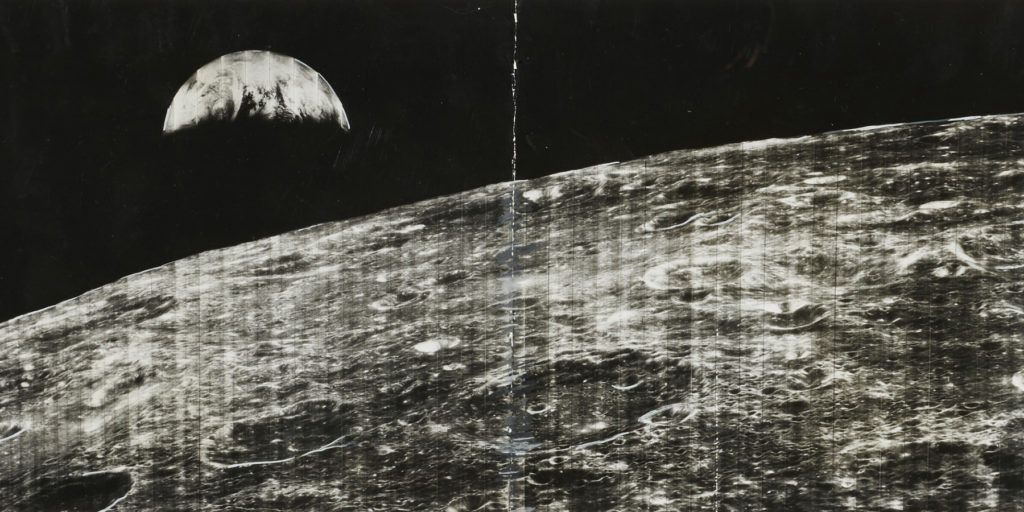

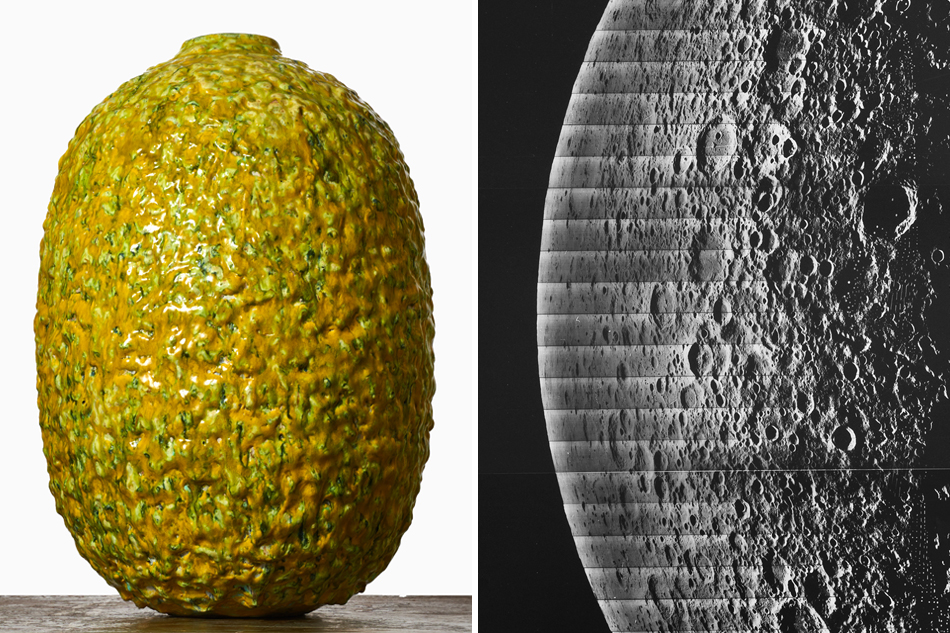

June 13, 2016On view through July 30 at New York’s Jason Jacques Gallery, “The Orb” pairs heavily glazed, moon-influenced stoneware vessels by Danish ceramist Morten Løbner Espersen (above) with prints of lunar landscapes shot by NASA satellites in the late 1960s (portrait © 2012 Søren Rønholt). Top: The First Photo of Earth as Seen from Lunar Orbit was snapped on August 23, 1966, by the Lunar Orbiter I. All photos by Robert Cass, courtesy of Jason Jacques Gallery, unless otherwise noted

