May 25, 2015Mudai (Untitled), 1960. Top: Shigeki Kitani with peer Saburō Murakami’s work Arayuru Fūkai (Whatever View You Like) at the second Gutai Yagai Ten (Gutai Outdoor Exhibition) in 1956.

Like all the best dealers, New York gallerist Erik Thomsen keeps an open mind about discoveries outside his area of expertise. Although a renowned specialist in fine antique Japanese screens, with many museum sales in this category to his credit, he also shows luxurious Japanese lacquer, avant-garde basketry and contemporary porcelain. This month, he further expands his purview, devoting his Upper East Side gallery to a show of 33 oil paintings, three-dimensional wall sculptures and collages that re-examine the legacy of Japanese Gutai artist Shigeki Kitani (1928–2009).

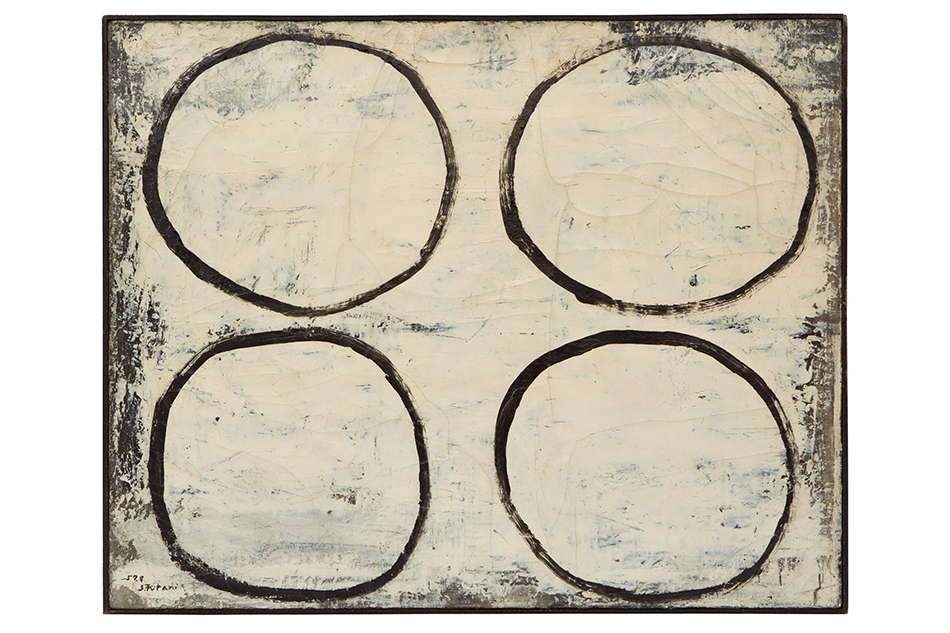

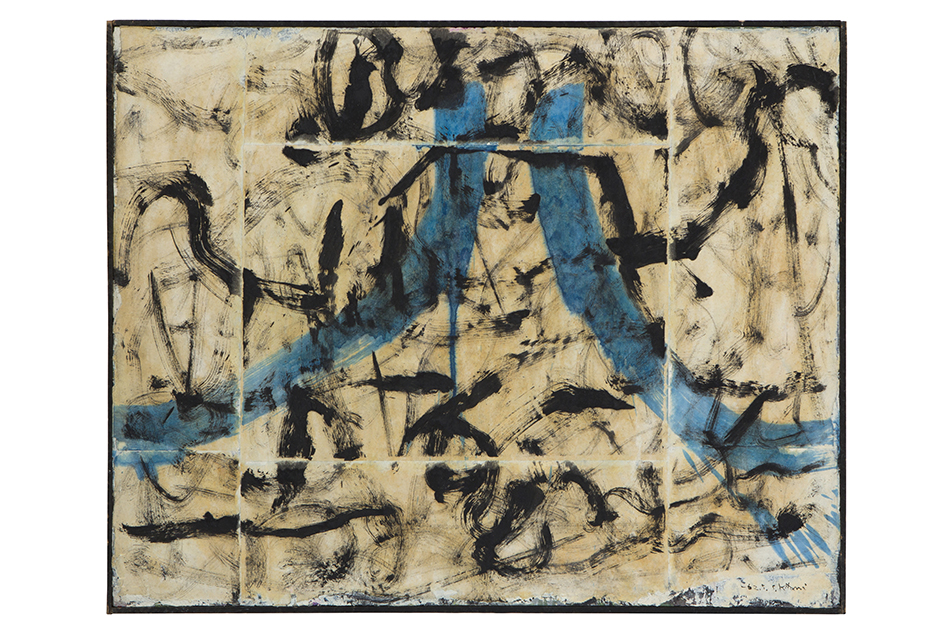

The works on view are Kitani’s early pieces, made between 1951 and 1969 — and they are riveting. The paintings are fresh, elegant and abstract. Several have large circles scratched into the background, while others have layers of paint scraped away to reveal different shades underneath; one has holes ripped in it. Another has loose tissue paper painted onto it. Some are purposely flat while others show depth; my favorite looks like a pond of tadpoles, viewed from the bottom, each creature silhouetted against the sunlight.

The attention-grabbing three-dimensional canvases, meanwhile, padded to represent female torsos, are painted in concentric stripes of bright red, yellow, blue, purple and green. Pieces from this “Torso” series, created in the mid-1960s, are among Kitani’s best-known works in Japan. In fact, although the artist is one of his country’s most celebrated artists — he was included in a show, “Gutai: The Spirit of an Era,” at the National Art Center in Tokyo in 2012 — he is little known in America and was not represented in the Guggenheim Museum’s groundbreaking 2013 presentation “Gutai: Splendid Playground,” which was curated by Ming Tiampo and Alexandra Munroe. (Shown the new 88-page Kitani catalog last week, Munroe said, “Kitani is among the lesser known of Gutai’s 59 members, but clearly he is not a lesser artist than many of them. The show is a great discovery for Western audiences and is, on Erik’s part, a labor of love.”)

The artist in 1967 working on his “Torso” series, a group of works combining painting and sculpture that earned him international acclaim. Two of these pieces are in Erik Thomsen’s current show.

