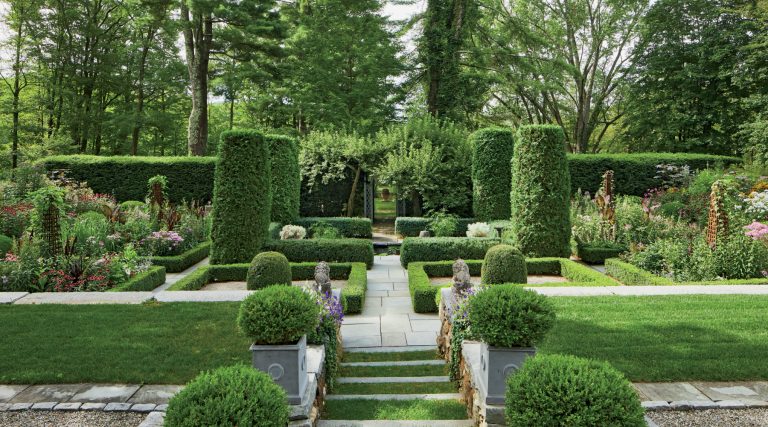

August 21, 2017Tania Compton highlights 35 verdant properties in her book on exceptional private English gardens (portrait by Sabina Rüber). Top: The Topiary Garden at Ferne Park features Stephen Pettifer’s Triton fountain, which is inspired by Bernini’s in Rome. Photo by Andrew Lawson

In The Private Gardens of England, Tania Compton, writer, garden designer and former editor at British House and Garden, gives readers the inside scoop on 35 of the loveliest private gardens in Britain. Don’t look here for adorable cottage plots or postage-stamp urban backyards. The oases highlighted in this remarkable book (published in the U.K. a while back but not widely distributed in the United States, which is why it initially escaped my notice and why I’m doubly pleased to have discovered it now) are top drawer in every sense. They show there’s still a certain set in that country with the time, inclination and considerable means to make, restore and maintain gardens of unimaginable scope and beauty.

The properties that Compton has chosen are tended by full-time gardeners (usually more than one) and exist to complement substantial, architecturally distinctive houses. Her book is not portable — at 458 pages, it’s huge and heavy. However, as the saying goes, it’s worth its weight in gold, not only for its luscious photographs, taken by many of Britain’s best photographers, but because Compton has cannily invited the gardens’ owners to write about them. We get to understand that our tour guides are passionate, knowledgeable and intimately involved. Their colorful, conversational descriptions feel like one-on-one tours. All that’s missing is a glass of champagne!

Readers get an up-close look, for instance, at Ven House, a formal red-brick 18th-century Georgian mansion in Somerset that was purchased in 2007 by the designer Jasper Conran. The original garden, which dates to the 19th century, is still intact and contains two walled gardens, a sunken parterre, topiary, an elegant orangery and a tall conservatory. Although not in need of complete restoration, it required what Conran describes as “softening and cajoling back to life.” He explains that his job is all about “editing and reappraising” this property, which is extremely grand and, Conran confesses, “utterly irresistible.”

Haseley Court’s topiary chess set adjoins the Oxforshire countryside. Photo by Andrew Lawson

The initial plan had also been maintained at Haseley Court, in Oxfordshire, when Mrs. Desmond Heyward (we never learn her first name) and her husband purchased the estate in 1982 from the eminent American designer Nancy Lancaster, of the legendary firm Sibyl Colefax & John Fowler. Lancaster created the garden in the 1950s and ’60s. Recognized as one of England’s greatest mid-century gardens, it is a mixture of formal and informal, with a walled garden, woodlands, hornbeam hedges, boxwood topiary and the much-lauded tunnel formed by yellow laburnum. Many people would have been daunted by the prospect of taking over this property. Not the Heywards. They are thrilled at their good fortune yet know to make changes when needed, and they “do not keep the house and garden as a memorial to Nancy.” Instead, she writes, “Her original design is very much in place not because we feel we have to preserve it, but because we love what she created.”

When Mary-Anne Robb came to Cothay Manor, a 15th-century house in Somerset, she faced a different situation. Here, only the bones of a 1920s Arts and Crafts garden remained, and it was in need of almost total restoration. Its dominant feature was a long yew walk that opens into many garden rooms, and Robb’s first task was to gut their interiors to make new gardens, all color coded and some of them named for her relatives. Robb is a formidably experienced plantswoman, and her creation has a dreamlike quality. She is also practical and understands her work will never be finished because, as she points out, “[i]n a garden if you live ‘above the shop’ there is always something to do.”

In an area of Compton’s Spilsbury garden that she refers to as “the Playpen,” she grows an annual mix of Ammi majus and cosmos. Photo by Sabina Rüber

A different kind of restoration was achieved at Boughton House, in Northamptonshire, when the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensbury asked Kim Wilkie, one of the most interesting English designers at work today, to bring coherence to the parkland around his ancestral home. Wilkie’s forte is creating shapes and forms within a landscape. At Boughton, he came up with Orpheus, a massive 160-square-foot inverted grass pyramid with a sunken pool at the bottom that represents Hades and plunges to a giddying depth of 23 feet. The result is an astonishingly beautiful work of art in a glorious pastoral setting.

Ferne Park, in Wiltshire, belongs to the Viscountess Rothermere. The property has amazing vistas, but the old house was gone when she and her husband bought the land in 1999, and they engaged Quinlan Terry to design a new one for them. Upon its completion, Rothermere realized that “[h]ouses, like people, generally look better when clothed.” Accordingly, she went to gardening school, read books and, with the help of Rupert Golby, made a plan for a garden. It’s hard to believe that everything here — fruit trees, kitchen garden, gates, terraces and formal garden — was added in less than 16 years.

The final chapter in the book is about Compton’s own garden, Spilsbury, in Wiltshire, which she and her husband, botanist Jamie Compton, have owned and cultivated in for 15 years. Perhaps a little less grand than some of the other properties in her book, Spilsbury is still an ambitious enterprise, having grown over the years, as she tells us, without a master plan. It is a delightful mix of structure and informality. “Nature,” she insists, “has the upper hand,” but this is not so either at her own place or in this ravishing collection of gardens she has assembled. “How lucky we were to find it,” says one of the owners says of their home. And as readers, how lucky we are that the houses were found and their gardens tended so diligently — and then captured in Compton’s wonderful book.

Purchase This Book

or support your local bookstore