May 3, 2020It’s hard to imagine how one of America’s most ambitious and elaborate gardens — part of a vast and prosperous estate overlooking the Hudson River that in l939 attracted more than 30,000 visitors on a public open day — could have become, within a decade of its owner’s death, abandoned, derelict and almost entirely forgotten.

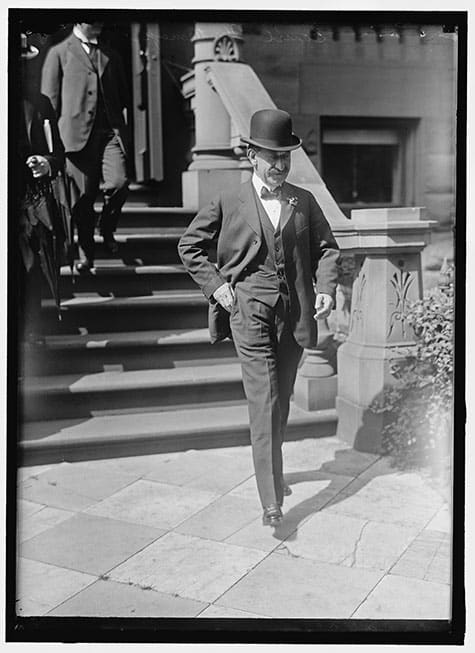

A grim story but one with a happy ending, thanks to a rescue effort that began about 10 years ago. Today, the Untermyer Gardens, once the obsession of Samuel Untermyer (1858–1940), one of the most prominent and affluent lawyers of his day, are not only flourishing again but are the subject of an enthralling new book, Caroline Seebohm’s Paradise on the Hudson (Timber Press). Early chapters focus on the life and career of Untermyer, a self-made man and brilliant lawyer whose clientele included celebrities and movie stars. Reputedly the first attorney to earn a million dollars, he supported women’s suffrage, advocated stock market regulations, proselytized for government ownership of railroads, pressed for reform of the legal system and was much ahead of his contemporaries in understanding the threat posed by Hitler.

The black-and-white photo presents an early view of the walls, canals and circular temple at Greystone; the color photo shows the temple today. Archival photo courtesy of the Hudson River Museum

In 1899, Untermyer bought Greystone, a 113-acre estate across the New York City border in Yonkers, with glorious views of the Hudson and the Palisades. The property, previously owned by Samuel J. Tilden, a former governor of New York, included a 99-room crenellated mansion with seemingly little architectural distinction. (This was demolished in the 1940s.) Untermyer quickly added another 150 acres to his holdings but waited until 1916 to commission William Welles Bosworth, a respected Beaux Arts architect, to make him “the finest garden in the world.” Bosworth was not preeminent in his field, so it may seem strange that the highly competitive Untermyer (who was said to have taken up breeding collies so they would outperform J.P. Morgan’s dog-show winners) hired him. Seebohm suggests that it was because the architect had worked for several years on the design of Kykuit, the Rockefeller estate farther up the river, in Pocantico Hills, laying out a series of terraces and connecting gardens with fountains, installing fanciful pavilions and commissioning classical sculpture.

Some of the 60 gardeners employed by Untermyer, in front of the similarly numerous greenhouses. A 1921 article in the New York Times reported that the lawyer had already spent more than $1 million on his garden Photo courtesy of the Untermyer Gardens Conservancy

Greystone shared with Kykuit amazing views of the Hudson, but unlike the Rockefeller property, it occupied uneven rocky land, which was far from an ideal situation for creating the formal Italianate garden that was then very much the fashion. Bosworth’s challenge was to bend the land to his design and come up with a unifying form for a highly artificial landscape. An added hindrance was having to work around 13 greenhouses that had been installed by Tilden and were beloved by Untermyer, a passionate orchid fancier who experimented with hybridizing plants. “I like to go into the greenhouse with a brush or a rabbit’s foot, carefully transfer pollen from the stamens of one variety of flower to the pistil of another and see what comes of the cross,” he told Better Homes & Gardens.

Bosworth’s solution was to divide the land beyond the greenhouses into six main sections inspired, variously, by Islamic waterways, Mughal architecture, Italianate stairways, Greek columns, classical statuary, ancient mosaics and rock formations — all to spectacular effect.

Architect Stephen Byrns and the Untermyer Gardens Conservancy have brought back large portions of the gardens to showstopping, four-season beauty. Work continues on restoring additional sections.

One of these sections was the Walled Garden. Enclosed on three sides by turreted walls high enough to block any view of the greenhouses and accessed through an austere limestone gate, it featured cruciform canals bordered with low growing perennials. Two magnificent weeping willows flanked the entrance. On the left side were breathtaking views of the Hudson, and in place of a wall, Bosworth designed a circular colonnade with 14 fluted Corinthian marble columns that overlooked a large swimming pool. Later called the Temple of the Sky, the colonnade had a floor decorated with a circular mosaic of Medusa’s head.

To the west of the Walled Garden was the Vista — the design’s most dramatic architectural element, modeled on a flight of stairs at the Villa D’Este in Italy that descends to Lake Como. Its American counterpart is a set of wide steps that cascade hundreds of feet down a steep incline toward the Hudson. At its base is the Overlook, a circular terrace where two ancient Roman marble columns from the estate of architect Stanford White frame river views. From here, a series of terraces and “color” gardens led to a rocky cave set into the hillside. At the landscape’s highest point, a small Temple of Love sat theatrically atop a stupendous rocky promontory from which water coursed down through a series of waterfalls and ponds to the Rock Garden below.

The restored Temple of Love features waterfalls, flowers and other plants.

In its heyday, 60 gardeners worked on the estate tending, according to existing records, 3,200 orchids, 4,000 poinsettias and 58,000 perennials, including roses, dahlias, chrysanthemums, delphiniums and rock plants. A 1921 article in the New York Times reported that Untermyer had already spent more than $1 million on his garden and was said to have laid out over $20,000 one year to import rhododendrons from England. The gardens, open on certain weekdays to the public, extended a more exclusive welcome to some privileged guests, among them composers Franz Schumann and Richard Strauss, who traveled on special trains from Grand Central to attend social functions and musical performances. Much of the silent 1923 film Zawa, in which Gloria Swanson appeared as a torch singer, was shot in the garden.

In 1939, with none of his three children showing any interest in taking over the garden. Untermyer proposed giving it to New York City, which declined the gift. When he died, a year later, no plans for its future had been made. Efforts to bequeath the property to the state, county or municipal government failed because no one, including the heirs, wanted to undertake the cost of keeping it up. Eventually, the City of Yonkers took it over, without any provision for maintaining it. Furniture was sold and statuary dispersed, flowers and shrubs died, lawns and pathways were smothered, and precious mosaics were vandalized. Following decades of decline and neglect, a breakthrough came in 2010 when Stephen Byrns, an architect familiar with the garden who lived nearby, decided to make its reclamation his life’s work. The story of his achievement — the obstacles he overcame, the funding he has raised and the community support he has galvanized — is shared in fascinating detail in Seebohm’s book.

Today, restoration continues apace, and seven gardeners are at work on the property. Land has been cleared, canals drained and cleaned, deer fencing installed, the Walled Garden brought back to life and the Vista cleaned up and replanted. The Temple of Love and the rock garden below are again in good shape. More work is underway, and the progress is visible to regular visitors, whose numbers now reach more than 75,000 every year (because of the coronavirus pandemic, the site is currently closed). It’s a garden on the move and a feel-good story that Samuel Untermyer would surely applaud.