Best known for his innovative glasswork, Timo Sarpaneva helped to define mid-century Finnish design. Here, he uses a hammer to sculpt Vela Bianca in Toijala in 1986 (portrait by Marjatta Sarpaneva). Top: A major retrospective of Sarpaneva’s work at the Design Museum in Helsinki includes a monumental installation of glass titled Pack Ice, produced by the glassblowers at Iittala (photo © Paavo Lehtonen). All photos courtesy of the Design Museum Helsinki

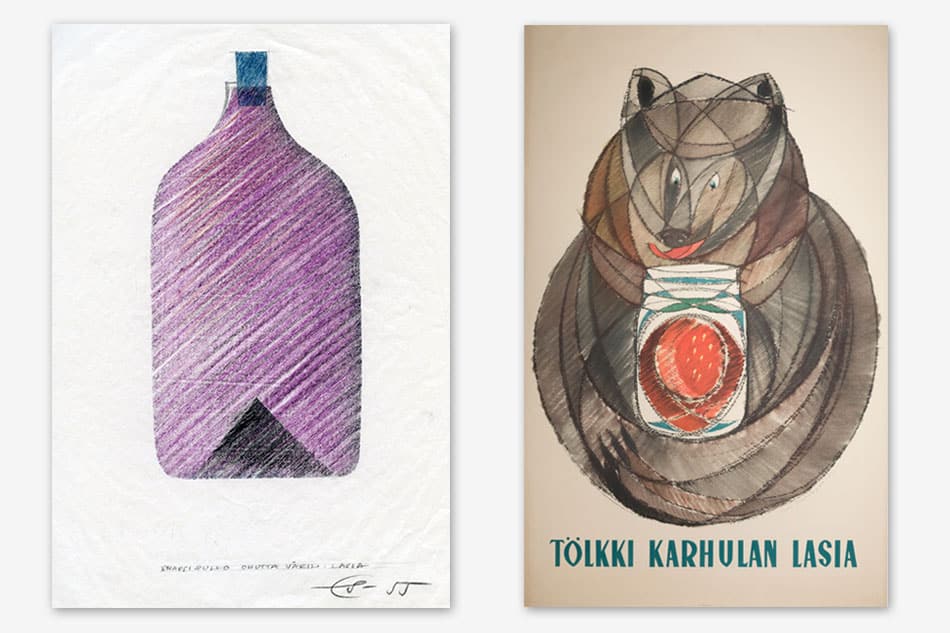

July 29, 2018You can almost hear the sound of trumpets as you enter the ambitious, revelatory exhibition “Timo Sarpaneva” that is currently on view (through September 23) at the Design Museum in Helsinki, Finland. Huge banners hang from the avenue of columns that runs from end to end of the top floor’s central hall. At first glance, the broad bands of rich, intense reds, blues, purples and greens look like a parade of Rothko paintings; in fact, they are from the Ambiente series of textiles designed by Sarpaneva (1926–2006) in 1965 to be manufactured by Tampella and Finlayson. Arrayed beneath them are some 400 works by the designer, a local legend and internationally influential for decades. The pieces are displayed in galleries — some large and open, others small and intimate — that have white walls and wooden floors painted a uniform battleship gray to provide a neutral, unifying backdrop to the eye-opening and immensely varied assembly of drawings and textiles; crockery, cooking pots and cutlery; posters and clothing; and, above all, the innovative glassware for which Sarpaneva is most famous.

Also in the exhibition are photographs that tell some of his story — among them, images of the fantastical, crowd-attracting shop windows (adorned with glass harps and butterflies hanging from invisible wires) that he created for Iittala, the company that hired him in 1950. It was there that he made his name as a glass designer, of both art pieces and usable ones. In the latter category are the colored drinking glasses and beakers of the (pre-Internet) i series, for which he created a special logo: a boxy, lower case i that sits at the center of a small blood-red circle. Simple, bold, easy to identify and jolly, it soon became the company logo and remains so to this day.

In 1996, Sarpaneva’s wife, Marjatta, began a series of video interviews with the designer in Finland and with the glassblowers of Murano in the Venetian Lagoon, where he worked in his last years. They are an entertaining addition to the exhibition; Sarpaneva had charm and was good at sharing anecdotes that are both amusing and provide insight and information. In one, he looks back at his early days and only half-jokingly says he had his sights on surpassing Tapio Wirkkala, a decade older, who then dominated Finland’s design spotlight.

