March 20, 2013Dempsey and Firpo, 1924, by the early-20th-century realist George Bellows. The painter is the subject of a traveling exhibition currently on view at London’s Royal Academy of Arts through June 9. Image © Sheldan C. Collins/The Whitney Museum of American Art

George Bellows captured New York and our young, multiethnic, rapidly urbanizing nation at a formative moment: the first two decades of the 1900s. His iconic scenes, made primarily between 1904 and 1912, of boxing bouts, tenements, shipyards, river squatters and NYC’s diverse mean streets won the painter, illustrator and printmaker a place among America’s premier social realists.

Bellows was a Midwesterner and attended Ohio State, anticipating a sit-at-your-desk career in commercial illustration (the only work for artists in that time and place). But a broader vision of art, and his place in it, took him to New York, where he joined Robert Henri’s loosely formed Ash Can School — a name that announced the group’s quickly observed, raw street themes. Bellows blossomed under Henri’s reportorial studio style and his theory that art must take in its world without edits, elitism or reservation.

Bellows is now the subject of a comprehensive traveling exhibition, perhaps the largest, most in-depth survey of the artist’s work in more than 30 years. And while previous shows focused on either his canvases or his graphic work, this one — called “Modern American Life” and comprising some 130 paintings, drawings and lithographs — looks closely at all mediums and both his early and late work. The exhibit debuted to record crowds at Washington, D.C.’s National Gallery of Art last summer before moving to New York’s Metropolitan Museum in the fall. Its final run began on Saturday at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, and runs through June 9. Here, Charles Brock, an associate curator in the department of American and British paintings at the National Gallery who oversaw the show’s planning, talks to Introspective’s Marlena Donahue about the artist’s life, legacy and work.

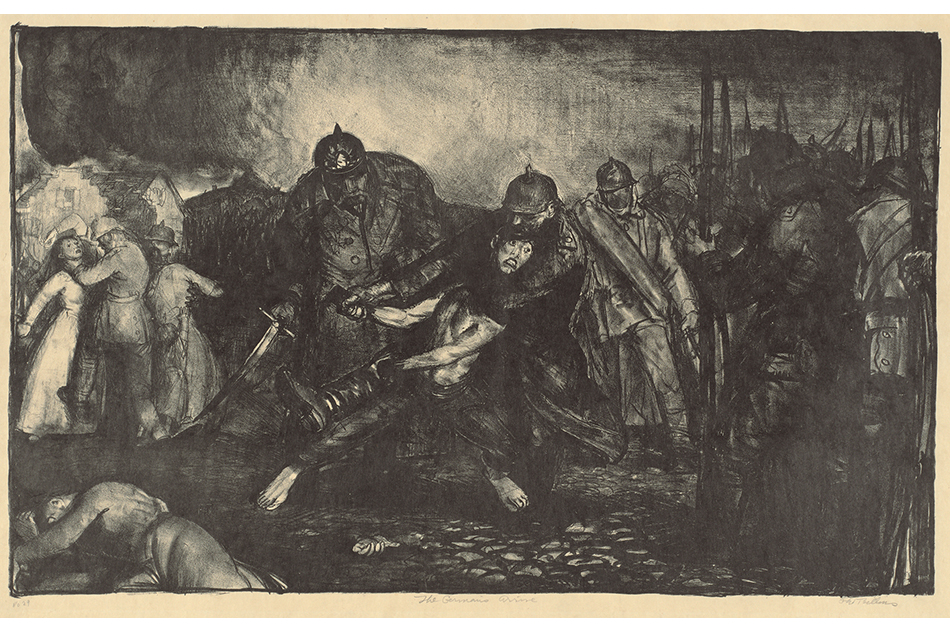

Billy Sunday and the Sawdust Trail, 1915

Is Bellows still relevant?

I have to say that the response to Bellows at the National Gallery was amazing. We had 230,000 people go through, and I have never given so many tours for an exhibition.

In our very eclectic and fast-paced current art scene, what makes an early-2oth-century American realist relevant?

Since the National Gallery of Art opened in 1941, George Bellows has formed a substantial core of the gallery’s American art collection. He is a defining artist in our country’s history and art history.

Given The National Gallery’s tight connection with Bellows, is it safe to assume the show’s contents come mainly from your institution?

No, there are some 60 wonderful private collectors who lent standout works, though they asked that their names be de-emphasized.

Paddy Flannigan, 1908. Courtesy of Erving and Joyce Wolf

Can you give a few examples?

River Rats and the really famous Paddy Flannigan.

Paddy Flannigan shows a bare-chested, scrappy street urchin caught on the fly, with loose, sketchy strokes of deep red under the paint, which is just a bit disturbing.

Yes. And when seen with all the other works, you see the richness of Bellows’s curiosity. He moved from one medium to another, testing ideas in prints that were worked out on canvases or vice versa; you see him moving from one theme to another, mixing themes and moving along very selectively only when he had investigated every aspect of a subject or a method.

Can you be a bit more specific?

Well, take the theme of boxing for example. For the first time under one roof we can see the stunning Stag at Sharkey’s, from 1909, lent by the Cleveland Museum of Art, next to the Whitney Museum’s very famous Dempsey and Firpo of 1924, plus several works from the National Gallery, including Club Night, 1907, and 1909’s Both Members of This Club. You begin to grasp the variety, experiments and depth within subjects we know and across subjects we are less familiar with.

