Based in Brazil’s northeastern state of Paraíba, Sérgio J. Matos crafts all his furniture by hand with the help of local artisans. Each piece reflects an aspect of quintessentially Brazilian culture. Top: In a São Paulo living room by Cristiane Guerino, Matos’s Arreio lounge chairs, composed of saddle straps fastened around a steel frame, take center stage. All photos courtesy of Sérgio J. Matos and portrait by Thayse Gomes

March 8, 2020Sérgio J. Matos isn’t like other furniture designers. Rather than moving to a big city with a booming design scene, the Brazilian native has chosen to live in the country, working with local artisans in the northeastern state of Paraíba to craft his intricate furniture. Now, after nearly two decades in the business, Matos’s studio is opening its first brick and mortar store, in São Paulo in May.

Matos’s playful pieces have won numerous design accolades, including the 2012 iF Design Award in Germany and the 2018 International Contemporary Furniture Fair’s award for outdoor furniture in New York. But building whimsical swings, chairs and tables using complex weaving techniques wasn’t always his plan.

Born in Brazil’s westernmost state, Mato Grosso, in 1976 to a butcher and a housekeeper, Matos spent his childhood building toys with his sister using fibers from the buriti palms in the Amazonian wetlands. He earned a degree in advertising and marketing from the Universidade de Cuiabá but during his time there found himself drawn more toward creative pursuits than business. So, after graduating, he immediately enrolled in the five-year furniture design program at the Universidade Federal de Campina Grande, in Paraíba.

Mimicking the shape of endangered elkhorn coral, which is still relatively abundant off the coast of the Brazilian state of Acaú, Matos’s Acaú armchair takes more than two months to hand craft.

The cross-country move was a defining factor in his budding career. “Anyone who leaves any state in Brazil and goes to the northeast,” Matos says, “ends up discovering a new world” — one untouched by technology, industrialization and society. The Paraíba-tourmaline-colored ocean waters, silky quartz-sand dunes, crystal-clear lagoons and unimaginably colorful Amazonian rainforests of his new home became touchstones for his work.

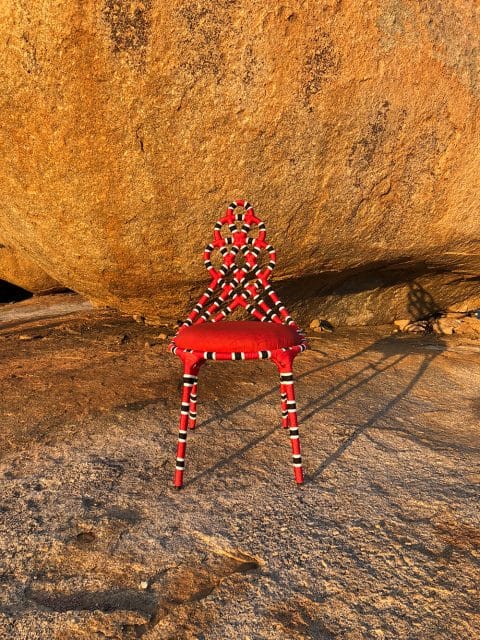

The sleek, twisted shape of Cobra Coral chair recalls its namesake Brazilian coral snake.

Matos immersed himself in Paraíba’s local artisanal culture, incorporating the region’s traditional craftsmanship as a crucial element in his process. “Whenever I design a new product, my research always begins with some theme that is linked to Brazilian culture or identity,” says Matos, whose pieces evoke the distinctive traditions of the country’s states.

His vivid colors, for instance, recall the Maracatu Nação parade, in Pernambuco, in which throngs of drummers and dancers don bright costumes and elaborate headpieces to celebrate Brazil’s abolition of slavery. The pieces’ coastal feel, meanwhile, recalls Festa de São João, Paraíba’s version of Coachella, one of the state’s longest-running festivals, which embraces the folk music and dance genre forró. And their unmistakable wry humor brings to mind Bumba Meu Boi, the interactive satirical dance plays that originated in Maranhão and are now performed nationwide.

Shaped like the carambola, or starfruit, Matos’s Carambola stool is one of the designer’s easier pieces to craft. The two-step process consists of building a steel frame and wrapping it in naval rope.

Also evoked in nearly all Matos’s pieces is Brazil’s abundant wildlife. The Cobra Coral chair, for instance, takes its coiled shape and tricolor palette from the native coral snake. The bold doughnut-shaped Acaú armchair is modeled on actual coral, the elkhorn variety, which, although endangered elsewhere, is still relatively abundant in the coastal Brazilian province of Acaú. Making these pieces is a two-month process, in which one craftsperson creates the frame while another hand wraps cotton around 600 pieces of cut and twisted wire, forming modules that still more artisans glue and wrap onto the metal frame.

Inspired by the 1970s Movimento Armorial, which was dedicated to reintroducing and repurposing once-popular materials and objects, the Arreio chair gives straps designed to secure a saddle on a horse a new, artistic function.

Engagement with the local craft culture has been important to Matos from the beginning of his career. As a young designer, he convinced SEBRAE, a nonprofit that supports small businesses and entrepreneurs, to hire him as a consultant on a project aimed at promoting the artisanal work of indigenous communities. He could use his marketing background and design knowledge to help local artisans make furniture and climb out of poverty. “I believe that the success of my work is related to the way people see the pieces,” he says. “Even though they’re technically new, they refer to a culture that has already lived and continues to live.”

Collaborating with indigenous communities impacted the way Matos saw shapes, patterns and color, and he began to incorporate their traditions into his own designs. The Chita swing, for instance, is named for the wild floral chita (Portuguese for “chintz”) fabric that made its way from India to Brazil in the early 19th century and became a staple of festivals like Carnival. The whimsical piece resembles a hanging bouquet of the colorful flowers that adorn traditional 19th-century chita.

Making the swing involves just two steps: building an aluminum armature and wrapping it with naval rope. The same simple process is used for such other fanciful pieces as the Chita swing, Carambola stool and Taturana bench, all hallmarks of Matos’s early career.

Having put together a hefty, and growing, collection of Amazonian-inspired seating and tables, Matos was eager to show it off at Milan’s Salone del Mobile, the Super Bowl of design, and so reach an international audience, as his legendary compatriots Lina Bo Bardi and the Campana Brothers had before him. In 2009, his portfolio landed on the desk of one of SaloneSatellite’s veteran curators, Marva Griffin, who sent Matos a letter expressing her interest in meeting him and seeing his unusual pieces.

The Taturana bench borrows its form from the tiny Amazonian taturana caterpillar, whose name means “burning bug” in the ancient Tupi dialect. Matos admired the symmetry of the creature’s segmented body and replicated it using naval rope on a stainless-steel frame.

“She was in São Paulo, and I had no way of getting all the way there from the northeast,” Matos recalls. “However, hope wasn’t lost because now that I had her contact info, I sent an email saying everything I would have told her at our meeting.”

That was all Griffin needed. Shortly after receiving his message, she responded with an invitation to exhibit in the 2010 Salone del Mobile. “Salone, for me, was a game changer,” says Matos, “because it put me on the map and my pieces on the international market. Before Salone, I couldn’t sell my work to stores outside of Brazil, nor could I design for the industry.”

Since then, Matos has shown at Salone four times, including for the studio’s 10th-anniversary, and has produced a body of work that continues to validate his decision to step away from a marketing career in favor of a passion project that changed his life.