After Kitani’s death in 2009, his son, Tenpei, retrieved about 30 works from the Ashiya City Museum near Osaka, where they were on loan but not on view. Thinking the works needed a better home, he decided to sell them, and after much research contacted Erik Thomsen. Kitani did not start out as a revolutionary painter. After World War II, he began writing modernist poetry and enrolled in a conservative art school in Kyoto. As the one figurative painting featured in Thomsen’s show makes clear, he was, in fact, an excellent draftsman. But after he graduated in 1952, he could not ignore the fact that the postwar Japanese avant-garde was in full blossom. “He came under the spell of Jiro Yoshihara, the charismatic, radical co-founder of the Gutai Art Association,” Thomsen says. In 1956, in his famous Gutai Art Manifesto, Yoshihara wrote that the art of the past was “fraudulent.” Elsewhere he declared, “Do what no one has done before.”

Indeed, as Thomsen explains, “the Gutai movement involved experimentation with materials: Gutai literally means ‘concreteness.’ ” Gutai artists used their bodies to play with materials and to create chance encounters. They danced, played music, painted freestyle and made sculptures to dive through — long before artists in the West developed the concept of “Happenings.” (In the 1930s, Yoshihara was already staging designs for fashion shows, doing sets for dance performances and creating opportunities for audience participation.)

Sakuhin (Work), 1958, is just one of more than 30 works now on display in the exhibition “Shigeki Kitani: Early Works,” on view at Erik Thomsen through June 20.

Shiraga Kazuo is probably the best-known Gutai painter from the 1950s, celebrated for painting with his feet while swinging from a suspended rope. (An important show of his work recently closed just up the street from Thomsen, at the Dominique Levy Gallery.) Other practitioners hurled their bodies through giant pieces of paper set in suspended frames. “Gutai expresses a physical embodiment or actualization of substance, as opposed to the abstractions of thought,” Munroe wrote in the catalog for the Guggenheim’s 2013 exhibition, adding that its most spectacular characteristic was “the reciprocity between physical action (throwing, thrashing, breaking, exploding, tearing, pouring) and raw matter (wet paint, sand, tar, mud, smoke, chemicals).”

Kitani did not formally join the movement until 1965, but already by 1956 he was participating in Gutai group shows. While not doing actual performance art, Kitani treated the surface of a canvas the way an action painter would: scratching its built-up layers, cutting the canvas, even stuffing it.

The work is pure Gutai, and, as such, it offers a fascinating glimpse into a decade of unfettered creativity in postwar Japan.