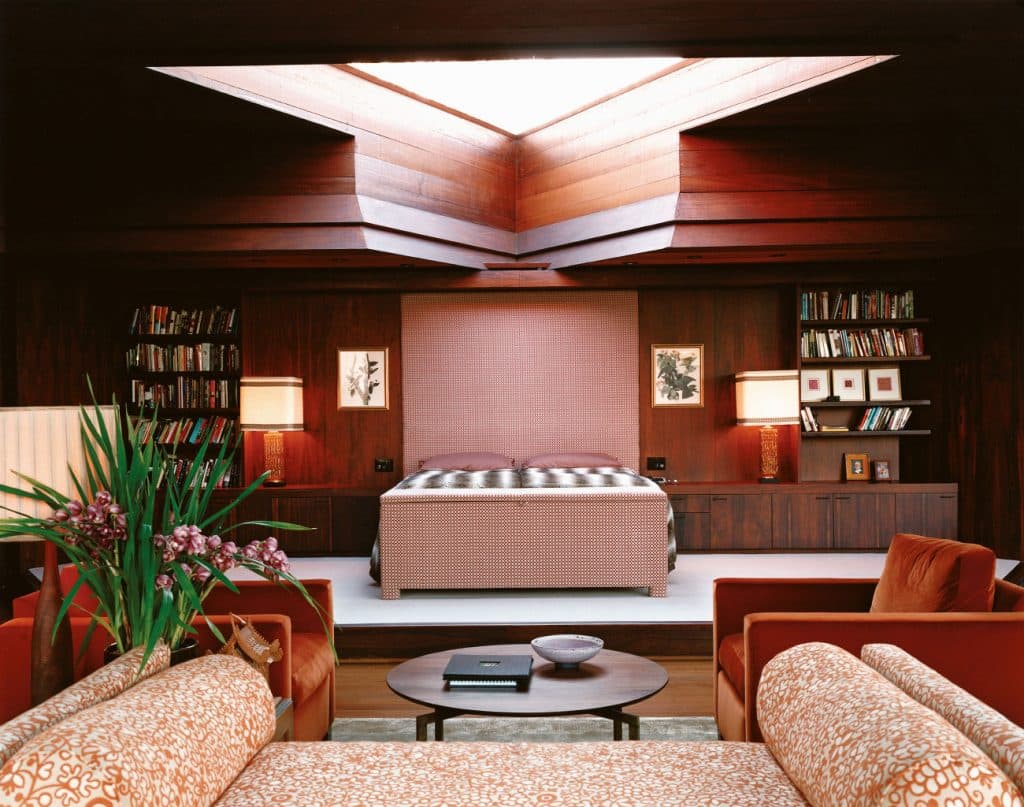

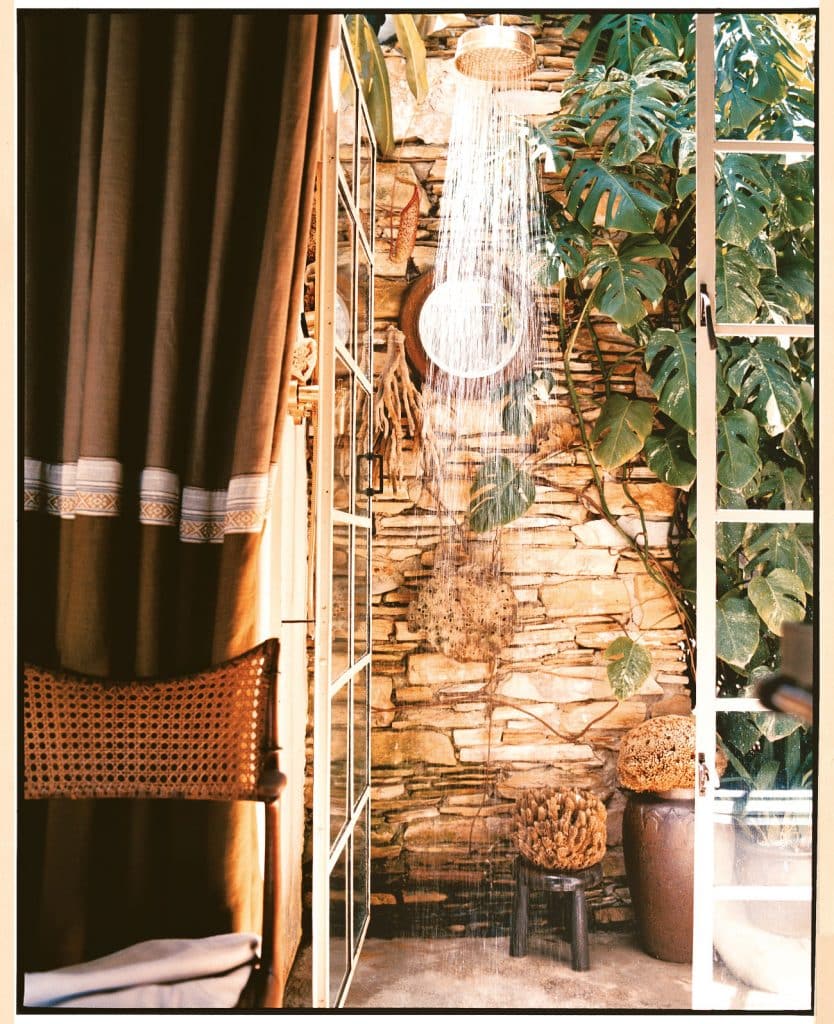

These interiors, whether in a glamorous art-filled Greenwich Village townhouse or the architecturally dramatic 1970s home that once served as bachelor pad of basketball legend — and legendary bachelor — Wilt Chamberlain (the book does not identify any of the designer’s clients), are all about authenticity. Fortune’s aesthetic is 20th-century modern, but it welcomes Art Deco and the archetypally plain furniture of the contemporary artist/designer Roy McMakin. Fortune’s palette is consistently neutral but never bland; he favors warm woods, sensuously textured fabrics and patterned carpets. The last are often rare examples from the likes of C.F.A. Voysey and Märta Måås-Fjetterström, which he has a talent for hunting down. Perhaps the best known of all Fortune’s projects is the house in Laurel Canyon where he lived for 35 years before selling it in 2013. With its double-height stone-walled living room, beamed ceilings and wrought-iron mezzanine balustrade, cozy master bedroom (with its own fireplace, of course) and French doors opening from the master bathroom to an outdoor shower, it came to epitomize a casual, rather Bohemian version of the good life in Southern California.

Fortune created the interiors of the Carpinteria, California, house of photographer Dewey Nicks and his family, which was designed by architect Barbara Bestor. Photo by William Abranowicz

The British-born, Los Angeles-based Paul Fortune has spent four decades designing interiors for high-profile clients. Portrait by Dewey Nicks