Call it a cosmic coincidence. Both the New York–based dealer Jason Jacques and Copenhagen-based ceramic artist Morten Løbner Espersen had been building bodies of work based on the moon, but each was working in isolation. Jacques, best known for his representation of boundary-pushing ceramists, had recently been smitten with an entirely different medium: photographs of the moon’s surface taken by NASA lunar orbiters in the 1960s. Espersen, meanwhile, was completing an artist residency in Japan when he became inspired by last September’s blood moon eclipse.

“He sent me a picture of his first pot from his time in Japan, and it said, ‘Greetings from Shigaraki. I fired this on the blood moon,’ ” says Jacques, who began selling Espersen’s work about four years ago. “It was this amazing moon pot, all red and white. I thought,‘Wow, this could be a fantastic pairing.’ ”

The result of this overlapping interest between artist and gallerist is “The Orb,” an exhibition of these two materially disparate yet thematically complementary bodies of work that is running at Jacques’s Upper East Side gallery through July 30. The show represents the dealer’s first full-fledged foray into photography, but the images involve no conventional photographer.

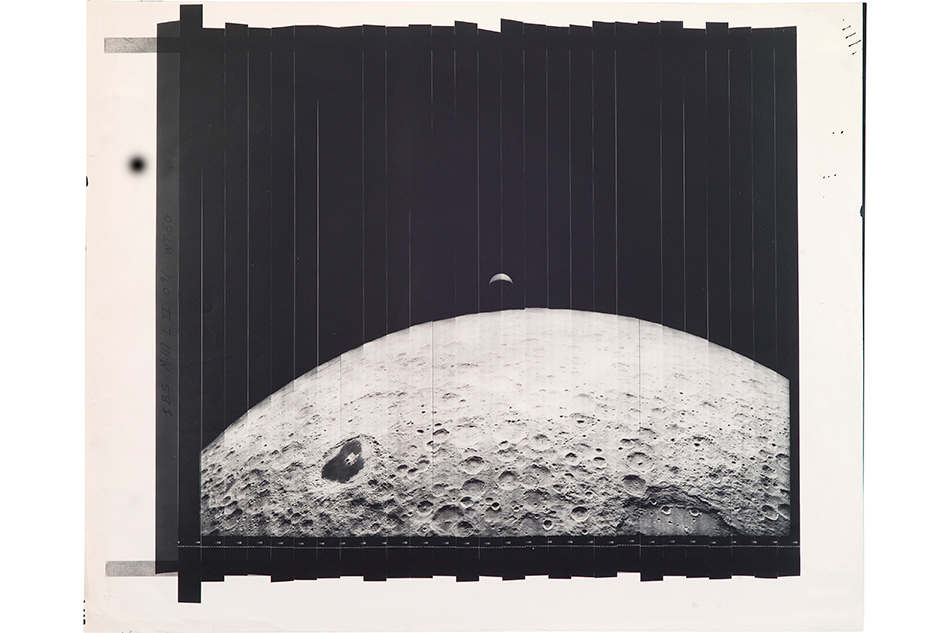

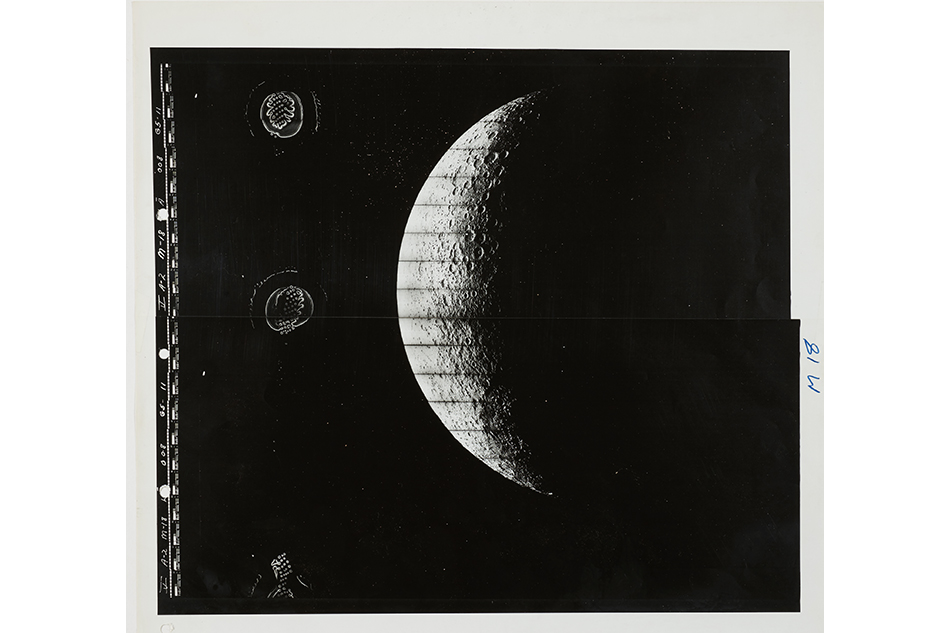

“The artist is a robot, and the story behind it is the coolest, sexiest, most romantic thing ever,” says Jacques. In 1966 and ’67, he explains, NASA sent orbiters into space to search for landing sites for its first manned mission to the moon, which, of course, was eventually completed by Apollo 11 in 1969. “The robots would photograph the surface and develop the film directly inside the orbiter. Then, a scanner in the unit would scan these images and transmit the data back to NASA. The folks there would re-create the images from tiny strips,” he says, noting the lines that can be seen crossing the images today.

The resulting large-scale, ghostly prints show a deeply textural landscape pockmarked by craters. For the most part marked with the legend “Langley Research Center” or “U.S. Army Corps of Engineers,” they were used by government scientists and sold to universities and observatories. About half the photographs in the show are from Jacques’s own collection, while the other half come from the Daniel Blau gallery in Munich. “It’s scientific photography that’s one of the most beautiful things,” says Jacques.