It was architect/designer Alvar Aalto who, in the 1930s, first brought the expressive yet stripped-down power of Finnish design, and its merging of art and craft, to the attention of the wider world. But Jukka Savolainen, the Design Museum’s director, explains that “Finland’s Golden Age of design was the nineteen fifties.” And its golden boy was Sarpaneva.

In 1951, at the first postwar Milan Triennal, Sarpaneva, then in his early 20s, submitted an entry that intrigued the judges. A graphic-design graduate, he had given one of his drawings to his mother and asked her to embroider it on a coffee cozy. (The design and the embroidered rooster-shaped cozy share a vitrine in the first room of the Helsinki show.) The espresso-drinking Italian judges were charmed by Sarpaneva’s folkloric creation but, not familiar with warmers for ceramic coffee pots, they were puzzled about its purpose. Wirkkala quickly came to their aid — and the designer’s. He picked up the cozy and put it on his head, proclaiming it a carnival hat. His comic turn worked: Although it was Wirkkala who won three Grand Prizes that year for designs in glass and wood and for the Finnish Pavilion itself, the cozy earned Sarpaneva a silver medal. It wouldn’t be long before the younger man caught up to his champion.

In 1954, Sarpaneva, left, confers with a craftsman in the Iittala glass factory who is deploying his nontraditional wet-stick method to form one of his most famous works, Orchid. Photo © Kaj Bremer

After two years of experimenting with glassmaking techniques, Sarpaneva pushed the wet-stick method, known since the 19th century, into new territory. Usually glass is blown to form a shape; in contrast, Sarpaneva formed a bubble inside the molten glass, creating the design from the inside out. The show contains several examples of his early wet-stick works, much coveted by collectors today, including Kayak, Lancet and Orchid, which together earned Sarpaneva his first Grand Prize at the Milan Triennial in 1954. By the 1957 edition of the exhibition, he and his countrymen, including Wirkkala, Ahti Nurmesniemi, and Ilmari Tapiovaara, had won so many Grand Prizes, in categories ranging from art glass to textiles, utilitarian glass and architecture, that others grumbled about a Finnish mafia.

Housed in the permanent collection of the Helsinki Art Museum is the 1985 Sarpaneva creation Anakhé. Photo © Rauno Träskelin

“There was no mafia,” Sarpaneva says, laughing, in one of the videos. “In Finland, there was a great yearning for beauty after the war and suffering.” It’s not particularly surprising that designers south of the Alps would be amazed by the amount and diversity of design talent flowing out of Finland, a sparsely populated, barely-industrialized country about which very little was known. In a short memoir written in 2002, Sarpaneva describes childhood visits to his grandparents during the 1930s. “There was an almost total noncash economy,” he recalls. “Everything was made by hand.” People created what they needed, from eating bowls to clothes. The blacksmith bartered with the woodcutter and weaver. Skilled craftsmanship and an appreciation of and respect for useful things was part of everyday life. As Finns started moving from country to town after the war, they brought with them their skills, along with their love and knowledge of finely crafted objects. Their children and grandchildren absorbed that love of craftsmanship, and in the 1950s, some of them applied their skills to creating the warm, sleek, nature-inspired and practical designs that changed the houses and workplaces of Finland and, indeed, the world.

The most breathtaking exhibit in the Helsinki show centers on Sarpaneva’s largest work, Pack Ice, made for Expo 67 in Montreal. The installation on display, at 7 by 30 feet, is only half the size of the original (the remainder is in storage), but it is still a knock out. The long, low table is covered with 210 largely rectangular colorless glass objects. Their surfaces are irregular, the product of an audacious technique invented by the designer. Typically wood molds are soaked in water before molten glass is poured in, with the steam generated protecting the wood from being burned by the intense heat. Sarpaneva eliminated the water, allowing the molds to burn, and the irregularities of the charred surfaces were transferred to the glass. Pack Ice is an ensemble of magical, savage, non-melting ice cubes. It alone is reason enough to visit Helsinki and see this show — but there are many more.