It was a vision, according to Fortune, that was well within reach when he moved west. “You could rent a house in the hills for $300 a month. Drinks were $2.50. The sun shone more than I knew was possible. . . . Ella Fitzgerald was at the dry cleaners picking up her dress while her driver took a smoke in the lot,” he recalls in the book, adding, “I met many of my heroes: Ed Ruscha, Joni Mitchell, Fred Astaire, Gore Vidal. Everyone was more accessible in the age before social media, believe it or not. People were less guarded.”

These days, Fortune lives about 90 minutes north of Los Angeles, in Ojai, where he shares a comfortable bungalow with his husband, Chris Brock. Their guest house is a vintage Spartan trailer to which Fortune added a pine interior — “People never want to leave,” he said in a recent interview — and they drive around in a 1967 Rolls-Royce. Fortune maintains an office and an apartment in L.A. and likes to go to the opera there. But he says “the potential of L.A. was different” when he first arrived: “The postwar cultural scene gave it an amazing aura. I arrived at the very end of that. I’d go to Rita Hayworth’s house with Christopher Isherwood. Now,” he adds with characteristic acerbity, “it’s traffic and boring people.”

Fortune’s current projects include a Manhattan townhouse for Coppola and two apartments in L.A. for the billionaire philanthropist and art collector Nicolas Berggruen. He continues to work in the style that he describes as “post-design,” stating that “I never had a ‘look.’ I like the idea of each new problem being resolved in a new way, and I want my projects to last a hundred years.”

Purchase This Book

Or Support Your Local Bookstore