Upon seeing the first of the many moon vessels that Espersen would produce, gallerist Jacques — who had been collecting the NASA moon shots for years — recalls thinking, “Wow, this could be a fantastic pairing.”

When Espersen sent him a photo of his first “moon vessel” last fall, it seemed serendipitous, yet also perfectly natural. “He’s one of the greatest glaze artists in the world, and his surfaces have always been very lunar,” says Jacques. But the forms represent a departure from Espersen’s recent “Horror Vacui” series, which comprises wildly organic, almost anthropomorphic sculptures. Here, he has returned to deceptively basic forms encrusted by a multitude of thick, multicolored glazes that he layers on through several firings, often at varying temperatures.

“I was in a foreign place where everything was kind of unusual,” Espersen says of his time in Japan, “so I felt I needed to do something as simple as possible.” This meant producing spheres and slightly more ovoid pots. “From my perspective, using the clay as a valueless material — but then giving it texture and adding surface, color and structure — that’s where I’m able to lift something that is nothing in particular into something that is touching and maybe resonates on a deeper level.”

Espersen, who began working with clay as a child and never stopped, served as a professor at the School of Design and Crafts in Gothenburg, Sweden, from 2004 to 2011, but he says teaching students the conventions of ceramics only made him want to experiment more. “I fell in love with a material that’s pretty difficult to control,” he admits. “I try to use my experience but also to forget it, to force myself into doing something that may be a little surprising. I ask questions of the clay, and it gives better responses than I could think of.”

His relationship with his gallerist proved just as surprising. “Neither Jason nor I was aware of what the other was doing,” Espersen says. “Suddenly, there was this meeting no one anticipated, and it was obvious to everyone that this was the way it was supposed to be.” The universe works in mysterious ways.