October 16, 2013A chapter of the new book, Private Gardens of the Hudson Valley, is devoted to the gardens of a Thomas Phifer–designed house in Clinton Corners, New York. Top: The Ancram spread belonging to New York Botanical Garden president Gregory Long and his partner, Scott Newman, has a pond as its focal point. All photos © Monacelli/John M. Hall

New York’s Hudson Valley, a lush swath of land several hours due north of Manhattan, is celebrated for its wild, craggy terrain and its meadows, forests and farms. On a drive through the region you might easily regard its many beautiful gardens as another natural part of the landscape, as inevitable and everlasting as the Shawangunk Ridge or the broad Hudson River itself. Yet when leafing through garden writer Jane Garmey’s new book, Private Gardens of the Hudson Valley (Monacelli), one is exposed not only to a wealth of verdant spreads but also to the tremendous amount of steady, patient human effort that goes into creating them.

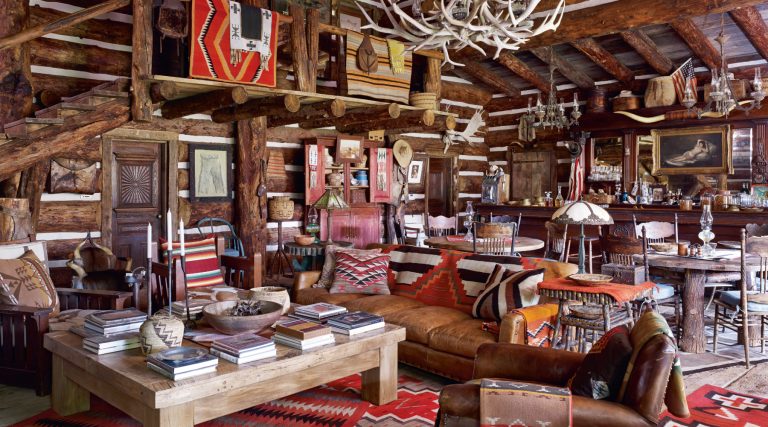

In this follow up to her book Private Gardens of Connecticut, the British-born, New York–based Garmey selected 28 highly impressive green spaces, some of which might be known to garden insiders, others not. Accompanied by dozens of stunning color photographs by John M. Hall, the book creates a good sense of what it’s like to gaze out the window of homes of all sizes and styles, or wander lazily along meandering paths leading to thickets of blossoms and emerald ponds. Some properties on Garmey’s radar are storied mansions once belonging to legendary figures – Gore Vidal’s former neoclassical home, Edgewater, in Barrytown, for instance – and now lovingly restored or accented by the current owners. Others are more like blank canvases spotted by discerning eyes and then miraculously transformed. In one case, for example, the owner had been shopping for real estate in the area when he spent that night at a run-down bed-and-breakfast in Millbrook. He saw the beauty in the bones of the property – which included an old swimming pool filled with broken, rusted machinery – and ended up purchasing it.

The architect and designer Paul Mayen originally created an enormous Garrison spread — complete with pyramids, pavilions and waterfalls — that’s now owned by the gallerist John Driscoll and the artist Marylyn Dintenfass.

The theme of transformation is central to garden writing, and Garmey homes in on the heart of these before-and-after tales. These are not overnight changes achieved by armies of landscapers. Rather, Garmey, a passionate gardener herself, is interested in those folks who have gone through the long process of imagining all the complexities of a garden – its structure, palette, texture, mood and style – and then slowly and patiently created and nurtured it as nature catches up to their vision. In some cases, landscape designers and gardeners came in to assist (some of these properties go on for hundreds of acres), but, for the most part, the owners have been deeply involved in the outcomes of their landscapes, often getting their own hands dirty on a daily basis. Some are professionals or experts – including Scott Canning, Wave Hill’s director of agriculture; Gregory Long, who oversees the New York Botanical Garden; or Amy Goldman, who has won dozens of prizes for the vegetables she grows in her sprawling kitchen garden – and to see how they have figured out how to tame nature, or at least guide it, is inspiring.

Garmey paints vivid portraits of the gardens’ owners by describing their decision-making and sharing personal anecdotes. We learn, for example, the cringe-inducing story of how 22 tons of gravel were accidentally delivered to one gardener’s neighbor’s house and had to be moved over “wheelbarrow by wheelbarrow.” As elegant as the results can be, gardening is a dirty, exhausting job, which makes these stories all the more interesting. One of the best things about the book, though, is its portrait of the 21st-century splendor of a region that has historically loomed so large in the American imagination – as the rugged, resplendent paradise of the Hudson River School painters, and as the 19th-century rural hub of such high-society clans as the Vanderbilts and Rockefellers. Few places mix that kind of civility and rawness, and Garmey captures it well.