“Art was art to Bellows, and he was a humanist as much as he was an American.”

Both Members of This Club, 1909. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art

Is Bellows’s significance partly historical, that he saves for posterity ways of dressing, being, moving before personal cameras and iPhones could do the same?

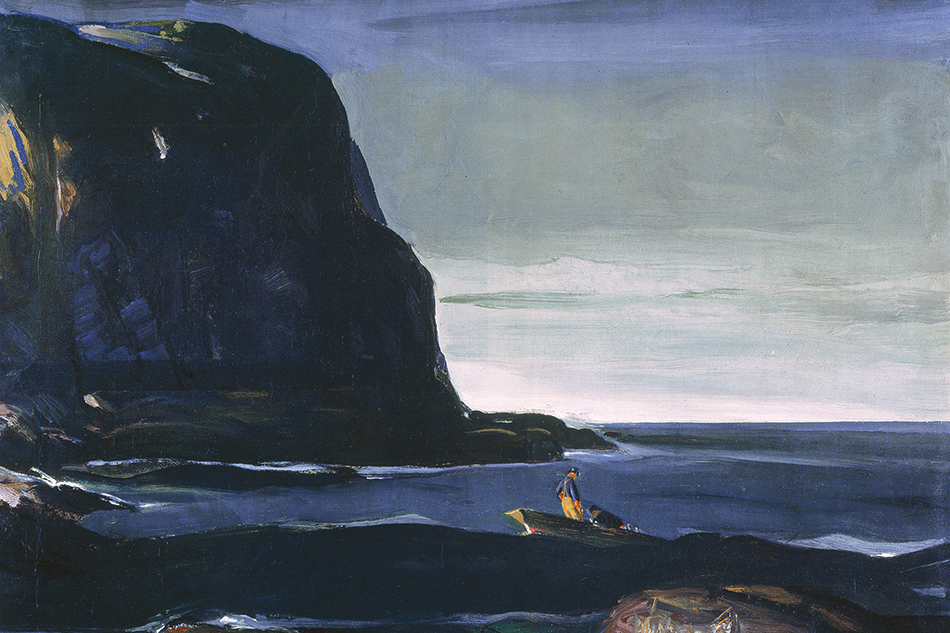

There is so much more going on than that. Take the work called The Lone Tenement from 1909, where we see this large, almost abstract square of building captured in a way that suggests a structure both there and not quite there. He concentrates our eye more on a vast abstract space left by the leveling of buildings, not on a building, per se.

It was a swath of New York being cleared to build skyscrapers, like a harbinger of gentrification.

Bellows was not a political artist, but here it seems he is ever-so-subtly pondering for himself and us where the poor who lived in those low-income houses would go as Manhattan urbanized.

His realism is very complex and subtle, like the light and dark skinned boxers going blow-for-blow in Both Members of This Club. It’s almost as if he’s saying that out in the world of commerce and class there are gross inequities, but in the ring, on the riverbanks, at war, men are measured for themselves — a little naïve and sexist maybe, but as social comments go, pretty profound for his day.

Exactly. In the Dempsey vs. Firpo canvas, Bellows chooses the indecisive moment but does not soft touch the violence. He shows us the moment when Firpo knocked Dempsey out — and we know Dempsey gets up and wins the fight. There is always something interesting, personal to his view and a way that makes us stay there, forces us to look, think and take stock of what he is doing and how he is saying it.

Madeline Davis, 1914. Courtesy of Lowell and Sandra Mintz

We always read that Bellows, like his teacher Robert Henri, mounted an intentional assault on academic painting.

I have to disagree. Henri traveled to Europe and was very aware and respectful of the academic tradition, as well as fascinated with ideas of modernity; he communicated and taught these ideas to students like Bellows. Both artists were versed in the whole tradition of Western art, particularly academic realists like Frans Hals, Velázquez, Goya and also Manet.

Then there’s the view that his art was a maverick, all-American retort to prissy Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Symbolism, Cubism and the whole idea that old Europe meant new culture.

Bellows was deeply aware of and steeped in modernity, all its abstract, formal and social ideas. He and Henri were very responsive to Impressionism and Post-Impressionism — don’t forget that Stieglitz opened his modernist Gallery 291 in New York around this time, and it was a hub for Bellows and other vanguard thinkers.

He was, however, at the end of the day, an American-scene realist, and we tend to either love him or hate him on that score.

Bellows would not like one bit this idea that art stands for a nationality; art was art to Bellows, and he was a humanist as much as he was an American.

Counted Out, No. 1, 1921. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art

And what about this idea that his heyday ends in 1913 with a terrible reaction to the Armory show’s display that year of vanguard works from Europe, after which he is said to have declined into commercial prints?

That statement overlooks the simple fact that he was a prodigy. He comes to New York in 1904 and only two years later has painted River Rats and Stag at Sharkey’s — two major and undisputedly advanced works, according to everyone.

So did he lose his edge?

That kind of talent does not just go away. An overview like this reveals that fact. Artists have to eat, and if you were not making portraits of the rich, you did not make a ton of money, even when you were as famous as Bellows was by 1912. He made prints to sell art and in the process used the graphic work for thinking.

Are the critics that don’t see him clearly today not looking closely?

Let’s just say he was able to amplify the inevitable tensions between observation and commentary, between figuration and abstraction, the American and the human, and these ambiguities don’t produce easy handles for art reviews, but they do underlie most great art.